Algorithms for Approximate String Matching - Alignment

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Preface & References

I document topics I’ve discovered and my exploration of these topics while following the course, Algorithms for DNA Sequencing, by John Hopkins University on Coursera. The course is taken by two instructors Ben Langmead and Jacob Pritt.

We will study the fundamental ideas, techniques, and data structures needed to analyze DNA sequencing data. In order to put these and related concepts into practice, we will combine what we learn with our programming expertise. Real genome sequences and real sequencing data will be used in our study. We will use Boyer-Moore to enhance naïve precise matching. We then learn indexing, preprocessing, grouping and ordering in indexing, K-mers, k-mer indices and to solve the approximate matching problem. Finally, we will discuss solving the alignment problem and explore interesting topics such as De Brujin Graphs, Eulerian walks and the Shortest common super-string problem.

Along the way, I document content I’ve read about while exploring related topics such as suffix string structures and relations to my research work on the STAR aligner.

Algorithms for Approximate Matching

As we saw previously, due to sequencing errors and the fact that while another genome of the same species might have a $99\%+$ but not perfect match with the genome we’re reconstructing, the reads we are trying to sequence together might suffer severely if we simply attempt exact matching. Here we rely on techniques of approximate matching to tell us where these short reads might fit together in the final puzzle.

Levenshtein Edit Distance is a string metric which is used to quantify how different two strings (such as words) are from one another. It is calculated by calculating the smallest number of operations needed to change one string into the other. These operations are very similar to operations which might happen in real DNA which causes these changes. Substitution could be the errors in sequencing, insertions and deletions along with substitutions could model gene-splicing and related operations.

Global Alignment

The Levenshtein Edit Distance is what we use to solve the global alignment problem in DNA sequencing. Global alignment is pretty much equivalent to the edit distance problem, except for a minor change in the scoring system which we’ll discuss at the end of this section. If we define a function $F$ to be the edit distance between two strings.

Local Alignment

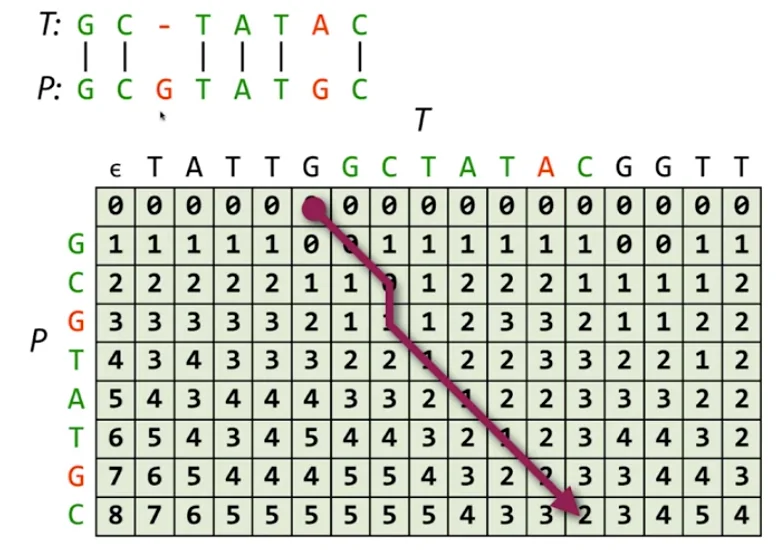

Local alignment is similar, but instead of searching for the match score between two sub-sequences, it is more suited to working with short reads in a bigger sequence. That is, it is good at finding positions in a bigger text where a smaller pattern could’ve occurred using approximate matching. This is pretty similar to our exact pattern finding algorithms except that it is more versatile in how it detects its matches and assigns them scores instead of binary exact matching. The recurrence here is pretty simple, we use the same global alignment recurrence except we change one of the base cases to:

$$F(0, j) = 0$$

This lets us solve the local alignment problem in the same time complexity as global alignment.

The Scoring Matrix

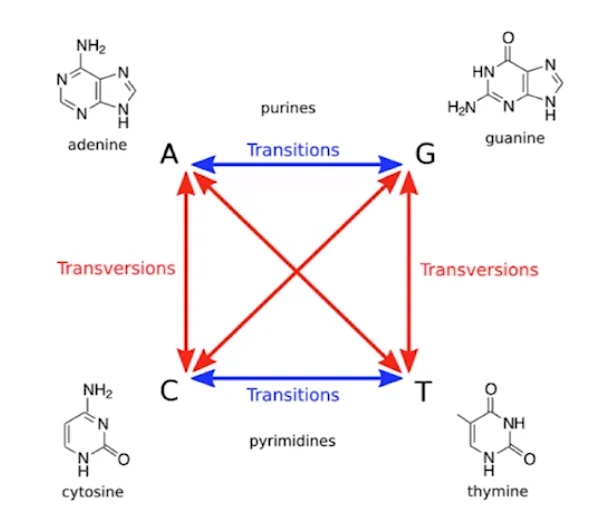

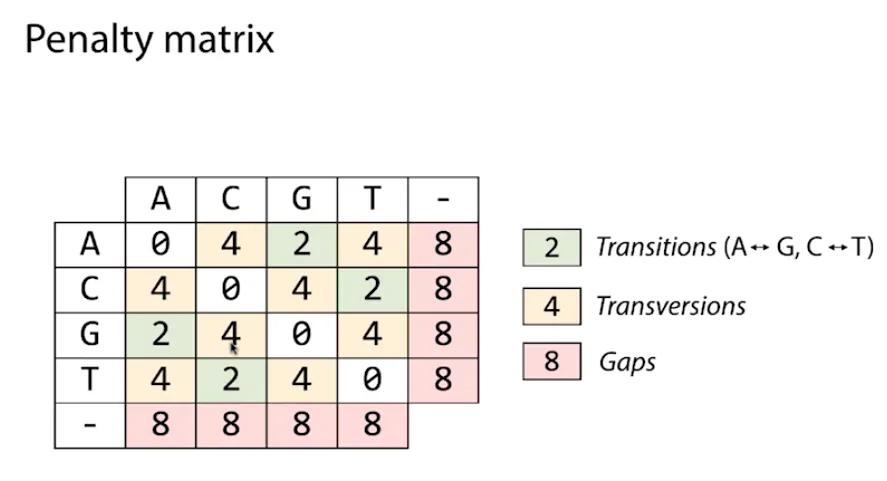

For edit distance, the scoring is pretty much just $\pm1$ for all operations. For DNA sequences however, take the example of the human genome:

Simply listing the possibilities reveals that there are twice as many different types of transversion as there are different types of transitions. We may thus assume that transversions will occur twice as frequently as transitions. However, it turns out that transversions are only slightly more common than transitions when we look at the replacements that separate the genomes of two unrelated individuals. So, contrary to what we may think, it is the opposite way around. Therefore, we should penalize transgressions more severely than transitions in our penalty system. Further, indels are less frequent than substitutions. So we might want to penalize indels more than substitutions. So we modify our scoring matrix to reflect these real world statistics in practice.

Combining Both Approximate and Exact Matching

It seems like approximate matching is the solution we’ve been waiting for and a useful tool that will give us good matches for placing our short reads and thus help us reconstruct the sequence. This is true, but the problem herein lies in the fact that the approximate matching algorithms, while versatile, are much slower than their exact matching counterparts. While most of the exact matching algorithms run in linear or with an extra logarithmic factor, the approximate matching algorithms run in quadratic time and are usually also hard to vectorize or speed-up due to the dependency between their states.

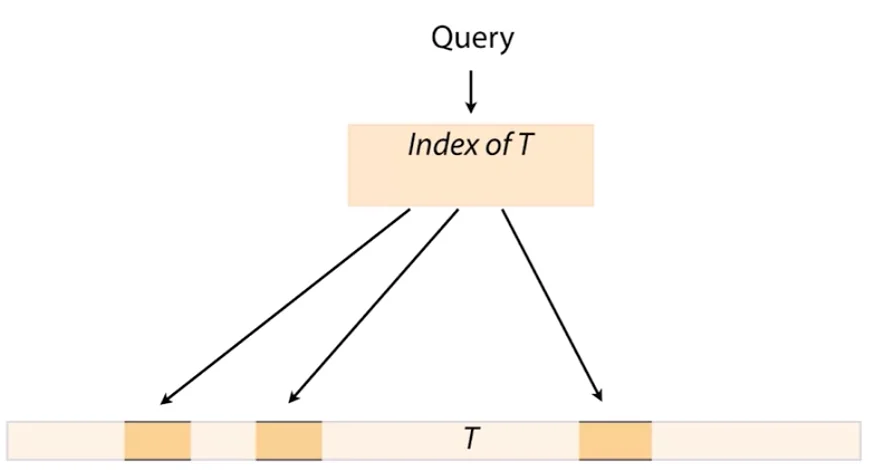

If we simply ran local alignment between each of the short reads (which we usually have a billion or so off) and the human genome (which is also a billion characters in length), the computational task is infeasible for even today’s most powerful compute nodes to solve quickly. Therefore we have to come up with a match of both approximate and exact matching algorithms to solve the overall problem quicker. Exact matching (Booyer-Moore & Knuth-Morris-Pratt for Exact Matching) is useful in pinpointing a few specific locations where we can then go and run approximate matching algorithms on. Consider the following figure:

We begin by querying the k-mer index table for a query which allows us to rapidly home in on small set of candidate needles which are the only places in the entire sequence we really need to run our powerful but slower approximate matching algorithms on.

Thus, both concepts work well together, kind of making up for each other’s shortcomings while still accomplishing their goals. On the one side, the index is highly quick and effective at reducing the number of locations to check, but it completely lacks a natural way to manage mismatches and gaps. However, dynamic programming does handle inconsistencies and gaps rather nicely. But it would be incredibly slow if we simply used dynamic programming.