Are There Computational Problems That Computers Cannot Solve?

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Are there computational problems that computers cannot solve? How do we find the answer to this question? Turns out there’s a very simple way to answer this question, even without defining what an “algorithm” is (Church-Turing Hypothesis).

Notice that if we are able to prove that there are uncountable many computational problems and only countably many computer programs. Then this would imply that there must exist uncountable many problems for which, no computational program solution exists.

🧮 Countable sets An infinite set is countable if there is a bijection $f:N\to S$ from natural numbers to S Uncountable sets An infinite set is countable if it is not possible to construct a bijection $f:N\to S$ from natural numbers to S. A common proof method is cantor’s diagonalization which first assumes that it is possible to construct such a bijection and then proves that for every such bijection, we can always create a new element in the set that was not mapped before. Thus disproving that any such bijection can be created.

Proving that the set of all programs is countable

Now, notice that every single program that we write, must be encoded to some subset in the set of all finite-length bit strings, i.e., some subset of $\{ 0, 1 \}^*$. We can draw an analogy here to how every compiled C program, for example, has its own unique binary file which can be used to represent it as a finite-length bit string.

Theoretically, it is true that every possible program that we can write can be uniquely encoded as some finite-length binary string. We also know that the subset of an infinite countable set must be countable. Therefore, it suffices to prove that the set $\{ 0, 1 \}^*$ is countably infinite for the first part of our proof.

Every finite length binary string is just a natural number encoded in binary. This allows us to uniquely map such a bijection from the natural numbers to the set $\{0,1\}^*$.

$0\to0, 1\to1, 10\to2, 11\to3, 100\to4 \ \dots$

This implies that the set of all finite-length binary strings $\{ 0, 1 \}^*$ must be countably infinite. Therefore, since the set of all finite-length programs is a subset of this set, it must also be countable.

Proving that the set of all computational problems is uncountably infinite

Let us prove that $P( \{0, 1\}^*)$, i.e., the power set of all finite-length bit strings is uncountable. Notice that every problem is modeled as a decision problem. And every decision problem is characterized by a set. Or it’s “language.” Therefore, every possible subset of the set of all finite-length binary strings, actually represents a problem. Each subset is a unique language and each of them characterizes unique problems.

Therefore, counting the total number of computational problems essentially reduces to calculating the cardinality of the power set $P(\{0, 1\}^*)$

Consider the following function $f:\{0, 1\}^*\to\{0, 1\}$ which maps the set of all finite-length binary strings to a subset. Let us pick some subset $S \subset \{0, 1\}^*$. Then the function is defined as follows:

$$ f(x)= \begin{cases} 1 \ \forall \ x \in S \ 0 \ \forall \ x \notin S \

\end{cases} $$

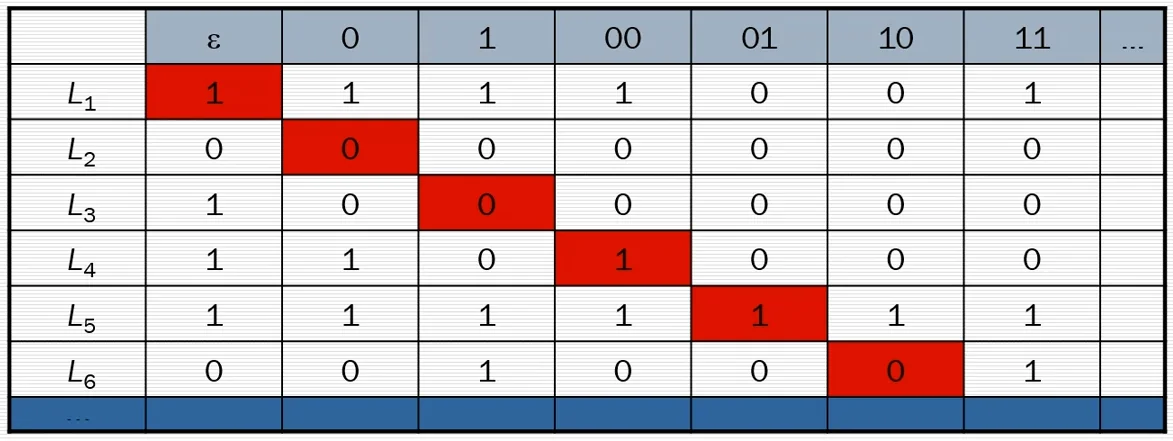

Now let us calculate $f(x)$ for every such language and write it in the form of a table

Let us assume that we have enumerated an infinite number of such languages. Now we will use diagonalization to prove that there will always exist some language $L_x$ that does not belong to our set.

We construct $L_x$ as follows. We move along the diagonal and flip the value of $L_i$ for each element $i$ of the set.

$L_x(\epsilon) = 0, L_x(0) = 1, L_x(1) = 1, L_x(00) = 0, L_x(01) = 0 \ \dots$

We notice that such a language $L_x$ does not belong to the set as it differs from each $L_i$ belonging to our bijection at the $i^{th}$ element. This means we have successfully proved the existence of a language that does not belong to our bijection. No matter how many times we repeat the process of finding such a language and adding it to the bijection, we will always be able to prove the existence of such a new language that does not belong to the bijection. Hence we have proved that the power set $P(\{0, 1\}^*)$ is indeed, uncountably infinite.

This implies that the cardinality of the set of all computational problems is greater than the set of all possible computer programs. This in turn implies that there are uncountably many computational problems that we cannot find computational solutions for.

That is sad. But we might still hope that most of these computational problems that we cannot solve are also problems that we are not interested in solving. This is, however, not true. Consider the following problem,

Program equivalence problem

Definition: Write a program that takes two programs as input and checks whether both the programs solve the same problem.

We will prove this in further lectures, but for the sake of intuition, notice that there are many many different ways to program an algorithm to solve a particular computational problem. It is not intuitively possible for us to write a program that can take two finite-length bit strings and deterministically say whether they both solve the same problem.

This is a useful program as it allows us to check the accuracy of programs easily. However, since this is not a problem we can solve, we have resorted to probabilistic solutions which test two programs by running them on a large collection of sample test cases and checking if their outputs are the same. However, note that this is a probabilistic solution and not a deterministic solution.

References

These notes are old and I did not rigorously horde references back then. If some part of this content is your’s or you know where it’s from then do reach out to me and I’ll update it.

- Professor Kannan Srinathan’s course on Algorithm Analysis & Design in IIIT-H