Building a Type-Safe Tool Framework for LLMs in Scala

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Tool Calling

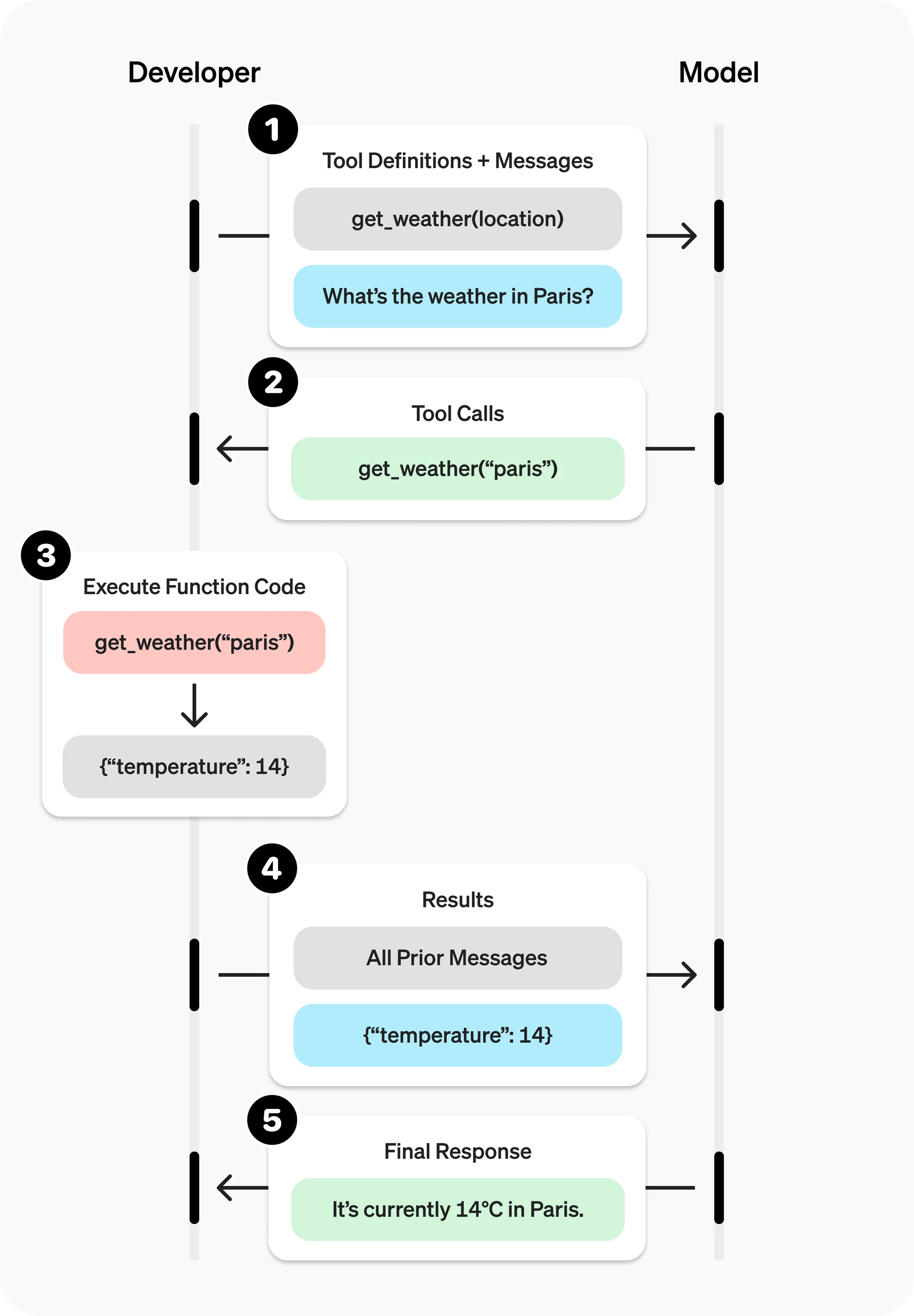

I came across a fun problem at work today where I wanted to define a clean, idiomatic way to define functions in Scala and auto-generate the function schema for these functions to pass to LLM APIs. For some context, LLMs are incredibly powerful at reasoning through and generating text, but to really have them interact with the environment, they use external tool calling. OpenAI calls this Function Calling and Anthropic calls it Tool Use. This image from OpenAI best summarizes the idea:

You as a developer pass in function schemas to let the LLM know that it has access to call xyz function. The schema may look like this:

{

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_weather",

"description": "Retrieves current weather for the given location.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "City and country e.g. Bogotá, Colombia"

},

"units": {

"type": "string",

"enum": [

"celsius",

"fahrenheit"

],

"description": "Units the temperature will be returned in."

}

},

"required": [

"location"

],

"additionalProperties": false

},

"strict": true

}

}

Here, you’re telling the LLM that it has access to a get_weather function which retrieves the current weather for a given location. Further, you let it know that this function takes in two arguments:

location: string=> The argumentlocation, of typestring. This is the city and country the LLM is trying to get the current weather for.units: "celsius" | "fahrenheit"=> The argumentunits, which is an enum that can either be"celsius"or"fahrenheit".

You also define that location is a required argument, units is not. It’s more or less equivalent to a precise documentation of an API that a human would read to understand how to call said API. In the past, you would prompt the LLM with non-standard structured schema and ask the LLM to output JSON making the tool call. You would then parse out this JSON block manually and make the tool call. We’ve not evolved much from there, but modern LLM APIs have “solved” this elegantly by handling this prompt-engineering + fine-tuning + parsing logic on their end. It’s a little more than glorified prompt engineering, there are techniques which can guarantee that a model’s output will be a JSON object that adheres to a specified JSON schema as long as enough tokens to complete the JSON object are generated. This, along with some fine-tuning masked on the API provider side gives you a clean API that you can use to allow the model to perform tool calls.

Under the hood, constrained decoding powers structured outputs. Constrained decoding is a technique in which we limit the set of tokens that can be returned by a model at each step of token generation based on an expected structural format. For example, let’s consider the beginning of a JSON object which always begins with a left curly bracket. Since only one initial character is possible, we constrain generation to only consider tokens that start with a left curly bracket when applying token sampling. Although this is a simple example, this example can be applied to other structural components of a JSON object such as required keys that the model knows to expect or the type of a specific key-value pair. At each position in the output, a set of tokens adherent to the schema are identified, and sampled accordingly. More technically, raw logits output by the LLM that do not correspond to the schema are masked at each time stamp before they are sampled.

Okay, the LLM understands the schema and we can force it to output JSON objects constrained to a specific JSON schema, what’s next? In the previous example, the LLM would see this schema and know it can call get_current_weather with a location and unit. When it decides to use the tool, it generates something like:

[

{

"id": "call_12345xyz",

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_weather",

"arguments": "{\"location\":\"Paris, France\"}"

}

},

...

]

The API caller would then go through this list of tool calls the LLM has requested and execute them one-by-one (or in parallel). The LLM only speaks text, so the outputs of all these function / tool calls will be read by the LLM as strings. The outputs can themselves be structured or semi-structured, it’ll be processed as is by the LLM. The API caller would then add a message to the prompt similar to:

{

"role": "user",

"content": [

{

"type": "tool_result",

"tool_use_id": "call_12345xyz",

"content": "65 degrees"

}

]

}

The LLM can then use this information and reply back with something like “The current weather in Paris is 65 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s a cool day in the city of love!”

This API is pretty neat and covers up a lot of the complexity involved in making the LLM outputs constrained to a fixed schema. The next challenge, then, is to determine how best to expose this capability in a clean, idiomatic, and developer-friendly way within a given programming language—in my case, Scala—ideally by treating tool schemas and invocations as first-class constructs expressible through the language’s type system, implicits, and meta-programming capabilities. We want the usage to ensure type-safety but also allow semantically rich integration with the LLM API.

The Challenge: Making This Developer-Friendly

Manually writing these JSON schemas is obviously a bad idea. It’s tedious, there’s no type-safety and we’re likely to have errors. There’s two sources of truth which have to constantly be kept in sync. This won’t do. We need a clean way to be able to generate the function schema from a function definition. Write the tool once, modify it how many ever times you want to and the framework should automatically be capable of generating everything else.

Python

This is actually achieved pretty easily in Python, thanks to libraries like Pydantic and typing:

from typing import Annotated, Literal, Optional, get_type_hints

import json

def param(description: str, required: bool = True):

return {"description": description, "required": required}

def get_weather(

location: Annotated[str, param("City and country e.g. Bogotá, Colombia")],

units: Annotated[Optional[Literal["celsius", "fahrenheit"]],

param("Units the temperature will be returned in.", required=False)] = "celsius"

) -> str:

"""Retrieves current weather for the given location."""

return f"65 degrees {units} in {location}"

def generate_function_schema(func):

hints = get_type_hints(func, include_extras=True)

properties = {}

required = []

for name, hint in hints.items():

if hasattr(hint, '__metadata__'):

meta = hint.__metadata__[0]

properties[name] = {

"type": "string",

"description": meta["description"]

}

if meta.get("required", True):

required.append(name)

return {

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": func.__name__,

"description": func.__doc__,

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": properties,

"required": required

}

}

}

schema = generate_function_schema(get_weather)

print(json.dumps(schema, indent=2))

The output looks something like:

{

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_weather",

"description": "Retrieves current weather for the given location.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "City and country e.g. Bogot\u00e1, Colombia"

},

"units": {

"type": "string",

"description": "Units the temperature will be returned in."

}

},

"required": [

"location"

]

}

}

}

Python has support for powerful meta-programming features which makes this possible. The typing module let’s you inspect the type signatures of live objects during runtime and the meta-programming friendly double underscore attributes makes fetching the function name, it’s doc string and annotations super easy. Adding to the above, if we use Pydantic and define the attributes in a class, we can call it’s model_json_schema() library function to handle a lot of the schema construction tedious logic. One of the many reasons why Python is super popular in the LLM / Agent framework community.

CPP

I’d love to try this in C++ next, I’m sure you could craft some beautifully convoluted template and pre-processor magic to make it happen, but I’m skipping it in the interest of my sanity and time. JSON in C++ shudders. (Mental note to revisit this later, because who doesn’t enjoy a little masochism?)

Scala 2

Let’s start by defining some kind of target end-state we want to expose to developers using our framework. This would be perfect,

@Tool(

name = "get_weather",

description = "Retrieves current weather for the given location."

)

def getWeather(

@Param(

description = "City and country e.g. Bogotá, Colombia",

required = true

)

location: String,

@Param(

description = "Units the temperature will be returned in.",

enum = Array("celsius", "fahrenheit"),

required = false

)

units: String = "celsius"

): String = ???

Spoiler, I’ll fail to get this to work. We’ll actually end up with something more like:

object TemperatureUnit extends Enumeration {

type TemperatureUnit = Value

val CELSIUS, FAHRENHEIT = Value

}

case class WeatherArgs(

@Parameter(description = "The city and state, e.g., Bangalore, IN")

location: String,

@Parameter(description = "The unit for the temperature")

unit: Option[TemperatureUnit.Value] = None

)

@Tool(name = "get_current_weather", description = "Get the current weather in a given location")

class WeatherTool extends ToolExecutor[WeatherArgs] {

def execute(args: WeatherArgs): String = {

s"The weather in ${args.location} is 72 degrees ${args.unit.getOrElse(TemperatureUnit.FAHRENHEIT)}."

}

}

Slightly less “nice”, but it’s actually almost exactly the same interface Pydantic uses to automate function schema generation!

But anyways, let’s try to implement the initial interface we described. Annotations seem easy enough to tack-on later, let’s tackle the main problem, how do we fetch the type signatures of the function arguments and generate the schema for it? You can either do this at compile time, or during runtime. Scala 2 makes this choice simple for me, it does not have first class support for compile time meta-programming. ChatGPT tells me Scala 3 has support, but I’m locked to Scala 2, so oh well. How do I get the type information of a variable at runtime then?

Problem 1: Type Erasure

Here we’ll hit our first (and probably biggest) obstacle. At runtime, the JVM does not hold onto any type information for generics.

class Container[T](value: T)

val stringContainer = new Container[String]("hello")

At runtime, the JVM doesn’t know that stringContainer holds a String. The type parameter T is erased during compilation (WHY?!). This leads to you observing fun behavior, like this:

val strings: List[String] = List("a", "b", "c")

val ints: List[Int] = List(1, 2, 3)

println(strings.getClass) // class scala.collection.immutable.$colon$colon

println(ints.getClass) // class scala.collection.immutable.$colon$colon

println(strings.getClass == ints.getClass) // true

This is why statically typed languages are far superior… However, even in comparison to dynamically typed languages like Python, type information is usually maintained as a piece of runtime data instead of just being erased.

Note: The JVM only erases generic type parameters, not the actual types of objects.

WHY?!

So the natural question: why would a dynamically typed language deliberately erase useful type information at runtime? As expected, there’s a brilliant reason for it…

Java trying to monkey patch a new feature (Generics) onto an existing mess of a language. Co-incidentally, great video, should watch.

The short version is that, the designers needed old code (pre-generics) to run on the new JVMs without recompilation and for the new-generic code to be callable from the old non-generic code. This way, the bytecode format can be unified and will work everywhere. Here’s an example:

// Pre-Generics Java

List oldList = new ArrayList();

oldList.add("string");

oldList.add(42); // This works

// Post-Generics Java

List<String> newList = new ArrayList<String>();

These two snippets should both compile to identical bytecode for the format to be unified and not require recompilation. The only way to do this is to erase the generic type information.

How does this even work?

A follow up question you may have is how does the JVM still work if types are erased for generics? How does it do method dispatch for example? Let’s go back to the stringContainer example:

class Container[T](value: T)

val stringContainer = new Container[String]("hello")

// --- After type eraseure ---

class Container(value: Object) { // T becomes Object

def getValue: Object = value

def func(): Unit = ???

}

// The compiler can just cast it here implicitly since when fetching an object, it's implicit type should be known at compile time

// thanks to generics allowing for stronger static typing guarantees... ironically.

val stringContainer = new Container("hello")

val str: String = stringContainer.getValue.asInstanceOf[String]

So in essence, because generics provide a lot of static type-safety guarantees at compile time, the compiler can (at compile time) insert these casts to correctly cast all generic field accesses. But this also means that at runtime, we as the developer can’t easily ask “what type was this generic parameter?”

Solution

So, we can’t “easily” fetch the type of a generic at runtime, but how do we do it? Short answer, Reflection. Long answer…

Reflection

Reflection is the ability of a program to inspect, and possibly even modify itself. It has a long history across object-oriented, functional, and logic programming paradigms. While some languages are built around reflection as a guiding principle, many languages progressively evolve their reflection abilities over time.

Reflection involves the ability to reify (i.e. make explicit) otherwise-implicit elements of a program. These elements can be either static program elements like classes, methods, or expressions, or dynamic elements like the current continuation or execution events such as method invocations and field accesses.

Reflection can be divided into two broad groups depending on what phase of the code development loop it runs in.

- Compile-time Reflection: can be considered a superset of templates in C++. All the introspection, inspection and instantiation of code is done at compile time. These patterns are very powerful for developing generic containers and algorithms to perform transformation & reductions on these containers.

- Runtime Reflection: gives access to the program to inspect it’s own type metadata and even modify it during program execution. This is powerful, but also dangerous. It lets us bypass all compiler placed safety nets like allowing users to modify

constvariables, accessprivatemembers of classes and cause more chances to throw errors during execution. This is sometimes useful to allow easier mocking ofprivatemethods of classes in unit-tests, easier dependency injection & other serialization / de-serialization problems where you may want to map Java/Scala types to a standard schema like JSON, Proto, Database rows, etc.

In short, a language uses “Reflection” to provide you hooks to inspect, instantiate, modify or invoke members of that object

TypeTag

Scala’s types being erased at runtime essentially means that there is information that is available at compile time that is erased / lost during runtime. The classic Java solution to this problem seems to be tacking on another monkey patch to allow developers to “persist” this information using TypeTags. TypeTags are generated by the compiler. Here’s some example usage.

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe._

// The [T] is defining a generic method. It's a type parameter like in C++ templates and Scala will substitute it in.

// We're currying the implicit argument here. It's the same as

// def inspectTypeWithTag = (value: T) => (tag: TypeTag[T]) => Unit.

// Scala just fills in the implicit argument automatically.

//

// So when this function is called with say `inspectTypeWithTag("a")`, Scala does 2 things:

// 1. Infer T = List[String].

// 2. Search for an implicit TypeTag[List[String]] in scope and pass it in.

def inspectTypeWithTag[T](value: T)(implicit tag: TypeTag[T]): Unit = {

println("=== With TypeTag ===")

println(s"Runtime class: ${value.getClass}")

println(s"Static type: ${tag.tpe}")

println(s"Type constructor: ${tag.tpe.typeConstructor}")

println(s"Type arguments: ${tag.tpe.typeArgs}")

}

def inspectTypeNoTag[T](value: T): Unit = {

println("=== Without TypeTag ===")

println(s"Runtime class: ${value.getClass}")

}

val list = List("a", "b")

inspectTypeNoTag(list)

inspectTypeWithTag(list)

/* === Without TypeTag ===

Runtime class: class scala.collection.immutable.$colon$colon

=== With TypeTag ===

Runtime class: class scala.collection.immutable.$colon$colon

Static type: List[String]

Type constructor: List

Type arguments: List(String) */

The TypeTag is like a persisted metadata blob containing all the type signature info of the object at compile time, before erasure ate it.

Reflection (cont…)

What’s an “Universe”?

The reflection environment differs based on whether the reflective task is to be done at run time or at compile time. The distinction between an environment to be used at run time or compile time is encapsulated in a so-called universe. Another important aspect of the reflective environment is the set of entities that we have reflective access to. This set of entities is determined by a so-called mirror.

For example, the entities accessible through runtime reflection are made available by a

ClassloaderMirror. This mirror provides only access to entities (packages, types, and members) loaded by a specific classloader.Mirrors not only determine the set of entities that can be accessed reflectively. They also provide reflective operations to be performed on those entities. For example, in runtime reflection an invoker mirror can be used to invoke a method or constructor of a class.

There are two principal types of universes– since there exists both runtime and compile-time reflection capabilities, one must use the universe that corresponds to whatever the task is at hand. Either:

scala.reflect.runtime.universefor runtime reflection, or

scala.reflect.macros.Universefor compile-time reflection.A universe provides an interface to all the principal concepts used in reflection, such as

Types,Trees, andAnnotations.

What’s a “Mirror”?

All information provided by reflection is made accessible through mirrors. Depending on the type of information to be obtained, or the reflective action to be taken, different flavors of mirrors must be used. Classloader mirrors can be used to obtain representations of types and members. From a classloader mirror, it’s possible to obtain more specialized invoker mirrors (the most commonly-used mirrors), which implement reflective invocations, such as method or constructor calls and field accesses.

In short, the JVM exposes APIs to get access to the class information, accessible fields / methods, etc. Mirrors are an abstraction on top of these JVM APIs in Scala that knows how to call these underlying JVM APIs to perform reflection operations on Scala classes. Universes just group these mirrors into runtime / compile time reflection operations. Let’s take this simple Person class for illustration:

case class Person(name: String, age: Int)

val alice = Person("Alice", 30)

Now let’s access the name field using both approaches:

1. Raw Java Reflection:

val personClass = alice.getClass

val nameField = personClass.getDeclaredField("name")

nameField.setAccessible(true)

val value = nameField.get(alice)

println(s"Java reflection result: $value") // "Alice"

2. Scala Reflection:

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe._

import scala.reflect.runtime.currentMirror

// val personType: reflect.runtime.universe.Type = Person

val personType = typeOf[Person]

// val nameSymbol: reflect.runtime.universe.TermSymbol = value name

// It's basically an internal representation of the identifier "name". In Scala reflection, names of members (like fields or methods) can be either:

// - TermName for values, variables, methods, and objects

// - TypeName for type members, type aliases, and classes/traits

val nameSymbol = personType.decl(TermName("name")).asTerm

// Create mirrors

val instanceMirror = currentMirror.reflect(alice)

val fieldMirror = instanceMirror.reflectField(nameSymbol)

// Access the field

val value = fieldMirror.get

println(s"Scala reflection result: $value") // "Alice"

When you call fieldMirror.get, Scala internally calls the Java reflection APIs exposed by the JVM. The mirrors are just a more elegant, type-safe wrapper around java.lang.reflect.* APIs.

Problem 2: Limited Runtime Reflection

While Scala provides runtime reflection through its reflection API, it’s not as straightforward as Python’s __annotations__ or sig. We still need to implicitly layer in a TypeTag so that we can capture type information under-the-hood without exposing the developer to weird APIs and also come up with a substitute for things like __doc__ in Python. We can use Annotations in Scala for this. In Python, decorators are just functions that transform other functions. In Scala, annotations are more limited, they’re metadata that needs to be extracted through reflection.

A Type-Safe LLM Tool Definition Framework In Scala

Now that we know what the problems are and what tools we have available to solve these problems, we can actually build a fairly elegant solution. Let’s break it down:

Why will Idea-1 not work?

Let’s go back to what we wanted to implement:

@Tool(

name = "get_weather",

description = "Retrieves current weather for the given location."

)

def getWeather(

@Param(

description = "City and country e.g. Bogotá, Colombia",

required = true

)

location: String,

@Param(

description = "Units the temperature will be returned in.",

enum = Array("celsius", "fahrenheit"),

required = false

)

units: String = "celsius"

): String = ???

Based on what we know now, if we tried to write a function that takes function as a generic and tries to generate the schema for it:

import scala.reflect.runtime.universe._

@Tool(

name = "get_weather",

description = "Retrieves current weather for the given location."

)

def getWeather(

@Param(description = "City and country e.g. Bogotá, Colombia")

location: String,

@Param(description = "Units the temperature will be returned in.")

units: Option[String]

): String = ???

def generateSchema[T](func: T)(implicit tag: TypeTag[T]): Unit = {

val tpe = tag.tpe

println(s"Function type: $tpe")

val args = tpe.typeArgs

args.foreach(t => println(s"- $t"))

}

/*

Output:

Function type: (String, Option[String]) => String

- String

- Option[String]

- String

*/

One immediate problem you may notice here is that the parameter names are dropped. So we don’t actually have access to the name “location” or “units” which makes serialization / de-serialization here a challenge. This is mainly due to compile-time meta-programming support in Scala 2. Case classes on the other hand, preserve this information, and they’re actually sufficient to get the complete setup working. Here’s how you do it for a case class.

def extractCaseClassInfo[T: TypeTag]: Unit = {

val tpe = typeOf[T]

// Get primary constructor parameters

val constructorSymbol = tpe.decl(termNames.CONSTRUCTOR).asMethod

val constructorParams = constructorSymbol.paramLists.flatten

println(s"Case class: ${tpe.typeSymbol.name}")

println("Fields:")

constructorParams.foreach { param =>

val name = param.name.toString

val paramType = param.typeSignature

println(s" - $name:")

println(s" Type : $paramType")

}

}

extractCaseClassInfo[WeatherArgs]

/*

Case class: WeatherArgs

Fields:

- location:

Type : String

- units:

Type : Option[String]

*/

Idea-2

object TemperatureUnit extends Enumeration {

type TemperatureUnit = Value

val CELSIUS, FAHRENHEIT = Value

}

case class WeatherArgs(

@Parameter(description = "The city and state, e.g., Bangalore, IN")

location: String,

@Parameter(description = "The unit for the temperature")

unit: Option[TemperatureUnit.Value] = None

)

@Tool(name = "get_current_weather", description = "Get the current weather in a given location")

class WeatherTool extends ToolExecutor[WeatherArgs] {

def execute(args: WeatherArgs): String = {

s"The weather in ${args.location} is 72 degrees ${args.unit.getOrElse(TemperatureUnit.FAHRENHEIT)}."

}

}

Okay, this is pretty similar to the Pydantic example and also a pretty clean interface to provide to developers. Can we implement this successfully?

Defining the Abstraction

We need a few base components to get the above abstraction to work:

Annotations

Annotations in Scala will allow us to mark tools and their parameters. We can create an annotation like so:

class Tool(val name: String, val description: String) extends StaticAnnotation

class Parameter(val description: String) extends StaticAnnotation

Now, we can take our case class, annotate it and then read these descriptions during runtime via reflection like so:

def readAnnotation[T: TypeTag]: Unit = {

val tpe = typeOf[T]

// Helper to extract string literal from an annotation argument

// This will go through the `Tree` exposed by reflection, find the correct annotation

// variable via a constant `index` and return the value (or `default` if none exists).

def extractStringArg(args: List[Tree], index: Int, default: String): String =

args.lift(index).collect {

case Literal(Constant(s: String)) => s

}.getOrElse(default)

// Read @Tool annotation from class

tpe.typeSymbol.annotations

.find(_.tree.tpe =:= typeOf[Tool])

.foreach { ann =>

val args = ann.tree.children.tail

val name = extractStringArg(args, 0, "Unknown")

val desc = extractStringArg(args, 1, "No description")

println(s"Tool: name = $name, description = $desc")

}

// Read @Parameter annotations from constructor params

val constructorParams = tpe.decls

.collectFirst { case m: MethodSymbol if m.isPrimaryConstructor => m }

.map(_.paramLists.flatten)

.getOrElse(Nil)

constructorParams.foreach { param =>

param.annotations

.find(_.tree.tpe =:= typeOf[Parameter])

.foreach { ann =>

val desc = extractStringArg(ann.tree.children.tail, 0, "No description")

println(s"Parameter: ${param.name} -> $desc")

}

}

}

readAnnotation[WeatherTool]

// Tool: name = get_current_weather, description = Get the current weather in a given location

readAnnotation[WeatherArgs]

// Parameter: location -> The city and state, e.g., Bangalore, IN

// Parameter: unit -> The unit for the temperature

A ToolExecutor Base Trait

The next thing we need is a fixed format that all tool calls should follow. This is a very solved problem, we can just define an abstract class and ensure that all our tools extend this class. We can have an execute method that we require all our tools to define. This would be the function that’s called when the LLM makes the tool call and wants to execute our tool.

However, a class like this would need to grab the type information of the parameters passed to the tool via a generic. And this is information that’s deleted at runtime. So, we need to also have a TypeTag that’s implicitly loaded in our class that automatically persists this information from compile time to runtime. This is the field we’ll be performing our reflection operations on to generate the function schema during runtime. Apart from the TypeTag, we’ll also store the Class[_] object which is kind-of the Java class spec for our type T grabbed via the reflection API. This will come in handy later when we want to instantiate a class later during de-serialization.

abstract class ToolExecutor[T: TypeTag] {

def execute(args: T): String

// Capture the TypeTag for later use

private[aiutils] val typeTag: TypeTag[T] = implicitly[TypeTag[T]]

private[aiutils] lazy val argClass: Class[_] = {

val mirror = typeTag.mirror

mirror.runtimeClass(typeTag.tpe.erasure)

}

}

Generating the Function Schema

Now, we can finally put all of this together and use Scala’s reflection API to extract all this information and auto-magically generate the JSON schemas for the LLM tool calls at runtime. Let’s walk through how we can implement this functionality.

def extractProperties(tpe: Type): (Map[String, Any], List[String]) = {

// These are the two main things the LLM tool call API needs.

// Properties is a `Map` of argument -> description that contains argument description & type information

// Required is a `List` that contains all the arguments that the LLM is required to populate

val properties = mutable.Map[String, Any]()

val required = mutable.ListBuffer[String]()

// Let's start by fetching the primary constructor and grabbing the `paramList`

val constructor = tpe.decl(termNames.CONSTRUCTOR).asMethod

val params = constructor.paramLists.head

params.foreach { param =>

val paramName = param.name.toString

val paramType = param.typeSignature

// Check if it's an Option type. This is to populate the `required` list.

val (actualType, isOptional) =

if (paramType.typeConstructor =:= typeOf[Option[_]].typeConstructor)

(paramType.typeArgs.head, true)

else (paramType, false)

if (!isOptional) required += paramName

// Extract the @Parameter annotation

val description = param.annotations

.find(_.tree.tpe =:= typeOf[Parameter])

.flatMap(extractDescriptionFromAnnotation)

.getOrElse(s"Parameter $paramName")

// Generate JSON schema for this parameter. We can later augment this to handle different LLM formats easily by just modifying the `typeToJsonSchema` function.

val schema = typeToJsonSchema(actualType) + ("description" -> description)

properties(paramName) = schema

}

(properties.toMap, required.toList)

}

Handling Complex Types

One of the “pretty” things about this approach is that it’s functional in nature. Kind of. We can naturally handle nested structures with recursion.

// This is sometimes LLM specific. But we can handle that repetetive logic here by handling the boilerplate duplication at the lowest layer.

private def typeToJsonSchema(tpe: Type): Map[String, Any] = {

if (tpe =:= typeOf[String]) {

Map("type" -> "string")

} else if (tpe =:= typeOf[Int] || tpe =:= typeOf[Long]) {

Map("type" -> "integer")

} else if (tpe <:< typeOf[List[_]] || tpe <:< typeOf[Seq[_]]) {

// Go recursion!

val elementType = tpe.typeArgs.headOption.getOrElse(typeOf[String])

Map("type" -> "array", "items" -> typeToJsonSchema(elementType))

} else if (tpe.typeSymbol.isClass && tpe.typeSymbol.asClass.isCaseClass) {

// Go recursion! (2)

val (nestedProps, nestedRequired) = extractProperties(tpe)

Map("type" -> "object", "properties" -> nestedProps, "required" -> nestedRequired)

} else if (tpe.toString.endsWith(".Value")) { // Scala Enumerations

// Extract enum values through reflection. Go Claude!

val enumPath = tpe.toString.stripSuffix(".Value")

val moduleSymbol = cm.staticModule(enumPath)

val moduleMirror = cm.reflectModule(moduleSymbol)

val enumInstance = moduleMirror.instance.asInstanceOf[Enumeration]

Map("type" -> "string", "enum" -> enumInstance.values.map(_.toString).toSeq)

} else throw new Exception(s"Cannot convert type to JSON schema: $tpe")

}

This handles everything from primitive types to complex nested structures with arrays of objects—exactly what you need for real-world tools. One shitty thing about this is that the Exception for when I can’t auto-magically parse something is thrown only at runtime. Even though all the information is available at compile-time. Sad. But hey, as long as you make sure all your tool creations are unit-tested, not the biggest problem. But in Scala 3 I believe you should be able to implement all of this logic using compile time reflection.

De-Serialization for Function Execution

The final piece is executing tool calls. We need to:

- De-Serialize the JSON arguments from the LLM into the

Argsclass. - Instantiate the case class

- Call the tool’s execute method

We can implement the Registry pattern here and do something like this:

// Add a `generate` function to our `ToolSchemaGenerator`, something like:

object ToolSchemaGenerator {

def generate[T: TypeTag](executor: ToolExecutor[T]) = {

val tpe = typeOf[T]

// Extract tool annotation...

// Extract properties and required fields...

// Return a schema object

SchemaObject(

`type` = "function",

function = FunctionSchema(...)

)

}

// .. The rest of the code

}

// ---

class ToolRegistry {

private val tools = mutable.Map[String, (ToolExecutor[_], LlmTool)]()

def register[T: TypeTag](executor: ToolExecutor[T]): Unit = {

val schema = ToolSchemaGenerator.generate(executor)

tools(schema.function.name) = (executor, schema)

}

def execute(name: String, jsonArgs: String): Try[String] = {

tools.get(name) match {

case Some((executor, _)) =>

Try {

// Use Jackson to deserialize JSON to the case class

val args = mapper.readValue(jsonArgs, executor.argClass)

// Safe cast because we know the types match

executor.asInstanceOf[ToolExecutor[Any]].execute(args)

}

case None =>

Failure(new NoSuchElementException(s"Tool '$name' not found"))

}

}

}

Note that this only works because we stored the Class[_] object in the ToolExecutor, which Jackson (our JSON library) can use to deserialize the JSON into the correct type.

The Final Result

With all these pieces in place, using the framework is fairly simple (I think?):

@Tool(name = "get_current_weather", description = "Get the current weather in a given location")

class WeatherTool extends ToolExecutor[WeatherArgs] {

def execute(args: WeatherArgs): String = {

s"The weather in ${args.location} is 72 degrees ${args.unit.getOrElse(FAHRENHEIT)}."

}

}

// Register it

val registry = new ToolRegistry()

registry.register(new WeatherTool())

val schemas = registry.getToolSchemas

makeLlmCall(messages, schemas) // <- Make the LLM calls

// Execute tool calls from the LLM

val result = registry.execute("get_current_weather",

"""{"location": "Bangalore, IN", "unit": "CELSIUS"}""")

makeLlmCall(messages ++ result, schemas) // <- Or whatever ...

Overall, it’s a pretty nice framework. To the end-user, all the complexities of:

- Generating type-checked JSON schemas for their Scala functions

- Generating description information for their Scala parameters & functions for the LLM

- Deserializing the LLM tool-call responses to type-checked argument classes

- Executing these tools and sending it back to the LLM

Are more or less completely abstracted out and kept “under-the-hood.” Pretty neat.

There’s more we can do here for sure. We can probably add some type validation and tool composition logic here as well, but that’s for when I’m not as lazy :)