De-Novo Assembly & Overlap Graphs

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Preface & References

I document topics I’ve discovered and my exploration of these topics while following the course, Algorithms for DNA Sequencing, by John Hopkins University on Coursera. The course is taken by two instructors Ben Langmead and Jacob Pritt.

We will study the fundamental ideas, techniques, and data structures needed to analyze DNA sequencing data. In order to put these and related concepts into practice, we will combine what we learn with our programming expertise. Real genome sequences and real sequencing data will be used in our study. We will use Boyer-Moore to enhance naïve precise matching. We then learn indexing, preprocessing, grouping and ordering in indexing, K-mers, k-mer indices and to solve the approximate matching problem. Finally, we will discuss solving the alignment problem and explore interesting topics such as De Brujin Graphs, Eulerian walks and the Shortest common super-string problem.

Along the way, I document content I’ve read about while exploring related topics such as suffix string structures and relations to my research work on the STAR aligner.

De-Novo Assembly

Now that we’ve covered the section where we worked on the genome reconstruction problem (DNA Sequencing) assuming the existence of another genome from the same species, what do we do when there exists no such previously reconstructed genome? Such a situation can occur when we’re studying the genome of a new exotic species or simply lack access to said genome. This was the problem that the original scientists who worked on the Human Genome Project had to deal with and the problem is indeed far more computationally intensive than when we already have a snapshot to work with.

Core Ideas

To slowly build up to the solution, let us first understand the key ideas involved in the problem. We essentially have many, many short reads of DNA sequences from the main genome and need to somehow piece them back together to reconstruct the original genome. To reiterate, we are given these short reads in no particular order and have no picture of where to match these short reads inorder to reconstruct the main sequence.

To solve this problem, let us begin by working back from the final solution.

!

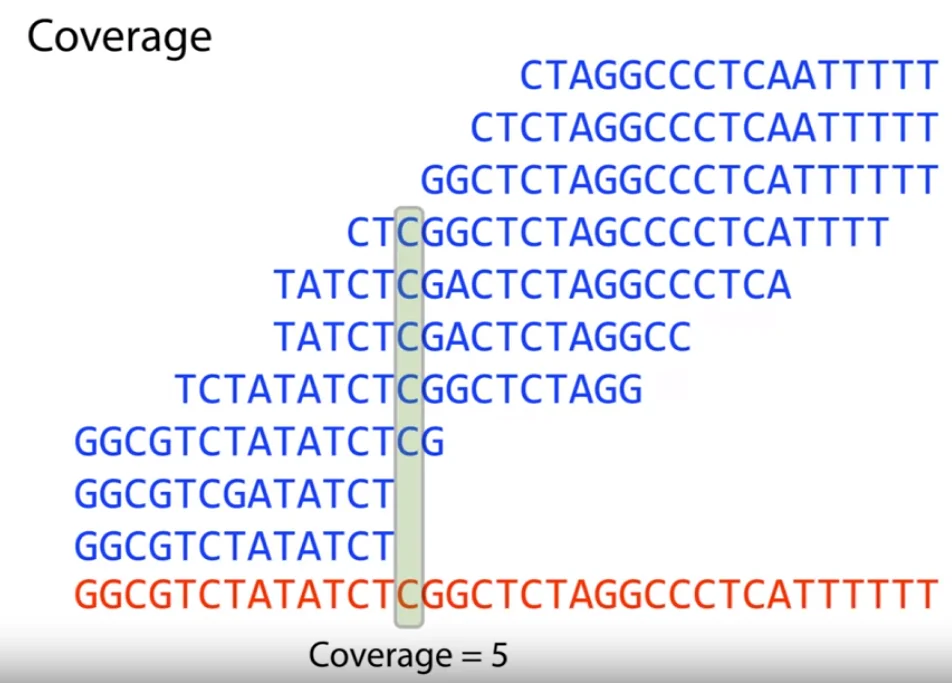

Let’s suppose we did know the positions of the short reads in the original sequence. We then define the term coverage as the number of overlapping reads for each character $c$ of the main genome. We can then simply define a term average coverage as the coverage we can expect for each character of the sequence given the length of the sequence, length of each read and the total number of short reads we have of the sequence.

$$\text{Avg. Coverage} = \frac{\text{Length of read } * \text{ Number of reads}}{\text{Length of genome}}$$For the above example, the value comes out to be around $5$ (simply round to the nearest integer). We hence call this a 5-fold coverage of the genome. Now notice that if we have two overlapping reads, the suffix of one read is very similar to the prefix of the next read. This follows from the fact that they are overlapping consequence reads. From this, we get the two laws of assembly.

If a suffix of read $A$ is similar to a prefix of read $B$, then $A$ and $B$ might overlap.

More coverage leads to more and longer overlaps.

Repeats are bad. (Will be discussed later.)

Note that in the first law we again use the term similar, because there can be errors. These mainly stem from DNA sequencing errors and from polyploidy. That is, species can have two copies of each chromosome, and these copies can differ slightly.

Overlap Graphs

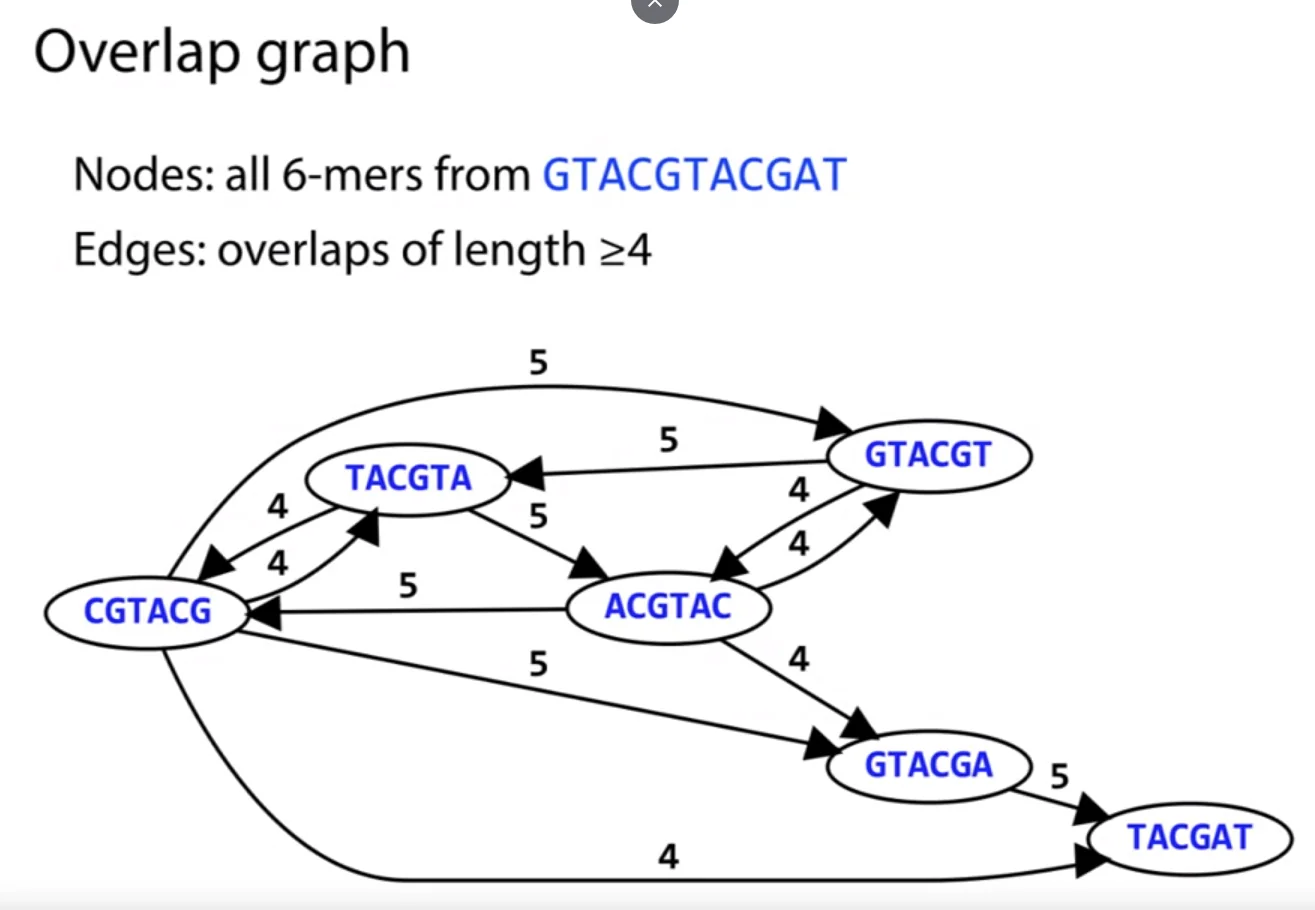

We define overlap graphs for a particular set of reads as follows.

Let the nodes of the graphs represent the reads we have obtained of the genome. Now, there exists an edge $e$, between an ordered pair of nodes $(u, v)$ when a suffix of $u$, overlaps with the prefix of $v$.

Now, not all overlaps are equally important. For example, an overlap of size $1$ can be very frequently occurring and doesn’t provide much evidence of it occurring due to it being consequent overlapping reads in the genome. Hence, we can build overlap graphs where an edge $e$ exists between an ordered pair of nodes $(u, v)$, only when the overlap between them exceeds some constant value. Consider the following overlap graph for overlaps of size $\geq 4$