DP as DAGs, Shortest Path on DAGs & LIS in O(nlogn)

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Over the past few notes, we learned about developing efficient strategies to solving computational problems by using the greedy idea (Set Cover & Approximation Algorithms, More Greedy Algorithms! Kruskal’s & Disjoint Set Union, Activity Selection & Huffman Encoding). The greedy idea focuses on choosing the most optimum solution at a local stage and reducing what’s left to a subproblem with the same structure. This is great when problems have a locally optimum solution and have optimal substructure properties. But what do we do when this is not the case? What to do when greedy does not work?

Dynamic Programming

Dynamic programming is a technique used to efficiently solve problems that check the optimal substructure criteria. If we are able to reduce the given problem to smaller subproblems with the same structure, then we can employ a technique similar to divide and conquer. The idea here is that we can model a problem as a transition of sorts from the solution to its subproblem. If this is true, then it is possible that we might have a LOT of overlapping subproblems. Notice that instead of repeatedly recomputing the solutions to these subproblems, we can store them in memory somewhere and simply look up the solution for a specific subproblem in $O(1)$ instead of recomputing it.

Visualizing DP as DAGs

A very interesting view of visualizing DP was discussed. DP is usually presented as some form of DP table, transition states, and magic for loops that compute the answer to some problem. I often find this extremely unintuitive and difficult to follow along with. DP by nature is nothing but the idea of recursively solving a problem by splitting it into smaller problems and applying memoization whenever possible to overlapping subproblems.

A very cool way to visualize this is by modeling the recursion tree for solving a problem in terms of DAGs (directed acyclic graphs).

We mentioned that DP relies on a problem having a recursive solution. That is, it must be possible to model it as a transition from the solution to its subproblems.

Note that if we attempted to visualize this recursive method of solving as a graph, with some solutions dependent on the solution of its subproblems, we can never have a cycle. The presence of a cycle would imply that a problem depends on its subproblem and the subproblem depends on its parent. Computing this would lead to an infinite cycle.

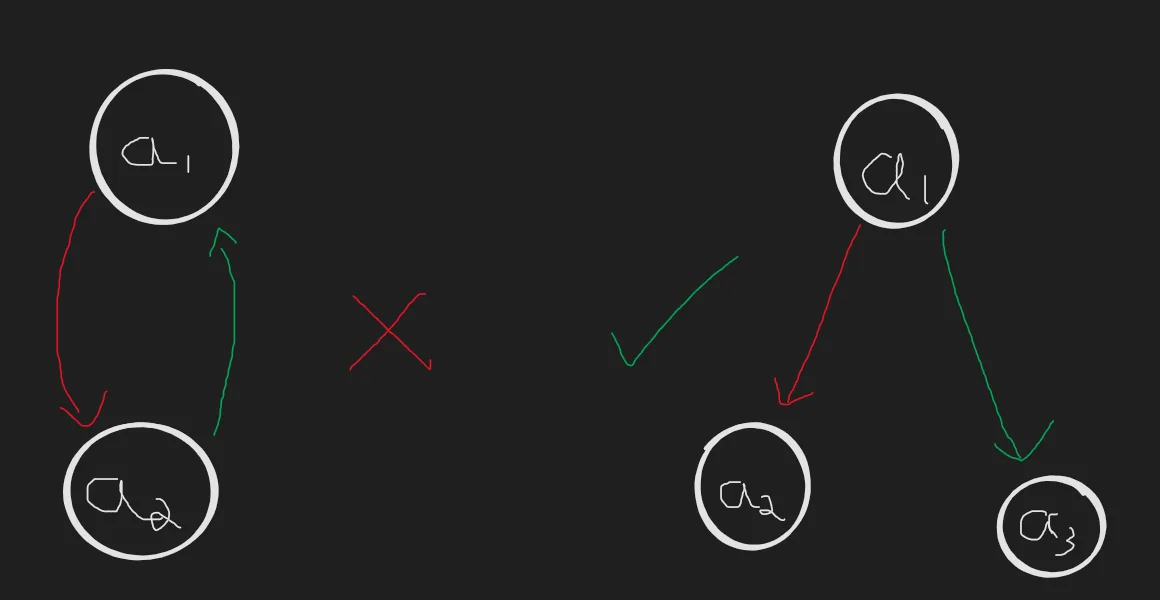

Say we wish to compute $a_1$. For the problem structure depicted on the left, it is impossible to compute it recursively as we would be in an infinite cycle. The problem on the right however can be solved by independently computing the solution for $a_2, a_3$ and then computing $a_1$.

This also means that we can think of every recursive problem in some kind of DAG-like structure.

Visualizing Fibonacci

Consider the famous Fibonacci problem. We can recursively state $F_n = F_{n-1}+F_{n-2}, \ _{n \gt1 }$

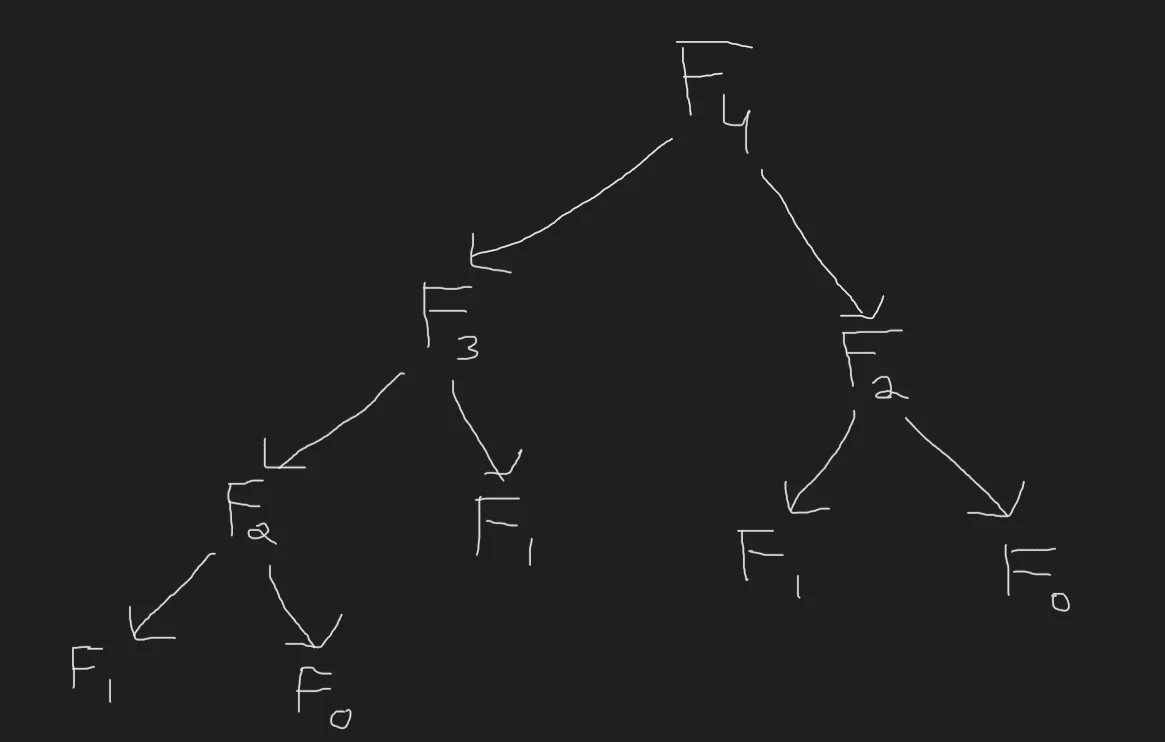

Let’s try to visualize the recursion tree for $F_4$ (which is also a DAG)

Notice that we are computing $F_2$ multiple times. (Assume $F_0$ and $F_1$ are known constants).

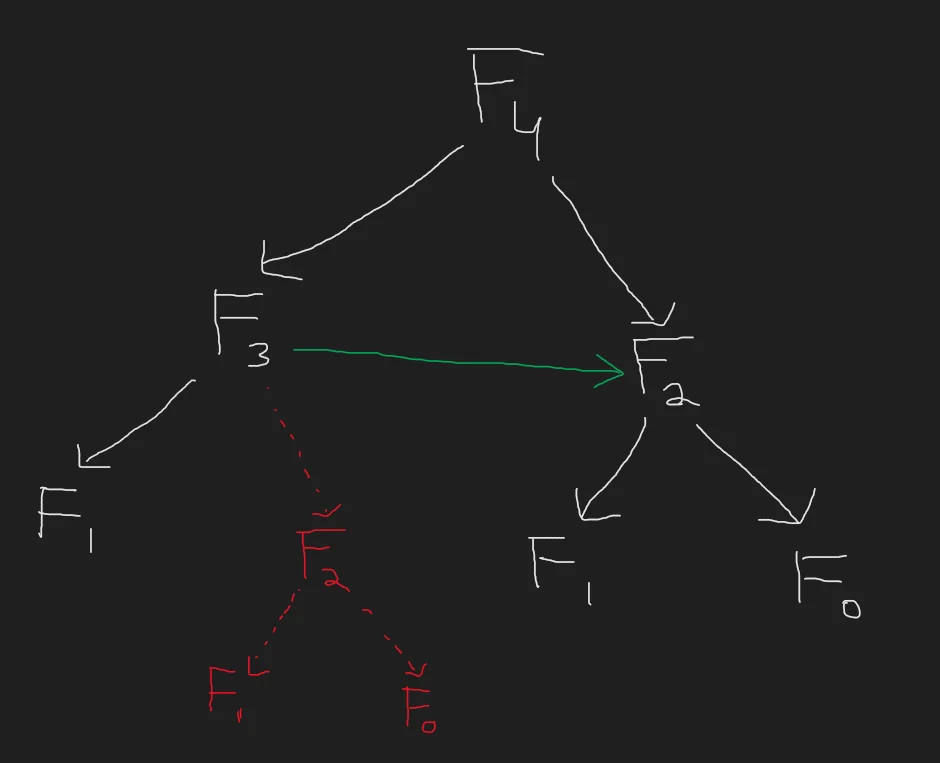

We can eliminate this overlap by computing it just once. This allows us to model the DAG as follows,

By using the once computed $F_2$ to compute $F_3$, notice that we managed to eliminate an entire subtree of recursion. This is the core idea behind DP. By saving the states of previous computations, we are effectively able to eliminate recomputation for all overlapping subproblems, thus considerably reducing the complexity of our solution.

Note that DP is essentially a brute force. It can recursively try a greedy/brute force over all possible solutions for a smaller subproblem, then use this to again use the same strategy and solve a bigger problem. DP allows us to apply brute force to the problem by reducing it into smaller subproblems which we can attempt to solve using brute force / other techniques.

The shortest path on a DAG

Consider the problem of the shortest path on a DAG. The problem simply asks, “Given a DAG with V vertices and E weighted edges, compute the shortest path from Vertex $v_i$ to every other vertex on the graph.”

On normal graphs without negative edge weights, the Dijkstra algorithm can compute the solution in $O(V+ElogV)$ time. But given that our graph is directed, and has no cycles, can we do better?

In fact, yes we can. A very simple solution exists to this problem which is capable of computing the answer in just $O(V+E)$ time.

Toposort

Notice that for every DAG, there exists at least one topological sort of its vertices which is valid. This is trivially inferred from the fact that by definition, a DAG does not contain any cycles. This implies that there must be at least one arrangement where we can list vertices in a topological ordering.

A topological ordering essentially guarantees that when we reach vertex $v_i$ in the ordering, there is no path from $v_i$ to ANY vertex $v_j$ where $j \lt i$. Further, there is no path from any vertex $v_k$ to $v_i$ where $k \gt i$.

This means that the shortest path to $v_i$ will be a result of some transition from the shortest paths to all vertices $v_j$ such that $\exists \ (v_j, v_i) \in E$. And since $j \lt i$ must be true, we can simply process the vertices in topological order.

The algorithm

$$ \text{Toposort V in O(V+E)} \\ \text{Initialize all dist[ \ ] values to } \infty \\ \text{for each } v \in V-\{s\} \text{ in topological order:} \\ dist(v) = min_{(u, v)\in E}\{dist(u)+d(u,v)\} $$Notice that the recursive step in this algorithm is that to compute $dist(v)$ we require the value of $dist(u)$. Now, $dist(u)$ can always be computed recursively, but notice that because we’re going in topological order, it MUST be true that any such $u$ where $\exists (u,v)\in E$ must have already been processed. This implies that we must have already computed the value of $dist(u)$.

So instead of recursively recomputing it, we can just store the value of $dist(u)$ and access the computed value in $O(1)$.

And that’s it. We’ve managed to use Dynamic Programming to solve our problem in $O(V+E)$.

Longest path in a DAG?

What about the problem of finding the longest path from some vertex $s$ to every other vertex on a DAG? How can we efficiently compute this? Unlike with shortest path problems, computing the longest path in a general graph is NP-Complete. That is, there exists NO polynomial-time algorithm that is capable of computing the solution.

Why? A very common way to understand the longest path problem is as follows.

The longest path between two given vertices s and t in a weighted graph G is the same thing as the shortest path in a graph −G derived from G by changing every weight to its negation. Therefore, if shortest paths can be found in −G, then longest paths can also be found in G.

That is, by simply negating the weights, the longest path problem can be reduced to the shortest path problem. So… what’s the issue? Why is one NP-Complete? Note that the Dijkstra algorithm for finding shortest paths relies on the fact that all edge weights are positive. This is to ensure that there exist no negative cycles in the graph. If a negative cycle exists, the shortest path is simply $-\infty$. By negating the weights on our graph $G$, we might end up with a negative weight cycle.

However, note that this does not affect DAGs. In DAGs, the longest path problem is the same as the shortest path problem. Just, with negative edge weights. Or another way to think of it is as the exact same recursion but instead of defining $dist(v)$ as the minimum of $dist(u) + d(u,v)$ we simply define it as the maximum of the recursion. This simple change effectively changes the algorithm to the longest path solution.

for t in toposort:

for each node from t:

dp[node] = min(dp[t] + distance(t, node), dp[node]); // max for longest path

The LIS problem

The LIS (Longest increasing subsequence) problem asks the following question, “Given an ordered list of n integers, what is the length of the longest increasing subsequence that belongs to this list?”

Let’s take an example.

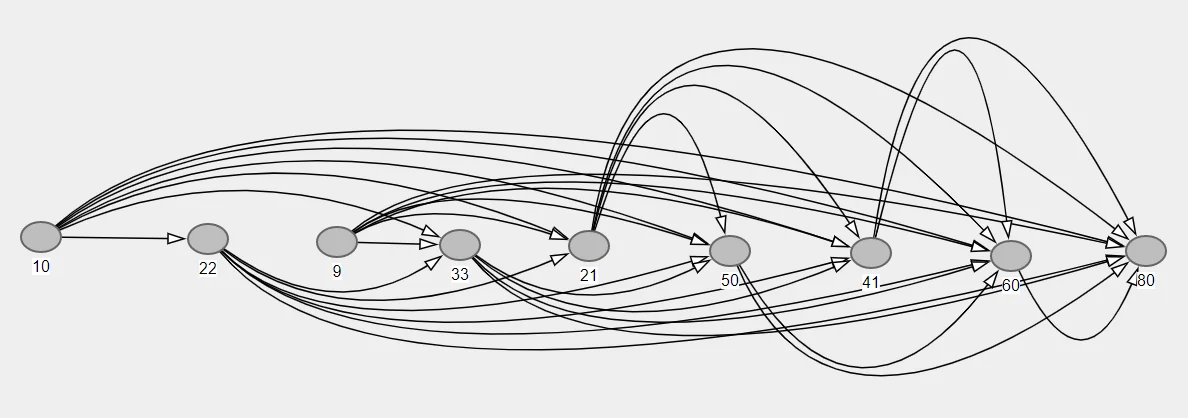

Let the list $arr$ be $[10, 22, 9, 33, 21, 50, 41, 60, 80]$. One possible solution to this list is as given below.

So how do we solve this problem?

Before we attempt to solve this problem, let us take a short detour to learn about the idea of reductions in the field of computational complexity theory. Linked here: Complexity Theory - Reductions.

Back to finding the LIS

Consider the following idea, let’s transform the given array $arr = [10, 22, 9, 33, 21, 50, 41, 60, 80]$ to a DAG by applying the following rules.

There exists a directed edge from the element at position $i$ to another element at position $j$ if and only if

- $i \lt j$, and

- $arr[i] \lt arr[j]$.

Let’s consider the implications of such a construction. What does it mean to find the LIS of some given array? Especially after this transformation.

Notice that there is no difference between the longest path on a DAG problem and finding the LIS of an array after we have performed this transformation to the array. In such a DAG, every “path” is a sequence of increasing numbers. We wish to find the longest such sequence. This, in turn, translates to simply finding the longest such path on the graph.

Our graph enumerates all such increasing subsequences. The longest path is, therefore, also the longest increasing subsequence.

We have hence, successfully found a reduction to the problem. We have shown that by applying the transformation of the array to a DAG which was constructed by following the above two rules, we have managed to reduce the problem of finding the LIS of an array to the problem of finding the longest path on a DAG.

Sadly, our reduction is not as efficient as the solution to $g$ itself. Notice that constructing the graph is of order $O(V^2)$. Let us define the construction of our graph (the reduction) as a function $R(x)$ which takes in input $x$ for problem $f$ (LIS) and converts it to input for problem $g$ (Longest path on a DAG.)

Our overall complexity will be $O(R(x)) + O(g(x))$. Since the reduction step is $O(V^2)$, our final solution will be $O(n^2)$. We may have up to $n^2$ edges.

Hence we have a solution to the LIS problem which computes the answer in $O(n^2)$.

Simply transform it to the increasing subsequence DAG and compute its longest path.

However, the natural question to ask again is, can we do better?

Computing LIS in $O(nlogn)$

The reduction to convert the LIS problem to the longest path on DAGs was great and gave us an $O(n^2)$ solution. But how can we do better? Is there any redundancy in our computation? Is there some extra information unique to this problem that we haven’t exploited yet?

Turns out, there is.

Let’s define our DP state as follows.

$\text{Let } dp[i] \text{ be the smallest element at which a subsequence of length } i \text{ terminates.}$

If we can compute $dp[i]$ for all $i$ from $1 \ to \ n$, the largest $i$ for which $dp[i]$ contains a valid value will be our answer. How do we compute this? Consider the following naïve algorithm, here $a$ is our input array and $dp$ is our dp table.

dp[0 to n] = ∞

d[0] = -INF

for i from 0 to n-1

for j from 1 to n

if (dp[j-1] < a[i] and a[i] < dp[j])

dp[j] = a[i]

Why is the above algorithm correct? Notice that the outer-loop is essentially trying to decide where to include the value $a[i]$. Further, notice that when we are iterating over $i$, the inner loop will never assign a value to any $dp[j]$ where $j \gt i+1$.

Intuitively this makes sense because at this point in time we are only considering the first $[0, i]$ segment/subarray. Such a subarray only has $i+1$ elements and can hence not be part of any $dp[j]$ where $j \gt i+1$. If we look at what the algorithm is doing, $a[i]$ can only replace $dp[0 \ to \ i+1]$. Notice that after $i+1$, $dp[j] \geq a[i]$. This means the replacement can never happen.

Notice that according to our algorithm, the condition $dp[j-1] \lt a[i] \text{ and } a[i] \lt dp[j]$ implies that the LIS of length $j-1$ must be lesser than $a[i]$ and $a[i]$ must be lesser than whatever the current computed smallest element is which terminates a LIS of length $j.$ The first part of the condition makes sure the LIS is increasing and the second part makes sure it is the smallest such element that fits the condition.

Key observation: Note that we will at most, update one value and the DP array will always be sorted.

Why? Note that $dp[i]$ is the smallest element at which an increasing subsequence of length $i$ terminates. The keyword here is smallest.

This implies that, if in the future, $dp[i]$ is replaced by some $a[j]$, then $a[j]$ is the smallest element which terminates an increasing sequence of length $i$. What is the implication of this sentence?

If $a[j]$ is the smallest element that terminates an increasing sequence of length $i$, then it can never be the smallest element in the array that terminates an increasing sequence of any length $\gt i$. The fact that it is used at position $i$ means that any such terminating value for any position $\gt i$ must be $\gt a[i]$.

If this is understood, then we have inferred that the array is both sorted and we require at most one replacement in each iteration of the outer loop. We have managed to transform the inner loops job into a simpler problem. The inner loop is actually trying to solve the following question, “Given a sorted array, what is the first number that is strictly greater than $a[i]$?”

Note that the above question can be trivially solved using binary search. This means that our inner loop can be replaced with a simple binary search to achieve $O(nlogn)$ overall time complexity.

Code

// Sample psuedo code

int lis(int arr[], int n) {

int dp[n+1] = INF;

d[0] = -INF;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int j = upper_bound(dp, dp+n+1, a[i]); // Computed in log(n) by binary search

if (dp[j-1] < a[i] && a[i] < dp[j])

dp[j] = a[i];

}

for (int i = n; i >= 0; i--)

if (dp[i] < INF) return i;

}

References

These notes are old and I did not rigorously horde references back then. If some part of this content is your’s or you know where it’s from then do reach out to me and I’ll update it.

- Professor Kannan Srinathan’s course on Algorithm Analysis & Design in IIIT-H

- Huffman Codes: An Information Theory Perspective - Reducible