"In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm (Extended Version)" - RAFT

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Abstract

These notes are taken from my reading of the original paper, In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm (Extended Version) by Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout, a video lecture by Diego on YouTube: Designing for Understandability: The Raft Consensus Algorithm and another by Core Dump: Understand RAFT without breaking your brain.

Abstract Raft is a consensus algorithm for managing a replicated log. It produces a result equivalent to (multi-)Paxos, and it is as efficient as Paxos, but its structure is different from Paxos; this makes Raft more understandable than Paxos and also provides a better foundation for building practical systems. In order to enhance understandability, Raft separates the key elements of consensus, such as leader election, log replication, and safety, and it enforces a stronger degree of coherency to reduce the number of states that must be considered. Results from a user study demonstrate that Raft is easier for students to learn than Paxos. Raft also includes a new mechanism for changing the cluster membership, which uses overlapping majorities to guarantee safety.

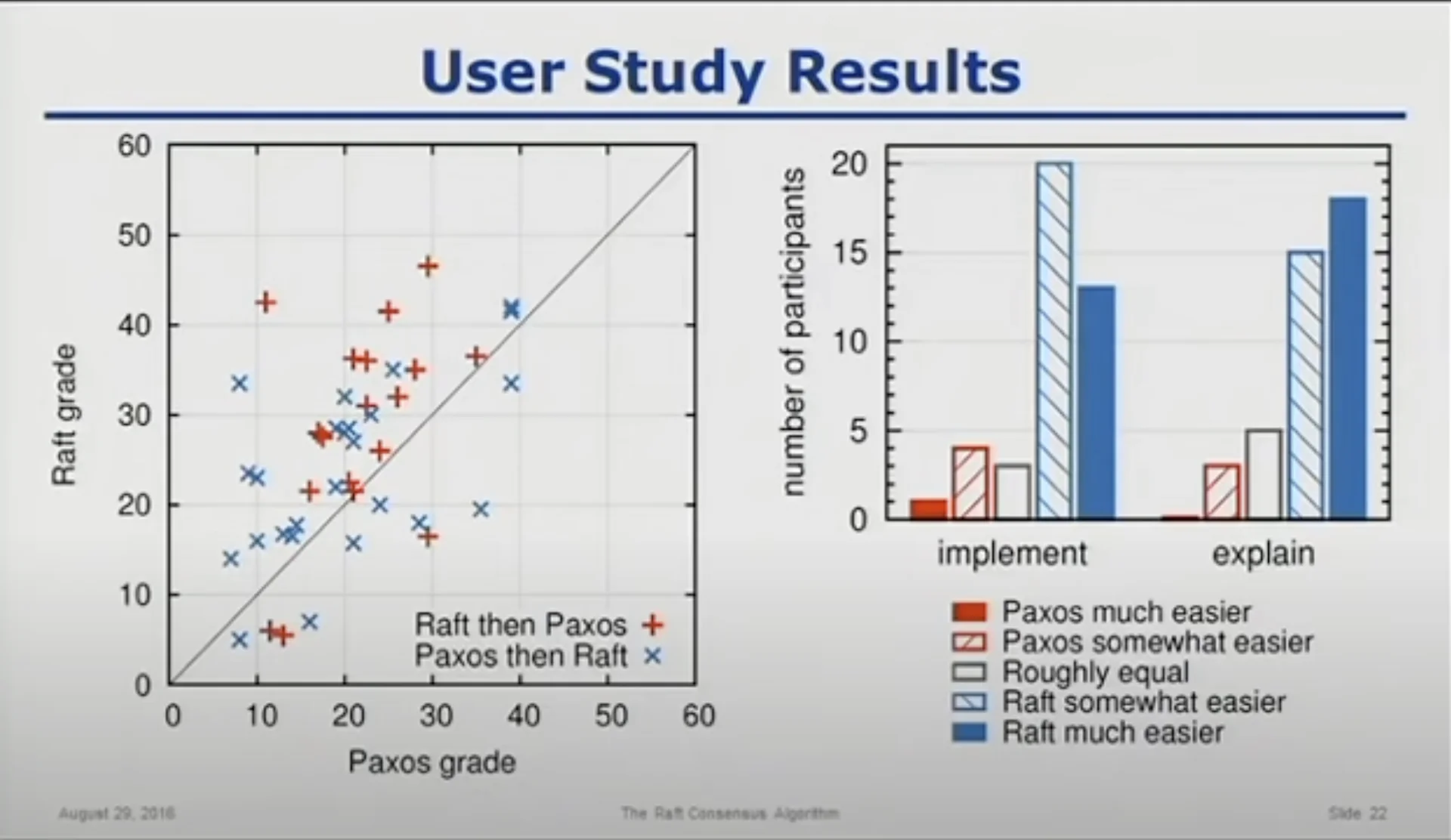

So if you’ve read that, you’ll realize that Raft was preceded by Paxos, the first popular consensus algorithm. A natural question to ask is why I’m reading / covering RAFT before Paxos. I’m doing this primarily trusting this tiny “study” conducted by Diego and John. People were roughly taught Paxos & Raft in differing orders and then made to take a “comparably equal” in difficulty quiz. You’ll notice that Raft is comparably easier (according to the participants) to implement / explain & the test results do seem to show higher “understanding” of RAFT. Regardless, you’ll also notice that people who were taught Paxos, and then Raft, did statistically significantly worse in both tests :) I personally am inclined to believe this could be because of an artifact / bias in the testing process but it is interesting. Anyways, on to Raft.

Designing Algorithms for Understandability

In the field of algorithms research, the two primary most common and important criteria used for evaluation are correctness and efficiency. In fact, that’s more or less what I wrote about a year back in How to Analyze Algorithms? Proving a Lower Bound for Comparison Based Sorting as well. However, Diego claims that a crucial yet frequently overlooked aspect of evaluation is the algorithm’s understandability. Most people interested in / researching algorithms (including me) often tend to chalk up how “intelligent” or “great” an algorithm is based on how difficult & complex it is. Complex algorithms are harder to understand, and we attribute more ‘respect’ to them, but an algorithm that is a lot more ‘understandable’ is often considered “inferior.”

But the true ‘value’ or impact of an algorithm is often in its clarity and ease of understanding. When we want to actually move from theory to practice, the ability to implement and adapt an algorithm is crucial. Especially in the field of distributed systems, reasoning about correctness of algorithms is very difficult. Adding complexity here spawns various branches and adapted versions of the same algorithm & makes it difficult to implement, greatly impacting the ability of academia to come to an agreement on the ‘best’ version and also on how much impact the algorithm can have in the real world.

Raft was a great example of the above. The paper was rejected 3 times at major conferences before it was finally published in USENIX ATC 2014.

- “Understandability” was hard to evaluate

- Reviewers at conferences were uncomfortable with understandability as a metric

- Complexity impressed reviewers However, on the adoption side:

- 25 implementations were already in the wild before the paper was even published

- It was taught in MIT, Stanford, Harvard, etc. in graduate level OSN classes before the paper was published. Kind of ironic that the same people thought teaching it to students was a great idea but didn’t think it was “good enough” to be accepted in conferences.

- Today, RAFT is the goto algorithm of sorts for most distributed consensus problems, forming the base for sharded and replicated database systems like TiDB - A Raft-based HTAP Database.

Consensus Algorithms: An Overview

Consensus algorithms are fundamental in distributed systems as they enable a collection of machines to operate cohesively despite individual failures. They ensure that a group of unreliable machines can function as a single reliable entity. The Paxos algorithm, developed by Leslie Lamport in the late 1980s, has long been the gold standard for consensus algorithms.

Paxos works by agreeing on a single value through a two-phase process involving proposers and acceptors. It is proven to be theoretically robust, but the proof is extremely difficult to understand. This also means it is very difficult to implement in practical scenarios. The complexity increases when you extend Paxos to manage replicated logs, which is essential for ensuring that all machines maintain a consistent view of the system’s state.

The Challenges with Paxos

We hypothesize that Paxos’ opaqueness derives from its choice of the single-decree subset as its foundation. Single-decree Paxos is dense and subtle: it is divided into two stages that do not have simple intuitive explanations and cannot be understood independently. Because of this, it is difficult to develop intuitions about why the singledecree protocol works. The composition rules for multiPaxos add significant additional complexity and subtlety. We believe that the overall problem of reaching consensus on multiple decisions (i.e., a log instead of a single entry) can be decomposed in other ways that are more direct and obvious.

- Complexity in Understanding: Paxos, while theoretically sound, is challenging to grasp due to its intricate processes and numerous edge cases. The basic algorithm involves selecting a proposal number, handling responses from acceptors, and ensuring consistency across distributed nodes. This complexity often leaves practitioners struggling to understand why and how Paxos works, which hampers its practical application.

- Scalability and Practicality: Paxos’s basic form addresses only a single value agreement and does not inherently cover the full range of issues needed for building a replicated log. Extending Paxos to handle multiple values, log replication, and system failures introduces additional complexity and can lead to inefficiencies and inconsistencies.

- Lack of Agreement on Solutions: Various enhancements and adaptations of Paxos have been proposed (e.g., Paxos Made Simple, Paxos Made Practical), but there is no consensus on the best approach. This fragmented understanding contributes to the difficulty in implementing Paxos effectively.

Properties of Consensus Algorithms

- Safety: They guarantee safety under non-Byzantine conditions (e.g., network delays, packet loss).

- Availability: They remain functional as long as a majority of servers are operational. For example, in a five-server cluster, any two can fail. Servers fail by stopping but can recover and rejoin from stable storage.

- Timing issues (faulty clocks, delays) may affect availability, but not consistency.

- Generally, a command completes when a majority respond to one round of calls, so a minority of slow servers don’t impact the performance of the entire cluster.

The RAFT Algorithm

Designing For Understandability

RAFT was built from the ground up keeping understandability as their north star. “Understandability” is obviously a subjective term and one that is difficult to quantify and analyze. However, the author’s attempted this challenge by using two techniques that are “generally” acceptable.

- Problem Decomposition - Wherever possible, divide the problems into separate subproblems that can be solved independently. As a competitive programmer, I can definitely agree that this is a popular implicit technique most competitive programmers use for problem solving. Take a problem, break it into individual components that you can solve independently, and link the output of one sub-problem to the input of another. Instead of solving a single complex problem, we can now easily reason the solution(s) of the smaller & simpler components and then understand how they link to one another to understand the complete solution.

- Reduction of State Space - Again, one of the things a problem solver tries to do is always reduce the number of cases to consider. When constructing a solution for a problem, you always want to try to apply operations to the problem which tries to combine multiple output scenarios into a single scenario that you can handle separately. In short, if the state space is large, you will end up with too many individual components to solve & link back together, making the solution extremely difficult to understand. On the other hand, if you can merge multiple scenarios into one, the number of components to solve & link reduces, making the solution much easier to understand.

The authors use these two techniques extensively whenever faced with design decisions for their algorithm, and that is how they came up with the final RAFT algorithm.

Novel Features

RAFT is similar to many existing consensus algorithms, but it also has several novel features.

- Strong leader: Raft uses a stronger form of leadership than other consensus algorithms. For example, log entries only flow from the leader to other servers. This simplifies the management of the replicated log and makes Raft easier to understand. This is similar to how The Google File System handles write operations.

- Leader election: Raft uses randomized timers to elect leaders. This adds only a small amount of mechanism to the heartbeats already required for any consensus algorithm, while resolving conflicts simply and rapidly. This is one of the situations in the paper where the idea of “Reduction of State Space” makes them choose an unconventional idea as the main tie-breaking mechanism for their election. This might be non-deterministic, but it is incredibly useful to reduce the state space & simplify the solution.

- Membership changes: Raft’s mechanism for changing the set of servers in the cluster uses a new joint consensus approach where the majorities of two different configurations overlap during transitions. This allows the cluster to continue operating normally during configuration changes.

The Algorithm

As mentioned previously, RAFT works by decomposing the log consensus algorithm into smaller components that are solved independently and then linked together. RAFT works by first electing a distinguished leader who is responsible for managing the replicated log. All writes go to the leader, who writes to log and then replicates the same on all other servers. When the leader fails (or is disconnected from other servers), a new leader is elected. RAFT can be divided into the following phases:

- Leader election: a new leader must be chosen when an existing leader fails

- Log replication: the leader must accept log entries from clients and replicate them across the cluster, forcing the other logs to agree with its own

- Safety: the key safety property for Raft is the State Machine Safety Property. if any server has applied a particular log entry to its state machine, then no other server may apply a different command for the same log index. The solution involves an additional restriction on the election mechanism.

Basics

Server States

Servers in Raft operate in one of three states:

- Leader: The active server managing log entries and communication with followers.

- Follower: Passive servers that wait for instructions from the leader. If a client contacts a follower, the follower redirects it to the leader.

- Candidate: A server that becomes active when it times out and tries to become a leader.

Terms

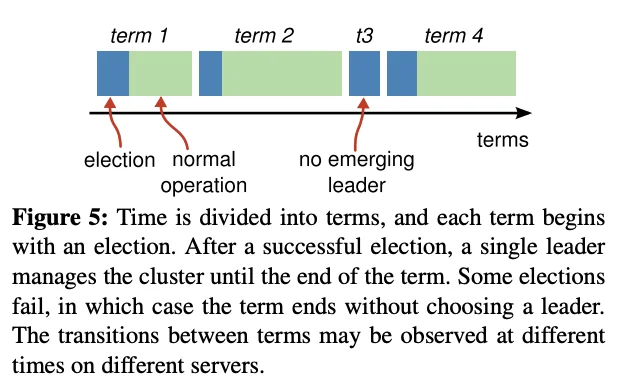

Terms are time intervals of arbitrary length. A term begins with an election. Elections occur until a candidate is chosen as leader. There is at most one leader for a given term.

Different servers may observe the transitions between terms at different times, and in some situations a server may not observe an election or even entire terms. Terms act as a logical clock in Raft, and they allow servers to detect obsolete information such as stale leaders. Each server stores a current term number, which increases monotonically over time. Current terms are exchanged whenever servers communicate; if one server’s current term is smaller than the other’s, then it updates its current term to the larger value. If a candidate or leader discovers that its term is out of date, it immediately reverts to follower state. If a server receives a request with a stale term number, it rejects the request.

RPCs

RAFT assumes that the servers communicate with one another through a procedure similar to RPCs. RAFT only requires servers to support two unique RPCs to work. This is another example of how “simple” RAFT is.

- RequestVote RPCs -> These are initiated by candidates during elections to request for votes

- AppendEntries RPCs -> These are sent from the leader to the follower servers to replicate log-entries. It also has an additional role of serving as a heartbeat message to the follower servers. (An AppendEntries RPC with an empty entry is considered a heartbeat message) Finally, if we want to also allow for transferring snapshots between servers we need a third RPC. Servers will retry RPCs if they do not receive a response in a timely manner, and they issue RPCs in parallel for best performance.

Leader Election

RAFT relies on a heartbeat mechanism to trigger leader elections. The key idea here is using randomization to introduce non-determinism into the election procedure. This technique allows RAFT to drastically reduce the size of the resultant state space, greatly simplifying the solution and making it easier to understand intuitively. On startup, all servers start out as followers. Followers will continuously listen for the AppendEntries RPC from the leader in a timely manner. What do I mean by timely manner?

Let’s say we have servers $s_1, s_2, \cdots, s_n$. Each server is assigned a randomly picked timeout value $t_1, t_2, \cdots, t_n$. This value $t_i$ is called the server $i$’s election timeout. If a follower $i$ receives no communication from the leader for an entire time period of $t_i$, it assumes that there is no viable leader and begins a new election. So in short, each server has a ticking timer that starts from $t_i$ and ticks to 0. Let’s workout the possible states.

State Space:

Success: Server $s_i$ receives communication from leader within the time period $t_i$, i.e., before its ticking timer hits 0. $s_i$ immediately resets it’s timer back to $t_i$ and restarts the countdown. If the communication from the leader contained an action, it will respond accordingly. (Actions are described below under “Log Replication.”)

Probable Failure: Server $s_i$ does not receive any communication from the leader before its timer hits 0. This could’ve occurred due to several possibilities:

- The leader crashed -> No communication was sent to $s_i$. We need to start an election to get a new leader.

- There was a network partition -> If there is a network partition separating the leader from its followers, this is as good as not having a leader (leader crash). Server $s_i$ may be a part of the minority or majority of the network partition. In either case, it needs to start an election. If it’s in the minority, a leader will never be chosen. If it’s in the majority, a leader is chosen and majority in the network partition continues to work as normal.

- There was severe message delivery latency between leader & follower -> This is likely a sign of an unhealthy leader or unhealthy network layer. If the leader’s outgoing message latencies are high, the leader is in an unhealthy state and should be replaced, i.e., we need to start an election. On the other hand, if the network layer for messages delivered between all servers has degraded, we would either need to fix the network layer or increase the lower bound on the randomized timeout periods assigned to the servers.

As we can see, in all possible root-cause states, the follower timing out before a heartbeat was received implies that we must start a new election to vote for a new leader and solve the problem. Network layer degrading is not very common and signifies bigger problems for the entire deployment as a whole. But we can easily modify the algorithm to just increase the lower bound on the randomly assigned $t_i$ for each server if a spike is observed in the number of elections conducted to solve this issue.

Alright, so from the initial state, one of the servers must timeout before all the others (due to randomized $t_i$ values, the chance of two independent servers picking the same $t_i$ is relatively low). This server will immediately start an election by incrementing its term and sending the Request Vote RPC in parallel to all the other servers. A candidate continues in this state until one of three things happens:

- It wins the election

- Another server wins the election and establishes itself as leader

- A period of time goes by with no winner.

Before we discuss these three outcome states, let us discuss how servers vote for other servers. Each server will vote for at most one candidate in a given term, on a first-come-first-served basis. That is, the server which time out first will vote for themselves and send Request Vote RPCs to all the other servers. If a server receives a Request Vote RPC before timing out, they will immediately vote for the first server in a given term that they receive a Request Vote RPC from. Let’s analyze the state space of an individual server and see how it handles the three possible situations.

State Space:

- One Candidate Wins: This is the positive path. With high probability, one of the servers that time out the earliest will send RequestVote RPCs first to the majority of the other servers and collect votes from all of them. If a candidate receives majority of the votes, it promotes itself to leader and begins issuing heart beat Append Entries RPCs to the rest of the servers to establish itself as leader and prevent further elections.

- Another Candidate Wins: This server timed out, became a candidate & sent out Request Vote RPCs. However, another server also timed out in a close interval and due to variance in message communication latency, was able to receive more votes from the remaining servers. In this case, the server that won the election will promote itself to leader and send out heartbeat RPCs to this candidate server. To verify if it was beaten in the election, it only has to check if the heartbeat message received was from a server with a term greater-than or equal to its own. If it is, then the leader is legitimate and the candidate immediately transitions into a follower state. If the term is lesser, the RPC is rejected. (Likely it is from a server that is far behind sync due to performance issues or crash-recovery).

- Split-Vote: It is possible that multiple followers became candidates at roughly the same time, and were able to all win a significant portion of the votes due to message latency. In this case, no candidate server would’ve received sufficient votes to become a leader & thus all the candidate servers would be waiting in limbo indefinitely. To solve this issue, each candidate again has a randomized timeout (can be the same $t_i$) that is used to timeout and start a new election. When this happens, the server increments its term again. This is crucial.

It is important to understand that in the split-vote case, the solution reduces back to the original problem of missing a leader and requiring a new election only because of the term increment step. If this is not done, it is possible for the server to vote for multiple candidates in the same term & also doesn’t solve the no-majority issue. But incrementing the term allows the problem to be reduced back to the original no-leader case. If the split-vote case happened frequently, we would be stuck in an indefinite loop of starting elections and voting for leaders and not have any compute available to process action requests. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the split-vote case happens rarely.

Raft uses randomized election timeouts to ensure that split votes are rare and that they are resolved quickly. To prevent split votes in the first place, election timeouts are chosen randomly from a fixed interval (e.g., 150–300ms). This spreads out the servers so that in most cases only a single server will time out; it wins the election and sends heartbeats before any other servers time out.

Note: This is a slightly simpler version of the actual leader election implemented / described by the RAFT algorithm. In practice, this solution works for electing a leader correctly. However, when we try to use RAFT to maintain a consistent log across multiple servers we will need to add another condition to make it work. Again, sticking true to the original idea of solving subproblems independently, the above algorithm is a complete solution for the leader election problem. We will address the problem of maintaining a consistent log under the following section on “Log Replication” as a minor-tweak to leader election.

Visual Demo

The visualization tool on the Raft Website does an incredible job at explaining the algorithm visually. Here are a few pictures demonstrating it at work, although I highly recommend you to actually try playing around with it to get a better intuition for the state space & its transitions.

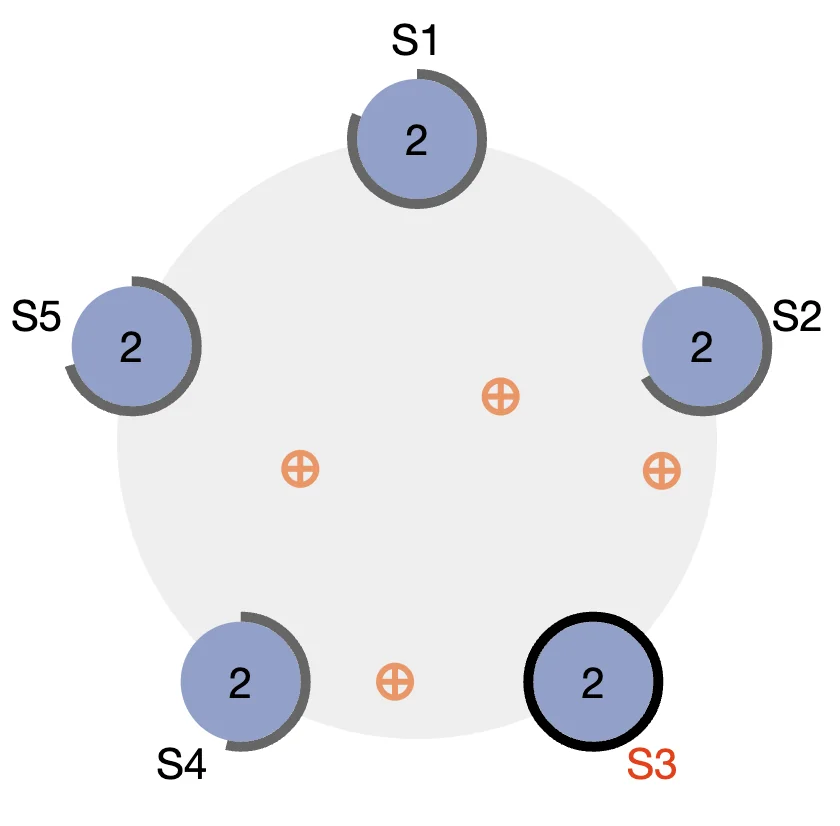

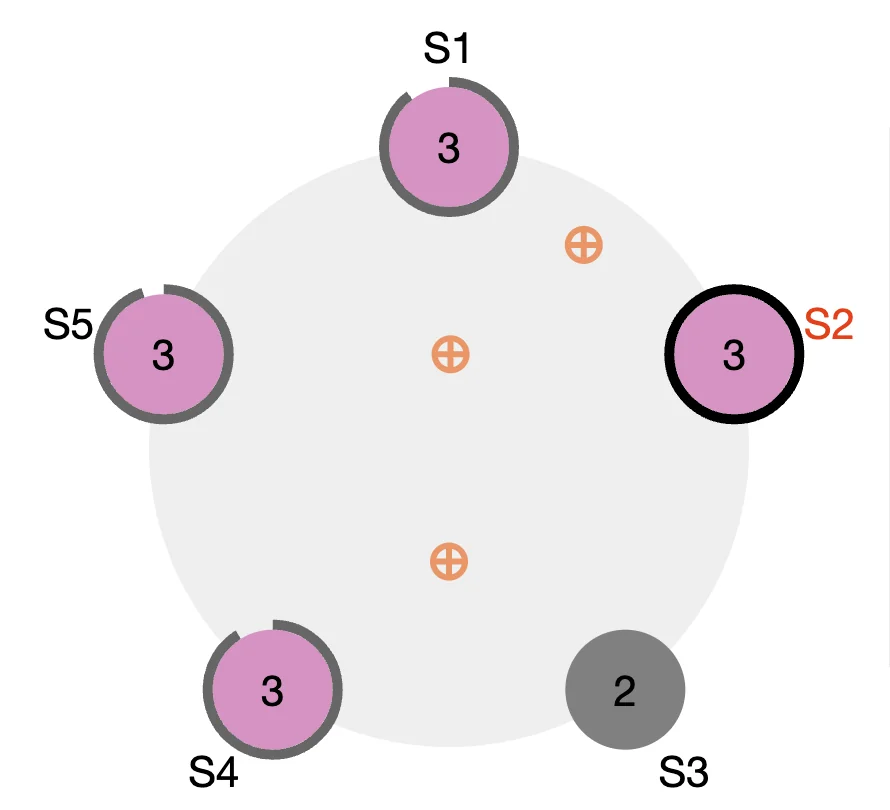

Let’s assume all the servers are on second term and S3 is the leader. Normal operation would look like this:

The circles around each server show what stage of the timeout they are at. The orange circles represent the parallel heartbeat RPC communication between leader S3 and the rest of the servers. Now let’s say we crash S3.

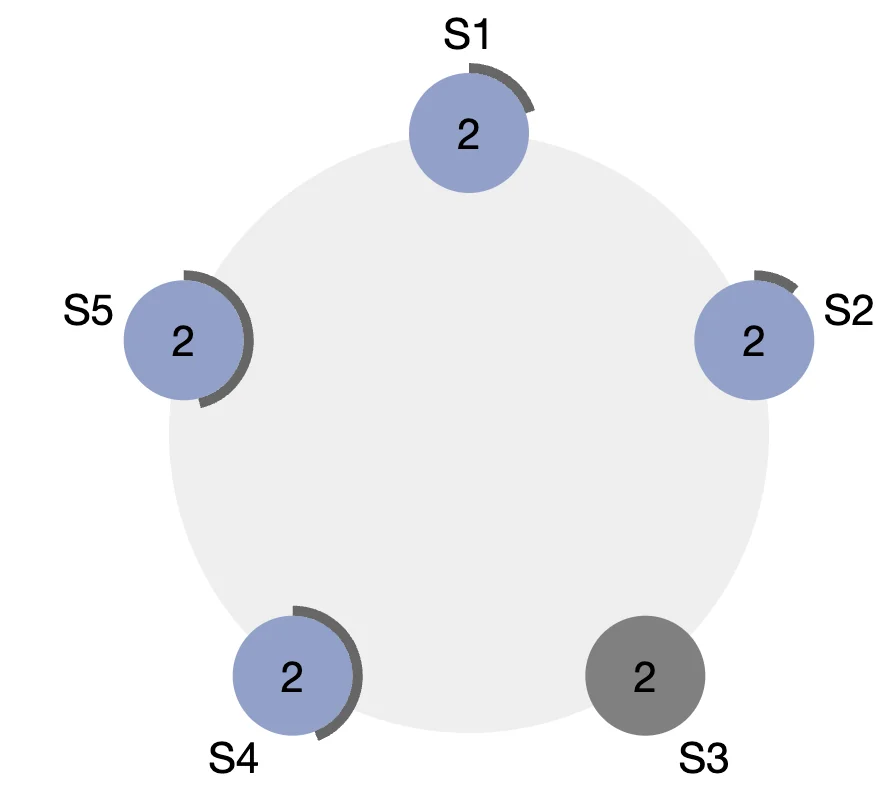

Without the heartbeat. The other servers eventually timeout.

We can clearly see that S2 is the closest to timing out here. Therefore, with high probability, S2 times out first and manages to increase its term and send the Request Vote RPC first to the majority of the other servers. These servers then see that S2 has a higher term and since it is the first Request Vote RPC they have received for this term, vote for S2. S2 receives the majority of the votes and becomes a leader. It then starts issuing heartbeats to the other servers and acts like a normal leader.

Log Replication

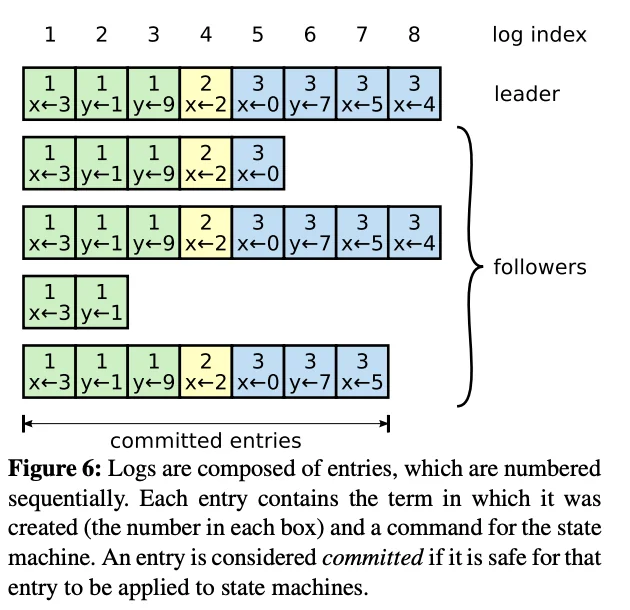

In short, the leader receives client commands, appends them to its log, and replicates them to follower logs. Once a command is safely replicated, it is executed by all servers. The RAFT log can be used to simulate a consistent state across any set of finite state machines. You can think of each entry $e_{t_i}$ in the log as an input which triggers a transaction from the server state $s_i$ to some state $s_j$ based on the log entry at time $t_i$. Inductively, as long as the servers all started with the same initial state and as long as all the log entries before time $t_i$ match between all the servers, all the servers at time $t_i$ would be on the exact same FSM state.

Logs are organized as shown below:

Short Description of Log Replication

Note that log entries have two values associated with them, an index and a term. These two metadata integers are sufficient for RAFT to replicate logs correctly. As mentioned previously, all client interactions are modeled as “append write transition entry” to the master node. When the leader node gets a new log entry from a client, it performs something similar to a 2-phase commit. Upon receiving the entry, it immediately broadcasts a Append Entry RPC to all the other nodes in the cluster. These nodes respond back to the leader once they have appended their logs. Once the leader observes that a majority of the nodes in the cluster have appended the log, it applies the log entry operation to its own FSM and issues a commit to all the other followers. On receiving a commit, the follower nodes also apply the log entry operation to their own FSM.

However, due to leader failures, randomization in elections and variance in message communication latency, it is possible that different nodes can have differing logs. It is the leader’s responsibility to ensure that all its followers eventually reach a log state that is consistent with it’s own log. To achieve this, when a leader sends a log entry to a follower, it also sends with it the index and term of the previous entry in its log. If the follower’s previous log entry does not match the one described by the leader, then the follower deletes the last entry in its log and the RPC is rejected. Then the leader retries appending its previous entry to the follower until an RPC succeeds. After this, the leader can simply append the rest of the entries one by one as they are guaranteed to match. And obviously,

If desired, the protocol can be optimized to reduce the number of rejected AppendEntries RPCs. For example, when rejecting an AppendEntries request, the follower 7 can include the term of the conflicting entry and the first index it stores for that term. With this information, the leader can decrement nextIndex to bypass all of the conflicting entries in that term; one AppendEntries RPC will be required for each term with conflicting entries, rather than one RPC per entry. In practice, we doubt this optimization is necessary, since failures happen infrequently and it is unlikely that there will be many inconsistent entries.

Now, we also introduce the one modification we said we would place on leader election previously. A follower node votes for a candidate only if:

- The candidate node’s last log entry has a higher term than the last log of the follower node

- OR the candidate node’s last log entry is on the same term as the last log of the follower node and the candidate node’s log is at least as long as that of the follower Note, we are talking about the log here. Including committed and non-committed entries.

Now as an exercise, I would recommend trying to prove that this construction ensures safety & availability requirements we mentioned earlier.

Intuitively Attempting to Prove the Construction Works

Let’s try to intuitively prove that the above construction works. Let’s note a couple of useful features of RAFT.

A term and leader are basically equivalent -> This directly follows from the leader election construction. Only one node can have the majority in an election & therefore if it wins, that term is associated with the winner node and only that node. In case of split-vote, a new election is held. Note that each election has its own term.

If two log entries have the same term number & index, they must be equivalent -> Also directly follows from the above claim. Note that in any given term, there is exactly one leader who could have issued Append Entry RPC calls. And for a given leader, it cannot issue Append Entry for the same entry multiple times with distinct indices. Therefore any two log entries with the same term number were emitted by the same leader, and therefore, if they have the same index, the contents must also be the same.

If two log entries have the same term number & index, then the prefixes of both the logs until that entry are equivalent -> This can be proven by a recursive argument. We are given two logs $L_1$ and $L_2$. Let’s say the entry at index $i$ for both $L_1$ and $L_2$ has term $t_i$. From the previous statement these entries are equivalent. Let us suppose that the leader for the term $t_i$ was $S$. Note that entry $i$ would’ve only been appended by $S$ to some log $L$ if the $(i-1)^{th}$ entry of $L$ was equivalent to the $(i-1)^{th}$ entry of $S$. Therefore, if the $i^{th}$ entry of $L_1$ and $L_2$ match, we know that their $(i-1)^{th}$ entries must also be equivalent. This follows inductively until the base state where the previous state was an empty state.

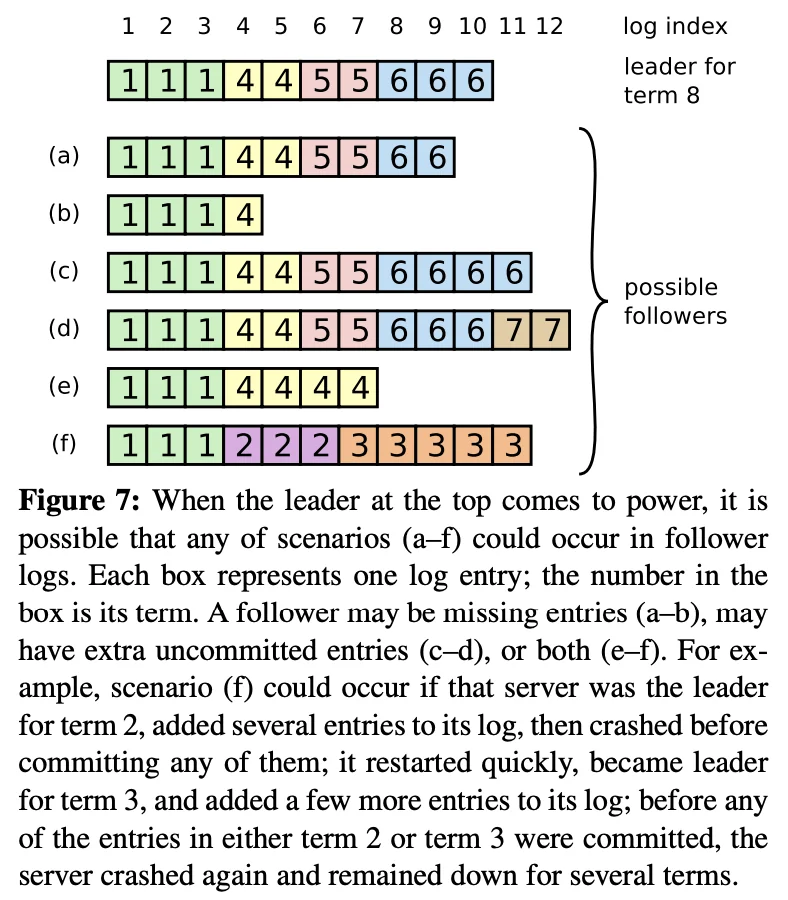

The leader will never have a log that does not match the logs committed by the majority: This is slightly harder to see. But if this is not true, the servers can all end up with matching logs but mismatched FSM state. What do I mean by this? Consider this example from the paper:

Let’s suppose the leader crashes and $(f)$ becomes the leader again. Only this time, it is able to send messages to the rest of the servers. Also let us assume that the leaders for terms 4, 5 & 6 were able to commit their entries since they had majority entry append success. In this scenario, the leader, $(a), (c) \ \& \ (d)$ have committed the entries in terms 4, 5 & 6. Therefore, they have also applied these operations to their FSM state. Now, if $(f)$ becomes the leader, it will begin to force the follower nodes to copy its own log. This means the leader, $(a), (c) \ \& \ (d)$ will pop off committed logs and apply logs from terms 2 & 3 on top of the operations from 4, 5 & 6 thus causing the servers to have inconsistent state with each other.

Note that this error occurs only because the leader that was elected did not have a log that matched the state committed by the majority of the servers in the cluster. We claim that such a situation can never happen. The proof / intuition for this comes from the special modification we made to the leader election algorithm. Let’s suppose a log $L$ was committed in the majority of the servers in the pool, but node $S$ never received it. Now, node $S$ was voted the leader for a term, i.e., node $S$ acquired a majority of votes from the pool of servers. We can apply the pigeonhole principle here to prove that if both of these statements are true, then there must exist a server in the set of servers who voted for $S$ which also has the log $L$ that was committed in the majority of the servers in the pool. Furthermore, we choose $S$ such that it is the first leader (smallest term $T$) that satisfies this property.

Now, this server $F$ would’ve only voted for $S$ if:

- (a) The last log entry in both $S$ and $F$ share the same term, and the length of $S$’s log is greater than or equal to the log of $F$. -> In this scenario, the last logs both $S$ and $F$ have been receiving logs are from the same leader. Consider the first log they received on this term. This must have matched since it’s from the same leader and the log will append only if the previous log is correct. This also means they had the same length at this point. Using the same argument(s), if $S$ has a longer length log, it must include every entry in $F$. Hence $S$ would contain $L$.

- (b) $S$’s last log entry has a higher term than the last log entry of $F$ -> Let’s call the last log of $S$, $L_T$. Now, let’s suppose that the missing committed log $L$ was issued by some leader in term $U$. We know that $U \lt T$ since $F$ contains the log but $F$’s last log has a term lesser than $T$ (Remember that the terms in the log are always monotonically increasing). Now, the node that was the leader for term $T$ contained $L$, since we assumed that node $S$ is the first leader without this committed log. Now, in the leader for term $T$’s log, $L$ would appear before $L_T$, since it contained $L$ before it received $L_T$ $(U \lt T)$ and it cannot append $L_T$ to any other node’s log without the other node’s log matching it’s log till $L_T$. Therefore, since $S$ contains $L_T$, it must also contain $L$.

In both cases, we arrive at a contradiction. Therefore, the result of this tweak is that, if a log has been committed by a leader in a previous term, it must be present in the log of every future leader. This allows RAFT to ensure that the leader will never have to delete any entry from it’s log. This means there is a strict one-way flow of logs from leaders to followers only. This is one of the key features that makes RAFT much easier to understand than other consensus algorithms where the write-flow occurs in both ways based on far more conditions that make the state space much more complex and difficult to reason about.

The FSM’s are consistent: This follows from the above where we reasoned why it is OK for the leader of any term to not have to delete any entry from it’s log. This means that “writes” flow in only one direction, from leader to follower. Remember that an entry is safe to apply to a node’s state machine only when it is committed. Commits also only flow from leader to follower. Since the leader never removed entries from it’s log & since it always contains all the logs committed by the majority in previous terms, it will never issue a log to a follower which causes a follower to have to “remove” a committed log. Therefore, for each node in the RAFT system, commits are append only and never have to be rolled back. This means that if an entry was committed by a node at any position (term, index) in it’s log, then every other server will also consequently commit the same operation at that position in the log. The FSM will be consistent.

This last property is why consensus algorithms are so powerful in distributed systems. It allows a set of machines to act as a single unit (resiliency).

When you walk through all of these scenarios, it really highlights how the specific design choices – the strong leader, the term logic, and especially the voting restriction based on log completeness – combine to make the safety properties feel intuitive rather than magically asserted. While not a formal proof, building this kind of step-by-step intuition first makes approaching the formal guarantees (like Leader Completeness and State Machine Safety) much less daunting. It’s a direct payoff of their ‘design for understandability’ goal.

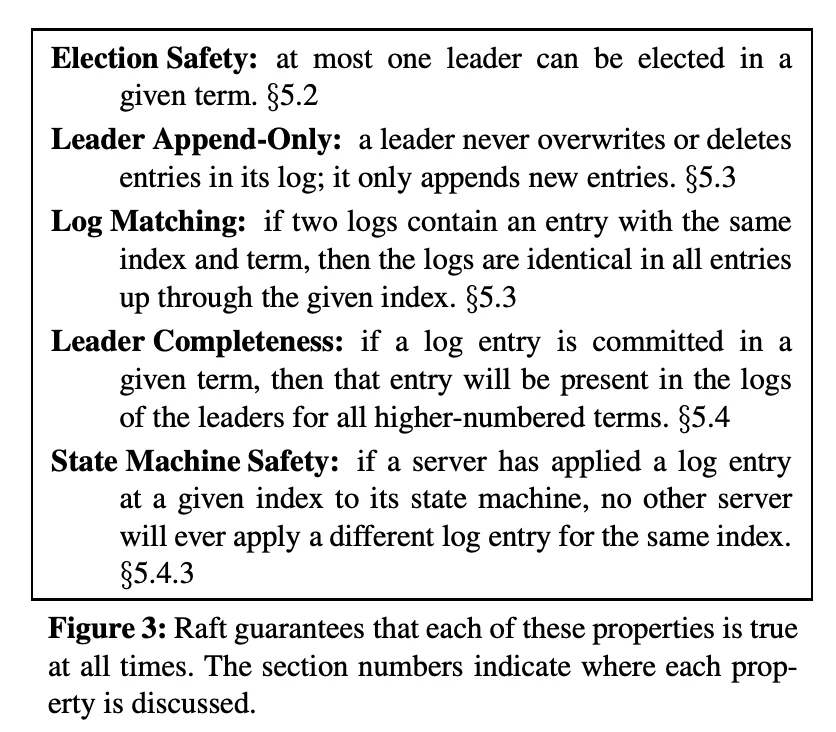

Formal Properties

Let’s formally state the properties we proved above into terms used by the paper.

- A term and leader are basically equivalent -> Election Safety

- The leader will never have a log that does not match the logs committed by the majority -> Leader Append-Only

- If two log entries have the same term number & index, they must be equivalent -> Log Matching

- The leader will never have a log that does not match the logs committed by the majority -> Leader Completeness

- The FSM’s are consistent -> State Machine Safety

Follower & Candidate Crashes

Until this point we have focused on leader failures. Follower and candidate crashes are much simpler to handle than leader crashes, and they are both handled in the same way. If a follower or candidate crashes, then future RequestVote and AppendEntries RPCs sent to it will fail. Raft handles these failures by retrying indefinitely; if the crashed server restarts, then the RPC will complete successfully. If a server crashes after completing an RPC but before responding, then it will receive the same RPC again after it restarts. Raft RPCs are idempotent, so this causes no harm. For example, if a follower receives an AppendEntries request that includes log entries already present in its log, it ignores those entries in the new request.

Cluster Membership Changes

TBD

Conclusion (Personal Thoughts)

RAFT is a great “academic” face of how simplicity is often the most powerful solution. In general, I empirically notice that the more complex, convoluted and difficult to understand something is in academia, the more ‘respect’ it’s given. In software engineering, the opposite is usually true. The biggest impact you can have as a SWE is often via the simplest solutions. This is also why there’s a lot of disdain between the two roles, but RAFT is a great example of proving that sometimes (especially in complex fields like distributed systems), making an algorithm understandable is just as crucial as making it correct and efficient. Researchers can reason about it’s behavior more easily and build even more research on top of this easier. You’re enabling future researchers to build even higher. One great example of this is TiDB - Architecture being built using RAFT for consistency.