Introduction to Complexity Theory

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Introduction to Complexity Theory

In most algorithms courses, students are taught a plethora of algorithms that are capable of solving many interesting problems. It often tends to internally suggest to the student that most problems have solutions. Solutions that are feasible to compute on their machines should they need to. On the contrary, most problems are unsolvable and even fewer are computable in any feasible amount of time.

Computation complexity theory is a field of study where we attempt to classify “computational” problems according to their resource usage and relate these classes to one another. We begin by defining a few to classify algorithms based on running time.

- $P$

- $EXP$

- $NP$

- $R$

P or PTIME

This is a fundamental complexity class in the field of complexity theory. We define $P$ as the set of all decision problems that can be solved by a deterministic Turing machine in polynomial time.

A more formal definition is given below: A language $L$ is said to be in $P$ $\iff$there exists a deterministic Turing machine $M$ such that:

- $M$ runs for polynomial time on all inputs

- $\forall l \in L$, $M$ outputs 1

- $\forall l \in L$, $M$ outputs 0

When we talk about computational problems, we like problems in $P$. These problems are feasible for computers to compute in a reasonable amount of time.

EXP or EXPTIME

This is the class of all decision problems that can be solved by a deterministic Turing machine in exponential time. Similar to how we gave a formal definition for $P$, it is easy to see that we can modify the same formal definition to fit $EXP$ as well.

R or RTIME

The $R$ here stands for “recursive.” Back when complexity theory was being developed, there was a different idea of what the word ‘recursive’ meant. But in essence, $R$ is simply the set of all decision problems that can be solved by a deterministic Turing machine in some finite amount of time.

It might seem as though all problems are solvable by a Turing machine in some finite time and hence unnecessary to have a class dedicated to it. But this is not true.

Undecidable problems

An undecidable problem is a decision problem for which it has been proven that it is impossible to develop an algorithm that always leads to a valid yes-or-no answer. To prove that there exist undecidable problems, it suffices to provide even just one example of an undecidable problem.

The Halting Problem

One of the most famous examples of undecidable problems is the halting problem, put forth by Alan Turing himself. Using this, Turing proved that there do indeed exist undecidable problems. But this isn’t just the only reason why the halting problem is “special.”

The halting problem poses the following question: “Given the description of an arbitrary program and a finite input, decide whether the program finishes running or will run forever.”

In fact, if the halting problem were decidable, we would be able to know a LOT more than what we do today. Proving conjectures would be a LOT easier and we might have made a lot of progress in many fields.

Solve Goldbach’s conjecture?

Consider Goldbach’s conjecture. It states that every even whole number greater than 2 is the sum of two prime numbers.

Using computers, we have tested the conjecture for a large range of numbers. This conjecture is “probably” true, but till today, we have no proof for this statement. Simply checking for large ranges is simply not enough. Finding even just one counter-example, even if this counterexample is 10s of digits long is enough to prove the conjecture false.

Let’s say we constructed a Turing machine $M$ that executes the below algorithm (given in pseudocode).

iterate from i : 0 -> \\infty:

iterate from j : 0 -> i:

if j is prime and (i-j) is prime:

move to next even i

if none of its summation were both prime:

output i

halt # We have disproved Goldbach's conjecture!

This definition of our Turing machine is capable of disproving Goldbach’s conjecture. But the question is, how long do we let it run for? If the number is not small, it might take years to find this number. Maybe millions of years. We do not know. And even worse, if the conjecture is indeed true, then this machine will never halt. It will keep running forever.

However, what if the halting problem was decidable?

What if, we could construct another such Turing machine $M_1$ this time which solves the halting problem? We can feed it $M$ as input, and let $M_1$ solve the halting problem.

If $M_1$ outputs “halt” then there must be some input for which Goldbach’s conjecture fails. We have disproved it.

If $M_1$ outputs “run forever” then Goldbach’s conjecture must be true. It is no longer a conjecture, we have managed to prove it!

Being able to solve the halting problem would help us solve so many such conjectures. Take the twin primes conjecture, for example, we would be able to solve it. We would be so much more powerful and armed in terms of the knowledge available to us. However, sadly, Alan Turing proved that the halting problem is undecidable. And the proof is quite fascinating to describe

The proof

We will prove that the halting problem is undecidable using contradiction. Therefore, we begin by assuming that there exists some Turing machine $M$ that is capable of solving the Halting problem.

More formally, there exists some deterministic Turing machine $M$which accepts some other Turing machine $A$ and $A$’s input $X$ as input and outputs 1 or “Halt” if $A$ will half on that input and 0 or “Run forever” if $A$ will not halt on that input.

Now, let’s construct another Turing machine “Vader” which does something quite interesting. Given some Turing machine $A$ and its input $X$, Vader first runs $M$on the input. If $M$ returns “halt”, Vader will run forever. And if $M$ returns “run forever”, Vader will halt.

This is still fine, but the masterstroke that Turing came up with was to give Vader, itself as input!

In the above explanation, we make $A = Vader$ and $X = Vader$. For Vader to work, it will first run $M$on this input. For simplicity, we will call the input program Vader as iVader. There can only be two possible outputs,

$M$ returns “Halt”

This means that $M$ thinks that iVader will halt when run on itself. However, when $M$ returns “halt”, Vader will run forever. Remember that Vader is given itself as input. The input iVader and the program Vader are identical. $M$ predicts that iVader will halt but we know that Vader will run forever. We have a contradiction.

$M$ returns “Run forever”

Again, we have ourselves a contradiction. Just like before, $M$ thinks that iVader will run forever, but we know that Vader will halt. The emphasis here is that iVader and Vader here are the same Turing machines that run on the same input.

Therefore, neither of the cases can be true. The fact that we have a contradiction here arises from the fact that our assumption is wrong. There can exist no such Turing machine $M$ which can solve the Halting problem.

NP or NP-TIME

There are a couple of different definitions used to define the class $NP$.

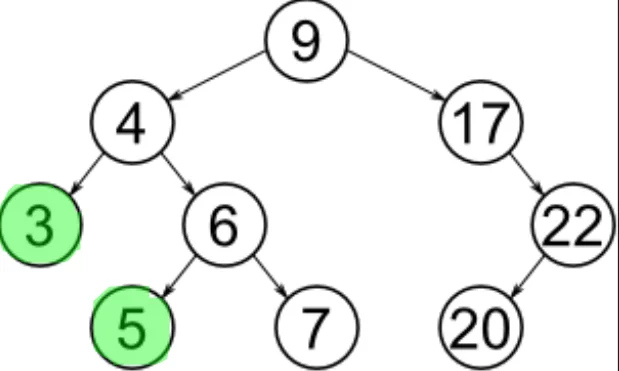

One of these definitions says, NP is the set of problems that can be solved in polynomial time by a nondeterministic Turing machine. Notice that the keyword here is nondeterministic. What this essentially means that at every “step” in the computation, the machine always picks the right path. Let’s say a Turing machine had states similar to the below picture. A non-deterministic machine would accept any input string that has at least one accepting run in its model. It is “lucky” in the sense that it is always capable of picking the right choice and moving to the right state which guarantees ending at a YES result as long as such a run exists in its model.

The second definition for $NP$ calls it the set of decision problems for which the problem instances, where the answer is “yes”, have proofs verifiable in polynomial time by a deterministic Turing machine. To understand this, we must understand verification vs decision.

Verification vs Decision

We covered what it means to solve what a decision problem is, (Defining Computational Problems, Church-Turing Hypothesis) verification is on the other hand is something you can send along with a solution. In most intuitive terms, let’s say someone claims that they are very good at the game of Tetris and can win the game for some specified input. Here we consider a modified version of Tetris where all the next pieces are known in advance. How does this person prove to you that they can indeed win the game? By playing it out of course! It might be very difficult to figure out the strategy to win, but given the proof (the sequence of moves), implementing the rules of Tetris and playing it out to check if the person is correct can be done easily.

Essentially, to be in $NP$, our machine can take an arbitrary amount of time to come up with proof for its solution for all possible inputs, but this proof must be verifiable in polynomial time.

We’ll attempt to explain further via means of an example. Consider the clique problem.

$$ \text{CLIQUE} = \{\langle G, k\rangle : G \text{ is an undirected graph with a k-clique} \} $$How would a verifier verify this answer? Let’s say the input to the verifier is given in the form $\langle \langle G, k\rangle, c\rangle$ where $c$ is the answer to our problem defined by $G$ and $k$.

- First, check if the answer $c$ contains exactly $k$ unique nodes $\in G$ or not. If no, the answer can be trivially rejected. This can be done in $O(V)$ time.

- Next, check if there exists an edge between every pair of nodes in $c$. This is done in $O(V+E)$ time. If no, reject the answer.

- If both the above checks passed, accept the answer!

Hence we can say that the clique problem is in $NP$ because we’ve demonstrated that it is indeed possible to write a verifier that can check the “correctness” of an answer. In the field of complexity theory, we call such ‘solution paths’ or ‘proofs’ or ‘witnesses’ a certificate of computation.

NP-Complete

For a problem $p$ to be $\in NP-Complete$ it must fit 2 criteria.

- $p$ must be $\in NP$

- Every problem $\in NP$ must be reducible to $p$

We cover reductions in depth later, but essentially, if we can come up with a polynomial-time algorithm(s) to ‘reduce’ the inputs and outputs $\langle I, O\rangle$ given to some machine $s$ to new inputs/outputs $\langle I', O' \rangle$ such that when applied to another machine $t$, $O' = O$. If this can be done, we say that we have reduced the problem solved by $s$ to $t$.

Now, onto P vs NP

References

These notes are old and I did not rigorously horde references back then. If some part of this content is your’s or you know where it’s from then do reach out to me and I’ll update it.

- Professor Kannan Srinathan’s course on Algorithm Analysis & Design in IIIT-H

- P vs. NP - The Biggest Unsolved Problem in Computer Science - Up And Atom (Great Channel, recommend checking out)