Multi-Agent Systems: Harnessing Collective Intelligence - A Survey

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

In my previous post (Reasoning, Acting, and Learning ; A Survey of Single-Agent LLM Patterns), I explored strategies to improve the performance of a single agent, using structures like Tree-of-Thoughts to explore complex solution spaces. However, most of these patterns are already internally implemented by frontier labs and there is not as significant a gain to expect from implementing extra compute intensive patterns on top manually.

This brings us to Multi-Agent Systems (MAS). Instead of a single monolithic agent, we can employ multiple specialized agents collaborating or debating or orchestrating to improve accuracy. Gemini tends to be good at certain tasks, Anthropic in others, etc. We can effectively utilize these ideas in practice using multi-agent architectures. Karpathy’s LLM Council is a great example! For more long horizon orchestration, there are two popular architectures which are proposed today, both by Anthropic & OpenAI.

Architectures (Manager vs. Network)

Multi-agent Systems - LangChain | A practical guide to building agents - OpenA | Building Effective Agents - Anthropic

Building Multi-Agent Systems

“Regardless of the orchestration pattern, the same principles apply: keep components flexible, composable, and driven by clear, well-structured prompts.”

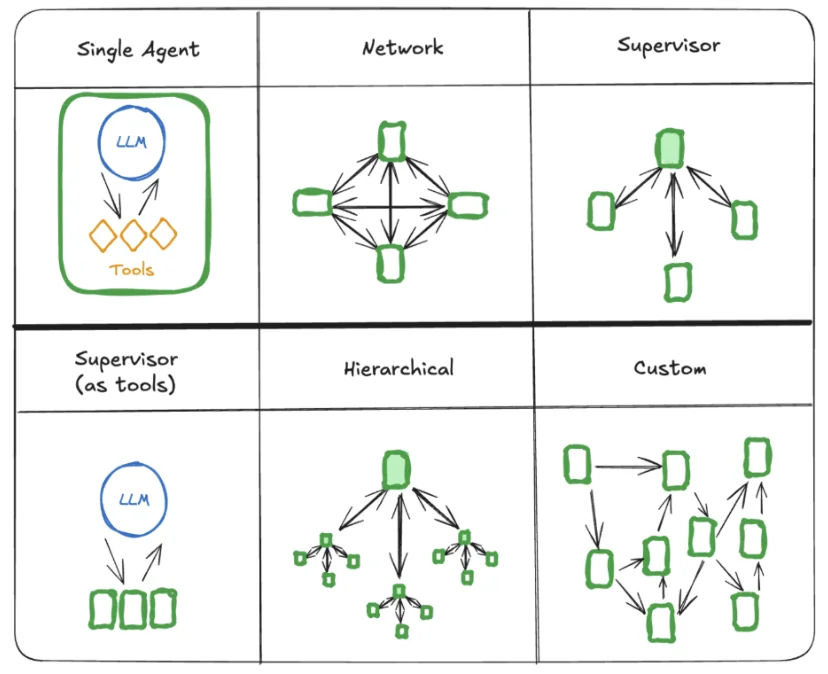

We primarily care about two architectures here. The “Manager / Supervisor” model and the “Network” model. Hierarchical / Custom come under them for the most part.

Manager

The supervisor architecture employs a central agent, to manage and direct the workflow of other specialized agents. For example, the supervisor agent receives the initial incident report and then delegates specific diagnostic tasks, such as log analysis, metric monitoring, and configuration checking, to the appropriate specialized agents. You can also involve hierarchy here which organizes agents into a tree-like structure, with supervisor agents at different levels of the hierarchy overseeing groups of subordinate agents.

Example: A Head Doctor agent gets an alert and asks the Metric Agent for CPU data and the Log Agent for errors; they report back only to the Head Doctor.

Network

In a network architecture, multiple agents interact with each other as peers who, within the system, can communicate directly with every other agent. This many-to-many communication pattern is well-suited for problems where a clear hierarchy of agents or a specific sequence of agent calls is not predefined.

Example: The Database Metric Agent detects high disk latency and directly notifies/triggers the Cloud Metric Agent to check underlying disk health.

Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) Strategies

Apart from the above defined ‘workflow’ patterns, there has also been a significant amount of exploratory research in structured interactions between different agents (as equals, as debaters in front of a ‘judge’, etc.) for improving reasoning.

MAD (Persona / Tit-for-Tat) & Degeneration-of-Thought

One new concept this paper introduces is that of Degeneration-of-Thought (DoT). It’s the idea that self-reflection mechanisms in LLMs often fail because once an LLM-based agent has established confidence in its answers, it is unable to generate novel thoughts later through self-reflection even if the initial stance is correct. To address this problem, they propose a Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) framework specifically designed to encourage divergent thinking, contradiction and debate. The core workflow is as follows:

Debate Setup

The proposed environment has two debaters, one playing the affirmative role (a ‘devil’ proposing an initial, likely intuitive but flawed solution) and the other plays the negative role (an ‘angel’ who disagrees and corrects the initial solution). These agents are prompted using a tit-for-tat meta prompt like so:

You are a debater. Hello and welcome to the debate competition. It’s not necessary to fully agree with each other’s perspectives, as our objective is to find the correct answer. The debate topic is stated as follows: .

Note that this is a key ‘hyperparameter’ for this persona-based MAD framework. The more the prompt encourages contradiction, the more it influences outcomes. For example, in benchmarks meant to challenge counter-intuitive thinking, this technique works better. But in other ‘simpler’ benchmarks, this technique actually hurts performance.

Judge

A third agent acts as a judge or moderator. It monitors the debate and has two modes:

- Discriminative*:* Decides if a satisfactory solution has been reached after a round, allowing for an early break to end the debate early.

- Extractive: If the debate reaches a limit without a clear resolution, the judge extracts the final answer based on the history.

Here’s an example of a judge prompt:

You are a moderator. There will be two debaters involved in a debate competition. They will present their answers and discuss their perspectives on them. At the end of each round, you will evaluate both sides’ answers and decide which one is correct.

MAD (Society of Minds)

Improving Factuality and Reasoning in Language Models through Multiagent Debate

This paper introduces another MAD strategy, inspired by the book Society of Mind, by Marvin Minsky (Turing Awardee, Co-founder MIT AI Lab). In this framework, they set up multiple instances of the same (or different) LLMs to act as agents engaging in a collaborative debate to refine the answer to a proposed problem over multiple rounds of debate. The process is as follows:

Debate

- Each debater agent composes an initial response to the proposed question.

- The agents are then shown the responses of the other agents and prompted with something like:

“These are the solutions to the problem from other agents: [other answers] Using the opinion of other agents as additional advice, can you give an updated response . . .”

Or

" These are the solutions to the problem from other agents: [other answers] Based off the opinion of other agents, can you give an updated response . . ."

Note that in the first one, the LLM knows its own response and hence is more likely to be stubborn about its own response. In experiments, they found the first version led to longer debates and better answers.

3. The agents converge on a single, agreed-upon answer or they hit a limit on the number of iterations and we pick the majority consensus answer.

The idea of ‘debates’ between individual agents is orthogonal to other work on improving individual agent performance. So we can still use ideas like few-shot learning, CoT / ToT / GoT, Medprompt, Reflexion, etc. to improve single-agent performance and stack this society-of-minds model on top to improve performance. They also showed that the debate doesn’t just amplify an initially correct answer present among the agents. The paper shows cases where all agents initially provide incorrect answers but arrive at the correct solution through the process of mutual critique and refinement during the debate.

However, as we’ll see in the paper comparing MAD strategies, medprompt actually beats Society-of-minds more often than not. However, I believe this similar framework can boost information sharing between individual expert agents in a framework where individual expert agents are trying to correlate information across domains and diagnose incidents.

MAD Is Not Always Better: Medprompt

While MAD has shown promising results, it’s not always better and performance can vary significantly depending on ‘hyperparameter’ (prompt) tuning and choice of dataset.

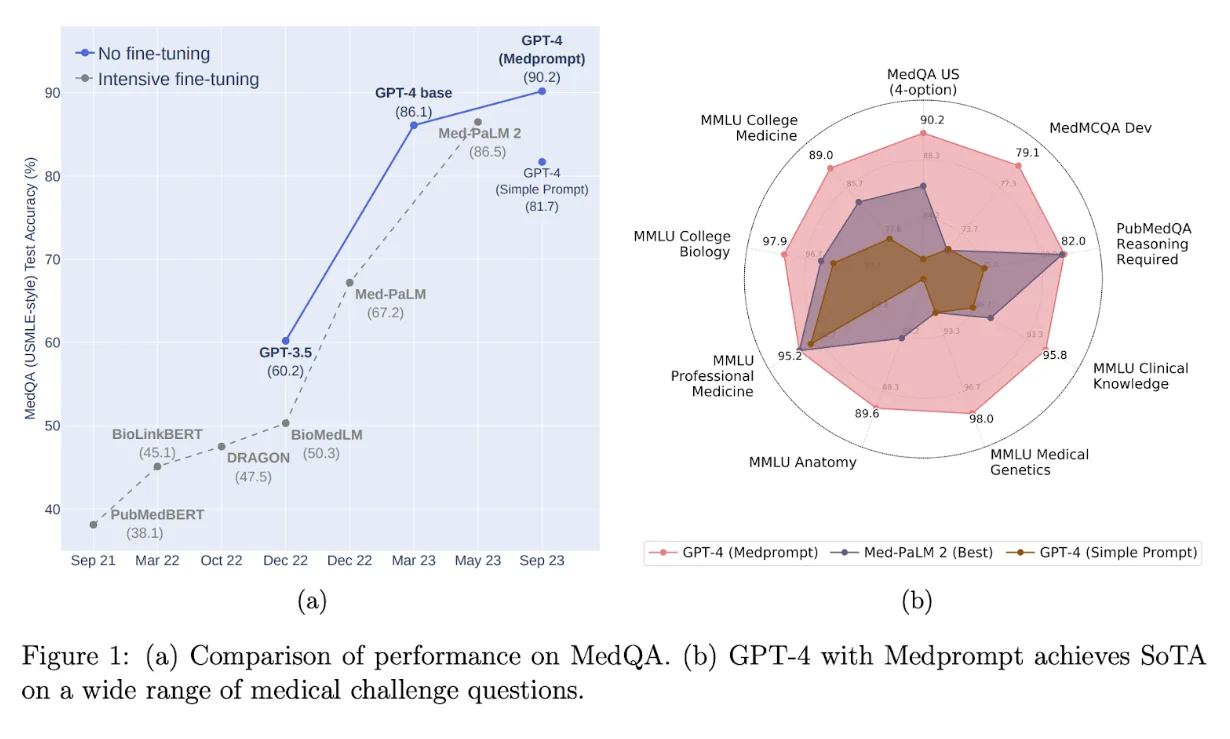

MEDPROMPT: Generalist Foundational Models Outperforming Special-Purpose Tuning via Prompt Engineering

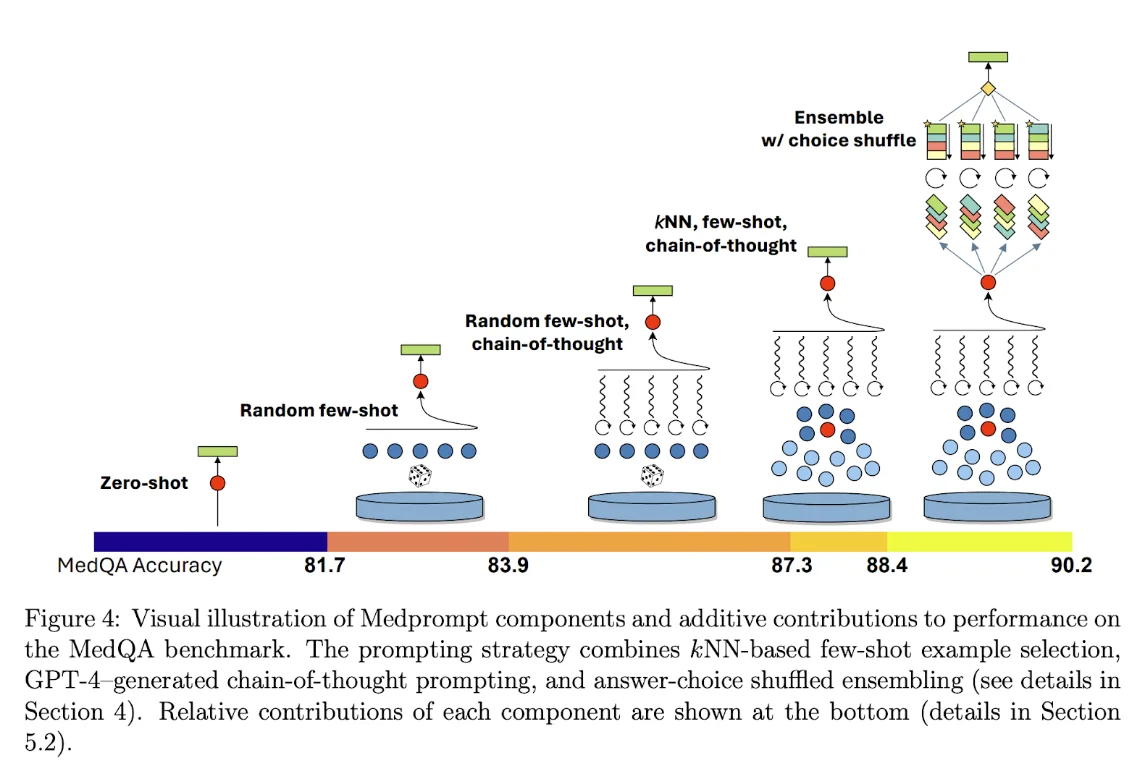

This paper attempts to prove that the ‘old’ notion of requiring domain-specific fine-tuning to achieve SOTA benchmarks is no longer necessary, and that newer models (like the then SOTA GPT-4) can match or surpass SOTA benchmark performance purely through sophisticated prompt engineering and in-context learning (ICL) techniques. They then designed a prompt-engineered setup on top of GPT-4, which achieved SOTA results on several medical benchmarks, Medprompt. There’s three core components to it:

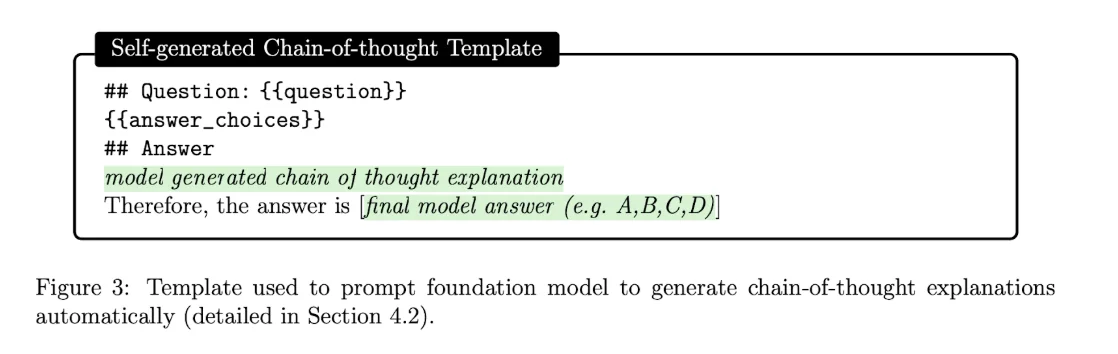

Self-Generated Chain of Thought (CoT): Use a simple prompt template to get the GPT-4 models to generate CoT examples for future few-shot example ICL training. Here’s an example prompt:

Dynamic Few-Shot Selection: During test-time, query the vector database by generating the same embedding for the unseen test questions, use k-means or a similar search model to identify the most similar few-shot CoT examples to provide as ICL examples for the model. This is essentially dynamically generating the few-shot examples for the model’s prompt. This entire process is almost completely automated.

Choice Shuffling Ensemble: They noticed the models tend to have some bias towards picking options in certain positions. So they used a classic CoT-SC type ensemble approach by asking the model to repeat the CoT prediction process m times (with temperature > 0) and choose the final answer by scoring the aggregate. Additionally, shuffle the order of the options for each run to further improve the randomness (apart from just temperature > 0).

The results were pretty convincing

Comparing MAD Strategies

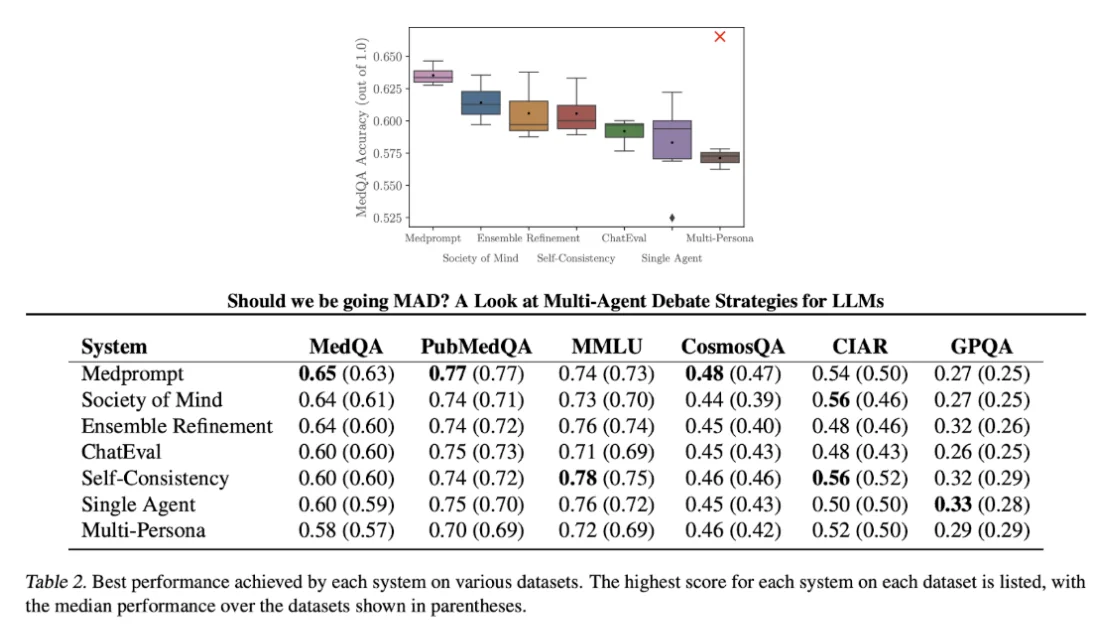

Should we be going MAD? A Look at Multi-Agent Debate Strategies for LLMs

This paper benchmarks several Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) strategies like Society of Minds, Multi-Persona, etc. against other single-agent prompting techniques like self-consistency, ensemble refinement, and Medprompt across a bunch of Q&A datasets (medical and reasoning). The main results from the paper are that:

MAD isn’t always better

Note the top-right corner X in the first diagram. Multi-persona was actually able to score the highest on that particular benchmark simply by tuning the degree to which the angel was asked to disagree with the devil. In short, MAD protocols seem a lot more sensitive to their ‘hyperparameters’ as compared to single-agent strategies. There is also some bias of LLMs towards their own responses in a mult-model multi-agent setup.

Tuning Can Greatly Affect Results

They introduced a concept of agreement modulation. They allowed ‘tuning’ the verbal prompt given to the multi-persona model by introducing a percentage into the prompt. Example:

“You should agree with the other agents 90% of the time.”

This actually made Multi-Persona go from being the lowest scoring strategy to the highest scoring strategy in that benchmark. But it also negatively affected its performance in a different benchmark. In benchmarks like CIAR, which was meant to be more counter-intuitive, higher percentages helped. And in more ‘straightforward’ benchmarks, lower numbers helped. The tuning factor was benchmark dependent.

The ‘winner’ is likely benchmark and use-case dependent. No single strategy dominated all the benchmarks. It’s important to have our own benchmark for our case and be able to experiment with it.

Finally, implementing complex LLM prompting / interaction patterns can get relatively complicated if done wrong. Classic software programming wasn’t quite built for handling probabilistic outputs and large dumps of prompt text in code. In this context, I find DSPy to be one of the best practical ways to implement agentic code. With DSPy you can almost quite go back to a “Program, don’t prompt.” mode of operation. If you found this interesting, check out my blog on Building a Type-Safe Tool Framework for LLMs in Scala for details on implementing such patterns yourself from scratch!