Parallelism With OMP

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

We learnt a bit about vectorization in Vectorization & Analyzing Loop Dependencies, we’ll now try to add more parallelism to our programs by leveraging more hardware features (multiple processing units / cores).

Processes vs Threads

Processes are independent of each other and work in completely sand boxed environments. They don’t share memory / any other resources and this makes it notoriously difficult to communicate among processes. Threads on the other hand are interdependent and share memory and other resources.

OpenMP

Easy quick and dirty way to parallelize your program. NOTE: OpenMP is not smart, and if you have dependencies which you attempt to parallelize you will segfault.

Primary advantages are that it works cross platform and independent of the number of cores on a machine. Disabling multi-threading effects is also as simple as omitting the -fopenmp flag.

Some useful info:

- Can use environment variables to limit number of threads code is parallelized over

export OMP_NUM_THREADS=x - Can use

#pragma omp parallel shared(A) private(B)to force OpenMP to treat certain variables as private data and ensure every thread has its own copy and keep certain variables data shared over multiple threads. NOTE: When variables are shared, their data is NOT accessed under mutex locks. Race conditions are very much possible.

Side note, compilers can analyze loops for dependencies and auto-parallelize code when possible. icc has the -parallel option and gcc has Graphite. https://gcc.gnu.org/wiki/Graphite

Static vs Dynamic thread scheduling & Thread affinity

The BLIS Library’s document on multi-threading provides a very comprehensive description of thread affinity and why it is important

This is important because when the operating system causes a thread to migrate from one core to another, the thread will typically leave behind the data it was using in the L1 and L2 caches. That data may not be present in the caches of the destination core. Once the thread resumes execution from the new core, it will experience a period of frequent cache misses as the data it was previously using is transmitted once again through the cache hierarchy. If migration happens frequently enough, it can pose a significant (and unnecessary) drag on performance. The solution to thread migration is setting processor affinity. In this context, affinity refers to the tendency for a thread to remain bound to a particular compute core. There are at least two ways to set affinity in OpenMP. The first way offers more control, but requires you to understand a bit about the processor topology and how core IDs are mapped to physical cores, while the second way is simpler but less powerful. Let’s start with an example. Suppose I have a two-socket system with a total of eight cores, four cores per socket. By setting

GOMP_CPU_AFFINITYas follows$ export GOMP_CPU_AFFINITY="0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7"I am communicating to OpenMP that the first thread to be created should be spawned on core 0, from which it should not migrate. The second thread to be created should be spawned on core 1, from which it should not migrate, and so forth. If socket 0 has cores 0-3 and socket 1 has 4-7, this would result in the first four threads on socket 0 and the second four threads on socket 1. (And if more than eight threads are spawned, the mapping wraps back around, staring from the beginning.) So with

GOMP_CPU_AFFINITY, you are doing more than just preventing threads from migrating once they are spawned–you are specifying the cores on which they will be spawned in the first place.Another example: Suppose the hardware numbers the cores alternatingly between sockets, such that socket 0 gets even-numbered cores and socket 1 gets odd-numbered cores. In such a scenario, you might want to use

GOMP_CPU_AFFINITYas follows$ export GOMP_CPU_AFFINITY="0 2 4 6 1 3 5 7"Because the first four entries are 0 2 4 6, threads 0-3 would be spawned on the first socket, since that is where cores 0, 2, 4, and 6 are located. Similarly, the subsequent 1 3 5 7 would cause threads 4-7 to be spawned on the second socket, since that is where cores 1, 3, 5, and 7 reside. Of course, setting

GOMP_CPU_AFFINITYin this way implies that BLIS benefits from this kind of grouping of threads–which, generally, it does. As a general rule, you should try to fill up a socket with one thread per core before moving to the next socket.A second method of specifying affinity is via

OMP_PROC_BIND, which is much simpler to set:$ export OMP_PROC_BIND=closeThis binds the threads close to the master thread, in contiguous “place” partitions. (There are other valid values aside from close.) Places are specified by another variable,

OMP_PLACES:$ export OMP_PLACES=coresThe cores value is most appropriate for BLIS since we usually want to ignore hardware threads (symmetric multi-threading, or “hyper-threading” on Intel systems) and instead map threads to physical cores.

Setting these two variables is often enough. However, it obviously does not offer the level of control that

GOMP_CPU_AFFINITYdoes. Sometimes, it takes some experimentation to determine whether a particular mapping is performing as expected. If multi-threaded performance on eight cores is only twice what it is observed of single-threaded performance, the affinity mapping may be to blame. But if performance is six or seven times higher than sequential execution, then the mapping you chose is probably working fine.Unfortunately, the topic of thread-to-core affinity is well beyond the scope of this document. (A web search will uncover many great resources discussing the use of

GOMP_CPU_AFFINITYandOMP_PROC_BIND.) It’s up to the user to determine an appropriate affinity mapping, and then choose your preferred method of expressing that mapping to the OpenMP implementation.

Processes vs Threads

One question to address before we begin using threads is asking “Why threads?” Processes are also capable of offering the same type of functionality that threads offer. Processes can also execute in parallel and work on different data at the same time. The reason why we prefer threads to processes is simple, communication. Processes by nature are completely isolated systems, which means they are in a sandboxed environment and inter-process communication is not easy. If there is some sort of accumulation variable whose task is split over multiple threads, it is much easier to do the final accumulation in a thread-based environment than with multiple processes. This is because threads share the same address space (code and data segments, registers, and stack segments are duplicated). To achieve the same level of ease of use with threads we would have to do something similar to mmaping a shared address space and manually managing it which is both a lot of extra effort and possibly has a higher overhead.

OMP (Again)

OMP is a highly customizable API and there are a lot many things that we can achieve with it.

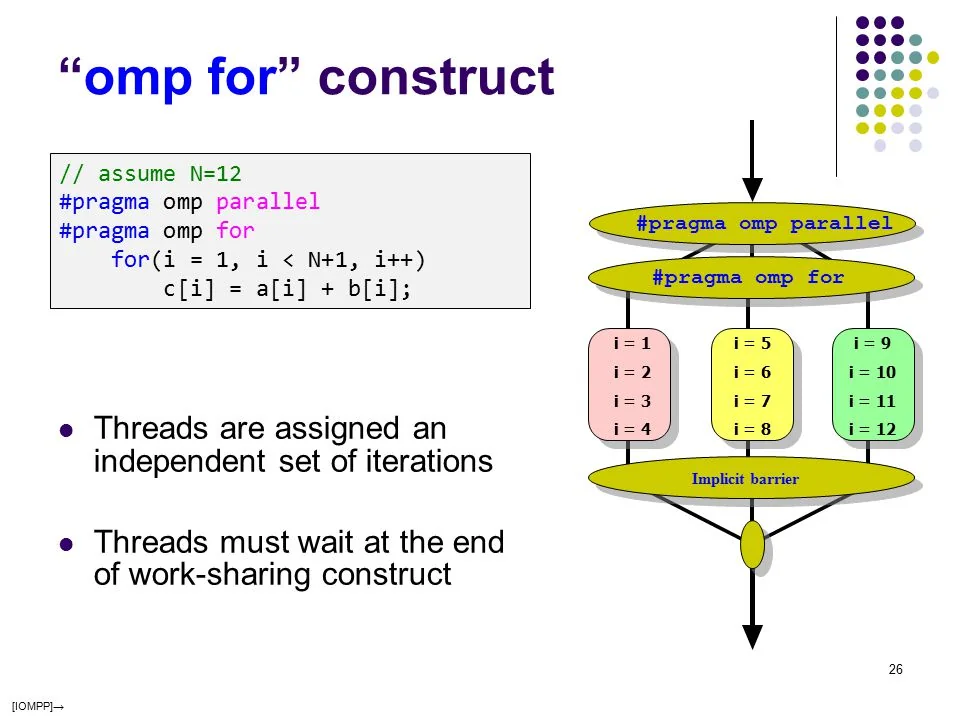

parallel & for

Two of the most commonly used and most basic pragmas to know are #pragma omp parallel and #pragma omp for. The parallel pragma simply makes a code block execute in parallel, whereas for is a pragma that instructs a parallel code block to divide the loop into multiple chunks and assign each one to a different thread associated with that pool.

// This instructs OMP to assign a thread worker group to the below code block

#pragma omp parallel

{

// This instructs the parent parallel block to split the for loop into chunks

// and assign each thread in the worker group a chunk to execute in parallel

#pragma omp for

for(int i=0; i<10; i++) printf("%d\\n", i);

}

The above code can also be compressed and written as a single pragma #pragma omp parallel for and put above a for loop.

Note, for is simply a directive that instructs the parallel pragma to execute something in parallel. Further, the extended syntax allows us to run other blocks of code in parallel with the for loop even and is a powerful construct to be aware of.

There are also a lot of modifiers that you can apply to the parallel pragma to control it’s behavior.

num_threads(n)This instructs OMP to allocate exactly

nthreads to the worker group associated with theparallelblock. The default is to associate one thread for each physical thread supported by your CPU. This can be useful to limit the number of threads generated.proc_bind(close/master/spread)Let’s say you were working on a NUMA architecture where the distances of threads from each other mattered.

spreadinstructs OMP to bind each virtual thread to physical threads that are as far away apart from each other as possible. This is useful when the threads are accessing memory unrelated to each other and you don’t want to end up with multiple threads pulling unrelated data into the cache and causing thrashing.mastermakes each virtual thread execute on the same physical thread.closeinstructs OMP to bind each virtual thread to physical threads that are close by each other. This is useful when the threads are accessing common data. Now both threads can pull in shared data into the cache and both might benefit from increased cache hit rates.

for also has some useful modifiers. In particular, schedule(guided/static/dynamic). The default option for for is static. This is best explained through an example.

Let’s say we had a for loop like so and a total of 4 threads on our machine.

#pragma omp parallel for

for(int i=0; i<16; i++) {

// S++

}

Let an asterisk * represent the work done in each iteration of the loop and let the threads associated with this block of code be 0, 1, 2, 3. This is how the work distribution across threads would look like.

Thread 0: ****

Thread 1: ****

Thread 3: ****

Thread 4: ****

Essentially, the loop is divided into chunks of $\frac{N}{staticsize}$ and each thread is allotted a chunk to compute. When $staticsize$ is not mentioned simply divides $N$ as uniformly as possible. Let’s say I used schedule(static 2). We would get work division like below:

Thread 0: ** **

Thread 1: ** **

Thread 2: ** **

Thread 3: ** **

Each thread is given $\frac{N}{staticsize}$ work to do and it is split up in a round-robin manner.

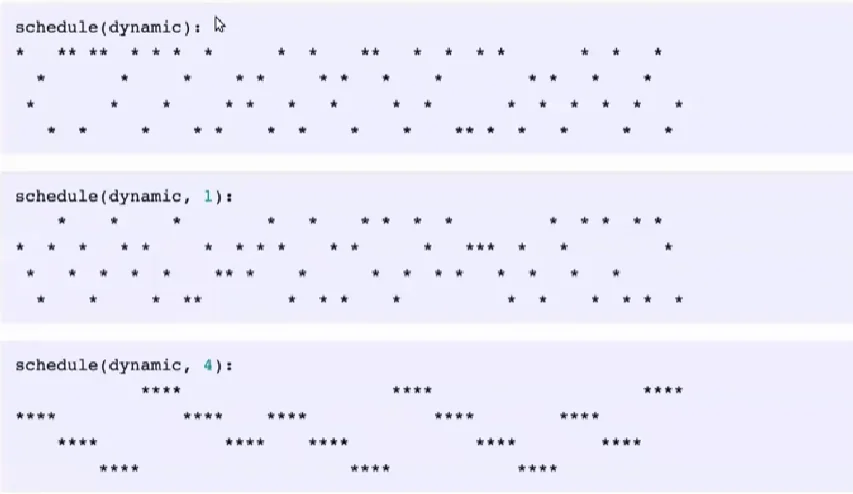

When we use dynamic, the work division looks like this:

If we’re working with data in a manner where preserving thread locality is crucial dynamic is a terrible choice, but

Take as an example the case where the time to complete an iteration grows linearly with the iteration number. If iteration space is divided statically between two threads the second one will have three times more work than the first one and hence for 2/3 of the compute time the first thread will be idle. Dynamic schedule introduces some additional overhead but in that particular case will lead to much better workload distribution. A special kind of

dynamicscheduling is theguidedwhere smaller and smaller iteration blocks are given to each task as the work progresses.

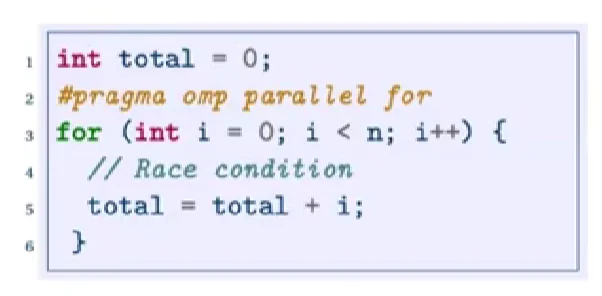

As mentioned before, OMP does not make your code magically thread safe.

This will not work as expected. To make specific lines of code execute atomically we can add the pragma #pragma omp atomic to instruct OMP that the next instruction must be executed atomically. To instruct OMP that an entire block of code must be executed atomically we can use the pragma #pragma omp critical on a code block.

However, let’s say we were trying to parallelize the summing of an array.

for(int i=0; i<n; i++) sum += arr[i];

If we parallelized this using atomic every iteration will release and acquire the lock and the code is hardly parallel anymore. For special types of operations like accumulation we can instead use

int sum = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:sum)

for(int i=0; i<n; i++)

sum += arr[i];

reduction has far lesser overhead than critical or atomic. It essentially instructs each thread to have its own accumulator and then finally sum up the accumulators (accumulate the accumulator) at the very end. This reduces the number of acquire/lock operations we have to perform to num_threads instead of $N$.

Execution model

In general, this is how OMP handles the parallel execution of code. However, OMP is pretty advanced and we can do async tasks as well using the task pragma. Instead of having to deal with an implicit barrier at every join after a fork, we can continue execution and only wait (#pragma omp taskwait) when we really need to wait for a dependency to finish computing.

References

These notes are quite old, and I wasn’t rigorously collecting references back then. If any of the content used above belongs to you or someone you know, please let me know, and I’ll attribute it accordingly.