Public Key Cryptography, Coming Up With RSA

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

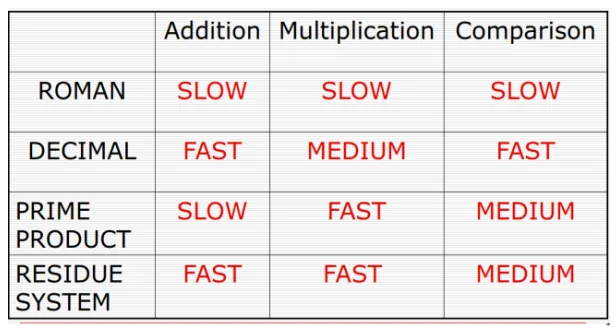

Mathematical operations across number systems

Why do we use the decimal number system? We as humans have been taught to count, add, subtract, multiply and divide all in the base 10 number system. We could’ve just as easily used binary, or maybe even roman numerals. But we chose 10. Why?

In fact, humans didn’t always use the decimal number system. Back in the day, counting began with something akin to tally marks. However, it was pretty much impossible to do much more than count small numbers. Working with large numbers meant we had to make a LOT of marks.

Eventually, this lead to the birth of roman numerals. But even this wasn’t great. It was very difficult to add and multiply numbers. Comparisons were not easy either. Over the evolution of number systems, at some point, we decided to settle on decimal because it provided a convenient representation to add and compare numbers in. Multiplication is still slow but not as bad as it was with Roman or the Tally systems.

A rough comparison of the different systems of representation.

I watched this video recently and I think it provides a great overview of how our choice of number systems came to be what it is and how they might change in the future.

Why We Might Use Different Numbers in the Future - Up and Atom

Our choice of number systems might change. If we find a different base that gives us something more, there’s a very good chance that we might indeed ditch the decimal number systems and switch to something else altogether.

2 cool number systems to consider are the base 8 and base 12 number systems.

Making multiplication faster?

Well, we might not change how fast computers are able to multiply two numbers, but what about humans?

Consider multiplying in base 10, we’re able to multiply numbers quickly because we remembered the times tables for the different numbers as kids. The easiest times tables to remember are the ones that are a factor of the base number. For decimal, we have easy 2 and 5 times tables.

This is intuitively understood from the fact that dividing 10 by those numbers gives us an integer. This has the overarching implication that their times tables follow a regular pattern that is easier to remember.

Consider octal (base 8) and duodecimal (base 12)

With octal, it has a smaller set of times tables and has the same number of factors. 2 and 4. Further, it gives us an additional property, simple halving of base. $\frac{8}{2} = 4 \text{ and } \frac{4}{2} = 2 \text{ and } \frac{2}{2} = 1$.

Duodecimal has a bigger times tables but has even more factors. 4! We have: 2, 3, 4 and 6. It also has better halving than decimal. $\frac{12}{2} = 6 \text{ and } \frac{6}{2} = 3$.

These simple properties might not make them any better to work with for computational purposes, but for humans, it might make handling different computations easier :)

Public Key Cryptography & RSA Encryption

So far we only talked about ways to make these operations faster, because in general, we always consider faster to be better. However, there is a field where making things slower is better. That is the field of public-key cryptography.

Let’s say we have 2 people Alice and Bob trying to communicate with each other. Most cryptography revolving around how they can securely send each other a message relies on the fact that they both had previously agreed upon a secret key. If this setup was possible, they could do something as simple as a Caesar cipher to encrypt the message. However, in many situations, it is not possible for Alice and Bob to previously agree upon such a key.

The public key cryptography problem is the problem of sending this key itself privately between Alice and Bob.

Diffie-Hellman key exchange is a well-known algorithm that proposes a great solution to this problem. It is theoretically nice to hear, but it relies on the fact that we can mathematically come up with a construct where we are able to generate a trapdoor function with the following properties.

- Let’s say Alice and Bob each get to keep a public key and a private key. $A_{public}, A_{private}, B_{public}, B_{private}$

- We want to have a method where we can encrypt a message using the public key quickly.

- But at the same time, the decryption process must be very slow using the public key.

- However, the decryption process must be very quick using the private key.

The trapdoor

We use the idea of modular inverse here to come up with a sound mathematical model of such a trapdoor function.

The slow operation

For our trapdoor to work, we need some operation that is extremely slow to compute. The operation that we will be looking at is the factorization of prime numbers. Integer prime factorization is a hard problem. There is no known polynomial-time algorithm that can factorize a number into its primes.

However, multiplying the factors to get the original number is easy.

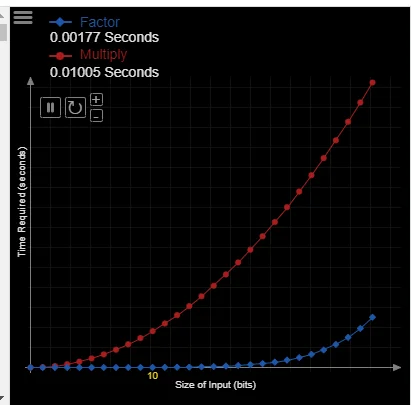

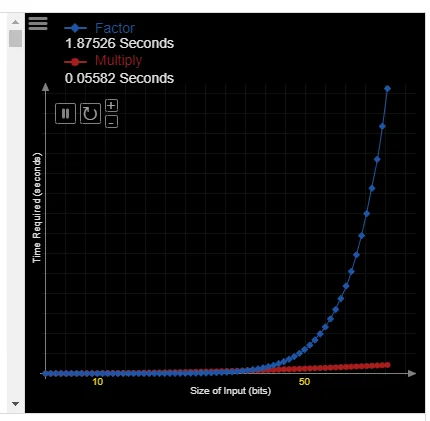

I found this visualization quite nice to understand the idea from.

For smaller inputs, integer prime factorization is quite fast. But with an increasing number of bits in the input, the algorithm shows its exponential complexity. It becomes pretty much unfeasible for any computational device that we have today to solve the problem in a reasonable amount of time. Notice that multiplication, however, remains quite fast.

Now, to understand the RSA algorithm better, it is important to have an understanding of Wilson’s Theorem, Fermat’s Little Theorem & Euler’s Totient Function. Once we have those tools to help us, we can build the rest of the devices we need to build our algorithm.

One last trapdoor

Let’s suppose we had some integer $m$ and we performed the following operation on it.

$$ m^e \ mod \ n \equiv c $$Notice that computing $c$ is easy. We can compute the above expression quickly using techniques like binary exponentiation. However, given just $c$, $n$ and $e$, it is very hard to compute $m$. Any algorithm that attempts to try this would have to perform a lot of trial and error.

Notice that there are no proofs for why these trapdoor functions are like so. If it can be proven that we can compute these “inverse” operations in polynomial time, we would be able to break the RSA encryption algorithm. The safety of RSA hinges on the hope that $P \neq NP$.

The RSA Algorithm

Now all that is left to do is to tie up these mathematical trapdoors we’ve constructed to an algorithm that can effectively solve the key exchange problem.

We will begin by demarcating the different variables used in the algorithm and the domain they are visible in.

Private domain:

- The private key $d$. This contains info about the prime factorization of $n$.

- The decoded message $m$.

Public domain:

- The public encryption key $E$, which consists of the following two things

- A public exponent $e$

- The product of two large primes $n$. Note that the factorization is not known in the public domain. Only the product is visible.

- The encrypted message $c$.

Note that the variables in the private domain are visible ONLY to their owner. They must never be sent in the public domain. Only the public encryption key and encoded message are sent in the public domain.

Working

Let’s suppose that Bob wants to send a secret message to Alice. The secret message here is represented by an integer $m$. Notice that because Alice’s encryption key is available in the public domain, Bob can use Alice’s encryption key to encrypt the message as follows.

Encryption

Bob performs the following operation to his message $m$ to encrypt it.

$$ m^e \ mod \ n \equiv c $$Sending the message

Bob now sends his encrypted message $c$ in the public domain. Notice that in the public domain, only the values of $c$, $e$ and $n$ are known. This is not enough to compute the value of $m$ easily. It is a hard problem and computationally not feasible to solve. Hence no potential attacker in the public domain can compromise / gain access to the secret message $m$.

Decoding

Once Alice has received the message $c$, she needs a fast way of computing back $m$. Recall that $n$ was the product of two huge primes and Alice knows the prime factorization of $n$. Now, she needs to somehow use this additional knowledge to quickly compute the inverse of the encryption. For this, we will go back to Euler. Notice that,

$$ \begin{aligned} m^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \ mod \ n \\ \implies m^{k\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \ mod \ n \\ \implies m\times m^{k\phi(n)} \equiv m \ mod \ n \\ \implies m^{k\phi(n) + 1} \equiv m \ mod \ n \end{aligned} $$Recall that Alice needed an easy way to get the inverse of the encryption that Bob performed. That is, if Bob raised $m^e$ to mod $c$, Alice needed an integer $d$ such that $(m^e)^d \ mod \ n \equiv m$.

Notice that this means that she needed $m^{e \times d} \equiv m \ mod \ n$. From the above-derived equation, we can see how the puzzle finally fits together.

If we set

$$ d = \frac{k \times \phi(n) + 1}{e} $$Notice that the value of $d$ depends on $\phi(n)$. And $\phi(n)$ is a hard problem to compute if the factorization of $n$ is unknown. Therefore, even if $n$ and $e$ are visible in the public domain, an attacker cannot compute $d$ as he/she cannot compute the value of $\phi(n)$ easily without knowing the prime factorization of $n$.

However, Alice knows the prime factorization of $n$! This means that she can compute and store the value of $d$ privately and use it to decode any encrypted message sent to her quickly.

And that’s it! We have an algorithm that solves the key exchange problem effectively by using the idea of modular inverse and number theory to generate trapdoor functions that allow us to construct this beautiful cryptography algorithm, RSA.

References

These notes are old and I did not rigorously horde references back then. If some part of this content is your’s or you know where it’s from then do reach out to me and I’ll update it.

- Professor Kannan Srinathan’s course on Algorithm Analysis & Design in IIIT-H

- Time Complexity (Exploration) - Khan Academy

- Why We Might Use Different Numbers in the Future - Up and Atom (Great Channel, recommend checking out)