Riemann Series Rearrangement

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Riemann Series Rearrangement

Take an arbitrary infinite sequence of real numbers $\left( a_1, a_2, a_3, \ldots \right)$ such that $\sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty a_n$ is conditionally convergent. Let $K$ be any number belonging to the set of the extended real numbers. Then there exists a permutation

$g: \mathbb{N}\to \mathbb{N}$ such that $\sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty a_{g(n)} = K$

Proof

Existence of a rearrangement that converges to a finite real number

Consider K to be any real positive number. Let the series be denoted by $S = \sum\limits_{i=0}^\infty a_i$. It is conditionally convergent. This means that it has an infinite number of positive and an infinite number of negative terms each. Let us denote them as follows:

Let $\left(p_1, p_2, p_3, \ldots\right)$ denote the sub-sequence of all positive terms in $S$ and $\left(n_1, n_2, n_3, \ldots\right)$ denote the sub-sequence of all negative terms in $S$. Since the series is conditionally convergent, both the positive and negative series $(p_i) \ \& \ (n_i)$ will diverge to $\pm\infty$. Hence, we have:

$$\sum{p} = +\infty$$$$\sum{n} = -\infty$$Since $\sum{p}$ tends to $\infty$, it implies that there exist a minimum natural number $N_1$ such that for all $N \geq N_1$ the following holds true: If $S_k$ denotes the partial sum of the first k terms of this rearranged series,

$$S_{N} = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N} p_i > K$$Since $N_1$ is the minimum such number, it implies that:

$$\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_1-1} p_i \leq K < \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_1} p_i$$We can begin to develop a mapping $\sigma : {\mathbb{N}}\to {\mathbb{N}}$ such that,

$$\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_1} p_i = \left( a_{\sigma(1)} + a_{\sigma(2)} + a_{\sigma(3)} + \cdots + a_{\sigma(N_1)} \right)$$Now, since $\sum n$ also diverges to $\infty$, it is possible to add just enough terms from $(n_i)$ so that the resulting sum

$$S_{N_1+M} = \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_1} p_i + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{M} n_i \leq K$$Let $M_1$ be the minimum number of terms required from $(n_i)$ for the above statement to hold true. This implies that,

$$\sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_1} p_i + \sum\limits_{i=1}^{M_1-1} n_i > K \geq S_{N_1+M_1}$$Consider equation (1), if we subtract $S_{N_1}$ from the inequality and flip the signs, we get:

$$0 \leq S_{N_1} - K < p_{N_1}$$In equation (2), if we subtract $S_{N_1+M_1}$ from the inequality, we get:

$$0 \leq K - S_{N_1+M_1} < -n_{M_1}$$Now, we can write $S_{N_1+M_1}$ as

$$S_{N_1+M_1} = a_{\sigma(1)} + a_{\sigma(2)} + a_{\sigma(3)} + \ \cdots \ + a_{\sigma(N_1)} + a_{\sigma(N_1+1)} + a_{\sigma(N_1+2)} + a_{\sigma(N_1+3)} + \ \cdots \ + a_{\sigma(N_1+M_1)}$$Notice, that this mapping of $\sigma$ is injective. Now, we can repeat the process we performed above. Add just enough positive terms from $\sum p$ till the partial sum of this new rearranged series is just greater than K, then add enough negative terms from $\sum n$ till the partial sum is lesser than or equal to K. Because both $\sum n \ \& \ \sum p$ diverge to infinity, this process can be carried out infinitely many times.

In general, our rearranged series would look like

$$p_1 + p_2 + \cdots + p_{N_1} + n_1 + n_2 + \cdots + n_{M_1} + p_{N_1+1} + p_{N_1+2} + \cdots + p_{N_2} + n_{M_1+1} + n_{M_1+2} \cdots + n_{M_2} + \ldots$$Note that for every partial sum who’s last summation step was adding terms from the positive series,

$$S_{p_i} - K < p_{N_i}$$and for every partial sum who’s last summation step was adding terms from the negative series,

$$K - S_{n_i} < n_{M_i}$$More generally, we can say that at every “change in direction” or magnitude, the partial sum of the rearranged series at that point differs from our real number K by at most $|p_{N_i}|$ or $|n_{M_i}|$. But we know that $\sum\limits_{i=n}^{\infty} a_n$ converges. Therefore, as $n$ tends to $\infty$, $a_n$ also tends to 0. Consequentially, $|p_{N_i}|$ & $|n_{M_i}|$ must also tend to 0. From the above two observations, we can say that the following is true:

As $n$ tends to $\infty$, the partial sums of our rearranged series $\sum a_{\sigma(n)}$ tends to K.

$$\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{\sigma(n)} = K$$This same method can be used to show convergence to any negative real number K or K = 0.

Existence of A Rearrangement That Diverges to Infinity

Let the series be denoted by $S = \sum\limits_{i=0}^\infty a_i$. It is conditionally convergent. This means that it has an infinite number of positive and an infinite number of negative terms each. Let us denote them as follows:

Let $\left(p_1, p_2, p_3, \ldots\right)$ denote the sub-sequence of all positive terms in $S$ and $\left(n_1, n_2, n_3, \ldots\right)$ denote the sub-sequence of all negative terms in $S$. Since the series is conditionally convergent, both the positive and negative series $(p_i) \ \& \ (n_i)$ will diverge to $\pm\infty$. Hence, we have:

$$\sum{p} = +\infty$$$$\sum{n} = -\infty$$Since $\sum{p}$ tends to $\infty$, it implies that there exist a minimum natural number $N_1$ such that for all $N \geq N_1$ the following holds true:

$$ \sum\limits_{i=1}^{N_1} p_i > |n_1| + c$$Where c is some constant positive real number. Similarly we can find a $N_2$ such that it is the smallest natural number for which the following holds true:

$$ \sum\limits_{i=N_1+1}^{N_2} p_i > |n_2| + c $$We can do this repeatedly an infinite number of times because the sub-sequence of positive terms diverges. This gives us our rearranged series:

$$\sum\limits_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{\sigma(n)} = p_1 + p_2 + \cdots + p_{N_1} + n_1 + p_{N_1+1} + p_{N_1 + 2} + \cdots p_{N_2} + n_2 + p_{N_2 + 1} + \ldots$$Owing to the way we chose $N_1$, the first $N_1 + 1$ terms of the series have a partial sum that is at least $c$ and no partial sum in this group is negative. Similarly, the partial sum of the first $N_2 + 1$ terms of this series are at least greater than $2c$ and no partial sum in this group is negative. In general, for any $N_i + 1$ terms of this series, we can say that the partial sum is at least $N_i*c$ and no partial sum in that group is negative. Hence, we can say that as n tends to $\infty$, $N_i$ tends to $\infty$ and therefore, the sequence of partial sums of the series tends to $\infty$.

Code to Analyze Series Rearrangement!

All programs related to this post can be found here: Repository Link.

From the proof, we can observe the algorithm one can use to rearrange a conditionally convergent series to sum up to any such real number K. Here, we will attempt to do two things.

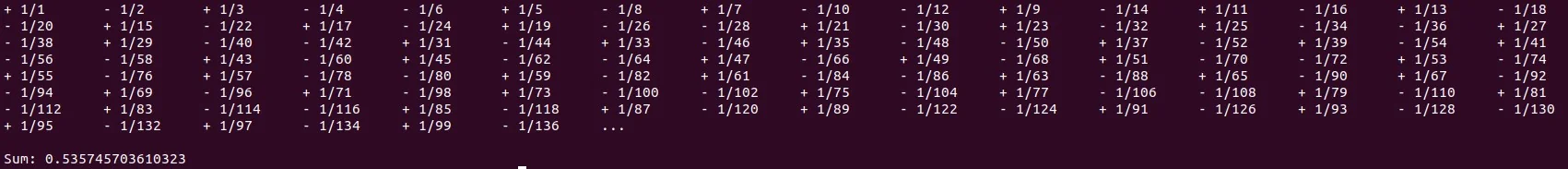

We will observe how the rearranged series looks like for it to converge to some real number M. You can use the programs in the above repo to print the series up to a certain number of terms for any real number M. Here, we will attach the output for what the beginning of the series looks like when we attempt to rearrange it to sum to 0.534.

We run the program like so: ./print_rearrangement 0.535 100 100\

The program will print what the series looks like for the first 100 groups of positive and negative terms.

Further, we can use prog1.cpp and prog2.cpp to generate data points for plotting. prog1.c will generate data points of the partial sums of the alternating harmonic series up to a given number of terms. We can use prog2.c to generate data points of the partial sums for a rearranged alternating harmonic series that converges to some given real number M.

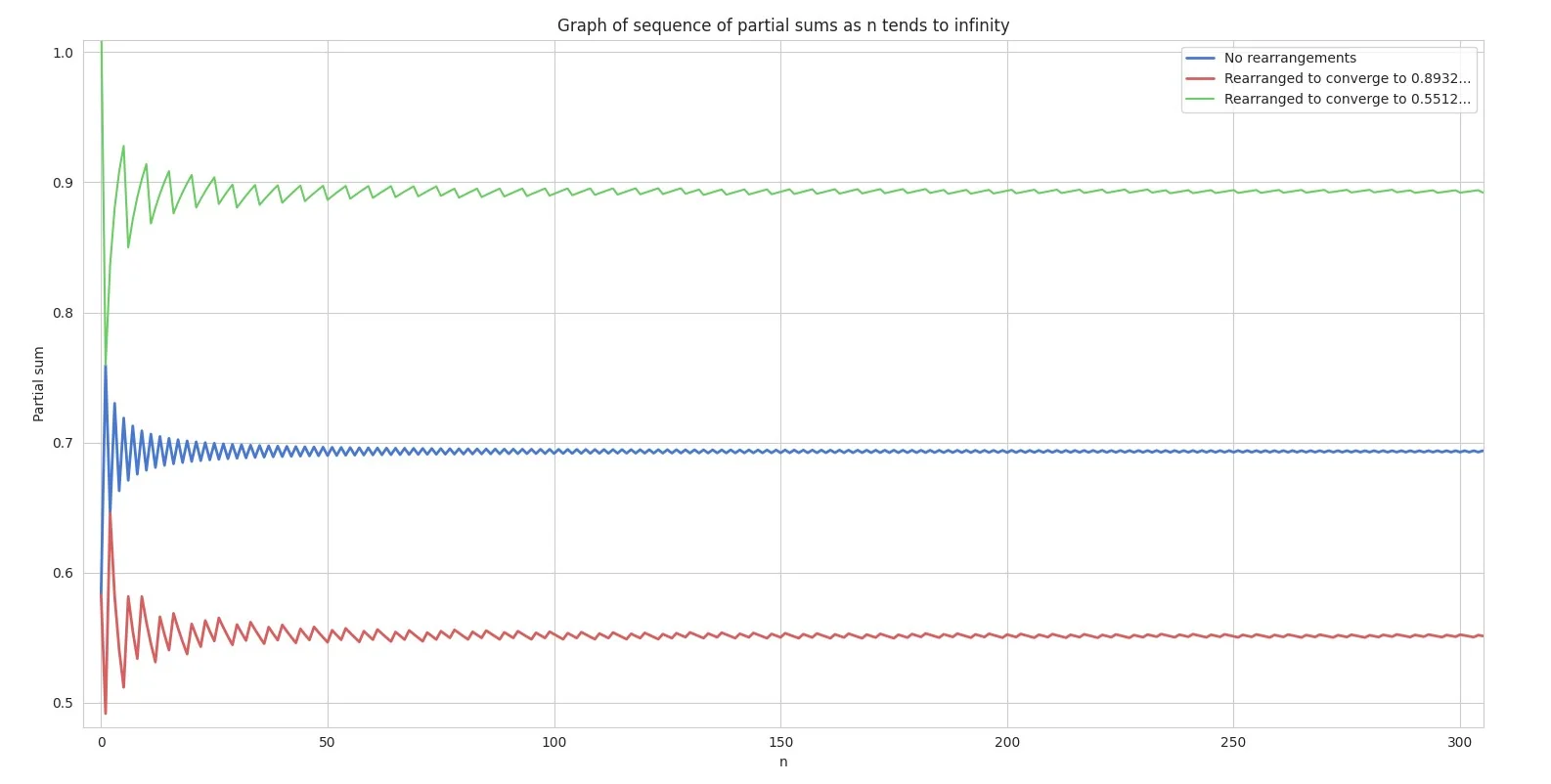

For the sake of illustration, we have chosen to plot the partial sums as n keeps increasing for the following rearrangements.

The normal alternating harmonic series

A rearrangement of the alternating harmonic series that sums to 0.5512

A rearrangement of the alternating harmonic series that sums to 0.8932

Plotting them gives us the below graph.

Hopefully, this graph is able to paint more intuition as to why rearranging the terms of an infinite conditionally convergent series changes its sum. By rearranging the terms such that the sequence of its partial sums oscillates around a limit of our choice, we’re able to effectively choose the limit we wish the sequence of partial sums to approach. This is due to the fact that the sum of the positive and negative terms individually diverge to infinity. But the series itself converges to some limit, hence the $n^{th}$ term of the series approaches 0.

Both these properties are true for conditionally convergent series and it is due to this very reason that we’re able to rearrange the infinite sum to converge to whatsoever real sum of our choice.