Set Cover & Approximation Algorithms

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Greedy (cont.)

We previously discussed how the greedy strategy to solving problems is often the best way to solve a problem (More Greedy Algorithms! Kruskal’s & Disjoint Set Union, Activity Selection & Huffman Encoding). It, almost always, provides a very simple implementation of an algorithm which is also very efficient. This is because we are able to reduce the overarching problem to a simple local problem that we can solve quickly at every step. This makes it a great solution when it works.

However, as is the case with all things that appear amazing, not all problems can be broken down be solved for a local optimum which restructures the problem into smaller versions of itself.

Greedy algorithms can also often trick the person into believing that they are right. This is because it appears to always do “the right” thing. Often changes taken locally affect the global optimum. They are enticing but often not optimal. Hence it is quite important for an algorithm analyst to ensure that his greedy strategy is indeed optimal and avoid getting baited.

Use as approximation algorithms

That said, greedy algorithms often give us a very good answer. The answer may not be optimal, but it gives us a “decent” approximation of the answer for an average case. This is somewhat intuitively understood from the fact that since the greedy is taking the optimal path at every step, it should at least give a decent result. While this is also the reason for it baiting people into believing it is optimal, it is also a good approximation algorithm and comes in clutch when we are tasked with hard problems.

Consider the set of NP-Complete problems. The Set Cover problem belongs to the set of NP-Complete problems. This means that it is one of the hardest problems to solve in NP. There exists no polynomial-time algorithm to solve Set Cover deterministically. (At least, as of now.)

Computers take a long long long time to solve NP-Complete problems. It is not feasible to expect a computer to solve the set cover problem for n > 100000 anytime in a few hundred years even. However, Set Cover is a common problem, and solving it could be very useful to us.

- Solving Sudoku can be reduced to an exact cover problem

- Companies (ex: airlines) trying to plan personnel shifts, often find themselves tasked with solving this exact problem

- Many tiling problems and fuzz-testing of programs also need to solve set cover

- Determining the fewest locations to place Wi-Fi routers to cover the entire campus

But it is not physically feasible for a computer to solve Set Cover. In cases like these, we turn to our savior, the enticing greedy algorithms. The greedy solutions for this problem are not optimal. But they run quickly and in most cases, provide a “close-to-optimal” answer.

Because the strategy is not optimal and relies on picking the local optimum, it is obviously going to be possible to reverse engineer a test case against our greedy which makes it often output a not-very-optimal answer, but the point is, in the real world, we have a high probability of not facing such specific cases. This makes them a great solution to our problem.

The Set Cover Problem

We mentioned why the set cover problem is useful & said that it belonged to the NP-Complete set of problems. But we never stated the problem formally. The Set Cover problem asks the following question, Given a set of elements $U$(called the universe) and a collection $S$ of $m$ sets whose union equals the universe, the set cover problem is to identify the smallest sub-collection of $S$ whose union is the universe $U$

The brute force for this problem is $O(m^n)$. Since this is not feasible to compute, let us consider greedy approximations.

A greedy approximation algorithm

An intuitive greedy that comes to mind is the following, “at every local step, pick the set which covers the most uncovered elements in the universe.” This intuitively makes sense because we are trying to pick the set $s_i$ which contributes the most towards completing the set cover. However note that this is not optimal and it can, in fact, be tricked into picking the wrong solution at every step.

Code & Complexity

The following code snippet is a C++ implementation of the greedy algorithm. Let’s try to put a bound on the complexity.

- The initial sorting step takes $O(nlogn) + [O(|s_1|log|s_1|)+\dots+O(|s_m|log|s_m|)]$

- The outer while loop may run as many as $O(n)$ iterations in the worst case. (Consider all disjoint singleton sets)

- The loop inside may run as many as $O(m)$ iterations

- Finally, applying two pointers on these strings will again take linear time. We can write this as $O(max\{|s_1|, \dots, |s_m|\})$.

- The loop inside may run as many as $O(m)$ iterations

The dominant term in this definitely comes from the nested while loop and not the sorting. Discarding the complexity from sorting and focusing on the loop, we see that the total complexity is

$O(nm*max\{|s_1|,\dots, |s_m|\})$

In general, we can say the greedy runs in cubic time complexity. This is a huge improvement from our NP-Hard $O(m^n)$.

// Input

string U = "adehilnorstu";

vector<string> S = {"arid", "dash", "drain", "heard", "lost", "nose", "shun", "slate", "snare", "thread", "lid", "roast"};

// Sort to allow 2 pointers later

sort(U.begin(), U.end());

for(auto &s:S) sort(s.begin(), s.end());

int left = U.size();

int ans = 0;

// The brute force loop

while(left){

int max_covered = 0;

int best_pick = -1;

// Go through all subsets of S and pick best one

for(int i=0, covered=0; i<S.size(); i++){

// Do two pointers to count new elements we are covering

for(int j=0, k=0; j<S[i].size() && k<U.size(); j++){

if(S[i][j]==U[k]) covered++, k++;

else k++, j--;

}

// Update pick choice

if(covered>max_covered) best_pick = i;

max_covered = max(max_covered, covered);

}

// Cleanup / Updates. Unimportant

ans++;

string new_string;

set<char> temp; for(auto &c:S[best_pick]) temp.insert(c);

for(auto &c:U) if(temp.find(c)==temp.end()) new_string += c;

swap(U, new_string); left = U.size();

}

cout<<ans<<endl;

Tricking the greedy

However, since greedy is not optimal, we can trick it into always giving the wrong answer.

Consider this following case,

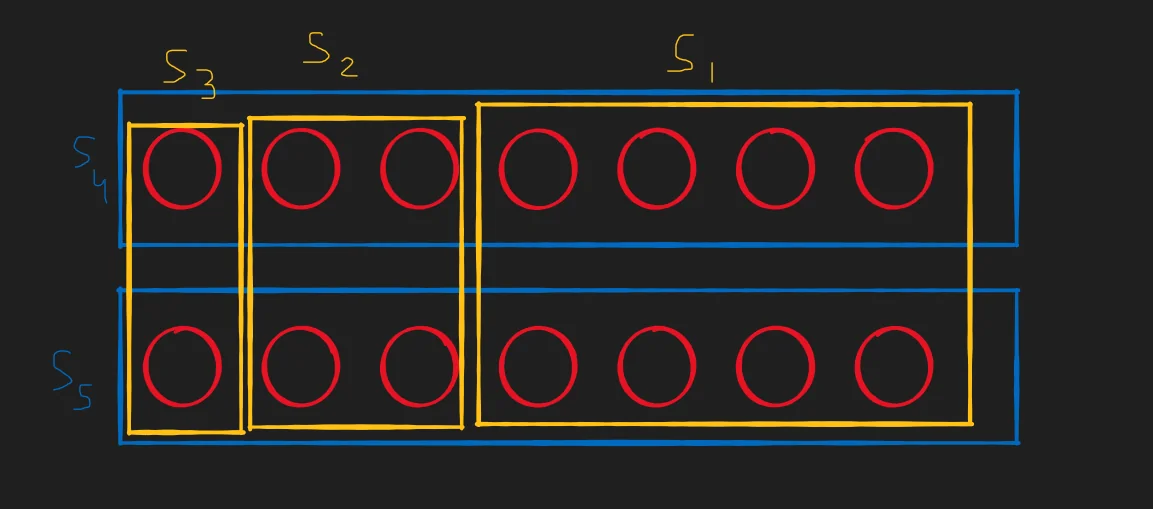

Our greedy strategy will end up picking $\{ s_1, s_2, s_3 \}$ while the optimal answer is actually $\{ s_4, s_5 \}$. Notice that this logic for “hacking” the algorithm can be extended to work for any power of 2 $\geq 3$

This isn’t a very specifically tailored case and something we might even end up finding in real life. This is a little worrying and naturally raises the question, “What is the worst approximation that the algorithm can give?”

This might seem a little difficult to put a bound on, but it is possible to do so with just one key observation.

Putting a bound on the approximation

Let’s suppose that our universe set is $U$ and we are attempting to cover $U$ using the $n$ sets belonging to the collection $B$.

Now, let us suppose that we know the optimal answer beforehand. Let this optimal answer be $k$. This means that we can always pick some $k$ sets from $B$ such that $\cup_{b_i}^k = U$.

Now, following along with the greedy strategy, we know that there will be a certain number of elements left uncovered after the $t^{th}$ iteration. Let’s call this number $n_t$. In the beginning, the entire set is uncovered, and hence $n_0 = 0$.

The pigeonhole principle states that if $n$ items are put into $m$ containers, with $n\gt m$, then at least one container must contain more than one item.

Note that at the $t^{th}$ iteration, if we have $n_t$ elements left and the optimal answer is $k$, then by the pigeon hole principle, there must be a set that has not been picked yet that can at least cover $\frac{n_t}{k}$

elements. This is the key observation which we can use to bound our approximation strategy. Our greedy will (by definition) pick the largest such set which covers $\geq \frac{n_t}{k}$ elements. This lets us put the following bound,

$$ n_{t+1}\leq n_t - \frac{n_t}{k} = n_t . \left( 1-\frac{1}{k} \right) \\ \implies n_t \leq n_0 \left(1-\frac{1}{k}\right)^t \\ \text{Now, } 1-x\leq e^{-x} \text{ and this equality only holds for } x=0\\ \implies n_t \leq n_0\left(1-\frac{1}{k}\right)^t \lt n_0(e^\frac{-1}{k})^t=ne^{\frac{-t}{k}} $$Further, if we substitute $t = k \ ln(n)$

$$ n_t \lt ne^\frac{-t}{k} = ne^{\frac{-k\ ln(n)}{k}} \\ = ne^{-ln(n)} = ne^{ln(\frac{1}{n})} = n.\frac{1}{n} = 1 $$Note that $n_t$ is the number of elements left at the $i^{th}$ iteration. Therefore it must be a non-negative integer $\lt 1$. The only possible answer is 0. When $n_t=0$, notice that the set has been completely covered and we have our answer.

This must mean that the algorithm will terminate after $t=k\ ln(n)$ iterations. Our algorithm picks exactly 1 set per iteration. This also implies that if our optimal answer is $k$, our greedy strategy will pick at most $k \ ln(n)$ sets. Hence we have successfully managed to put a bound on the approximation.

References

These notes are old and I did not rigorously horde references back then. If some part of this content is your’s or you know where it’s from then do reach out to me and I’ll update it.

- Professor Kannan Srinathan’s course on Algorithm Analysis & Design in IIIT-H