Shortest Common Superstring & De Brujin Graphs

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Preface & References

I document topics I’ve discovered and my exploration of these topics while following the course, Algorithms for DNA Sequencing, by John Hopkins University on Coursera. The course is taken by two instructors Ben Langmead and Jacob Pritt.

We will study the fundamental ideas, techniques, and data structures needed to analyze DNA sequencing data. In order to put these and related concepts into practice, we will combine what we learn with our programming expertise. Real genome sequences and real sequencing data will be used in our study. We will use Boyer-Moore to enhance naïve precise matching. We then learn indexing, preprocessing, grouping and ordering in indexing, K-mers, k-mer indices and to solve the approximate matching problem. Finally, we will discuss solving the alignment problem and explore interesting topics such as De Brujin Graphs, Eulerian walks and the Shortest common super-string problem.

Along the way, I document content I’ve read about while exploring related topics such as suffix string structures and relations to my research work on the STAR aligner.

Shortest Common Superstring (SCP)

We will now attempt to model the assembly problem (De-Novo Assembly & Overlap Graphs) as computational problems. Our first attempt at this will be modelling it as solving the SCP problem.

A shortest common superstring is a string that is a combination of two or more strings, such that the resulting string is the shortest possible string that contains all of the original strings as sub-strings.

The problem of finding the shortest common superstring of these sequences is equivalent to finding the original genome sequence, as it is the shortest possible sequence that contains all of the original sequences as sub-strings. Thus, solving the shortest common superstring problem can be used to assemble a genome from a set of overlapping DNA sequences. However, a sad reality is that this problem is NP-Complete.

Proof sketch: The shortest common superstring problem is NP-Complete because it is a generalization of the NP-Complete Shortest Hamiltonian Path problem. In the Hamiltonian Path problem, we are given a graph and must find a path that visits every vertex exactly once. To reduce the Hamiltonian Path problem to the shortest common superstring problem, we can represent the graph as a set of strings, where each string corresponds to a vertex in the graph. We can then create a new string for each possible path in the graph by concatenating the corresponding strings in the order that they appear in the path. The resulting set of strings will contain all possible paths in the graph as sub-strings. Finally, we can find the shortest common superstring of these strings, which will be the shortest possible path that visits every vertex in the graph exactly once. Because the shortest common superstring problem is at least as hard as the Shortest Hamiltonian Path problem, it is NP-Complete.

Greedy Approach

A greedy approach to solving the shortest common superstring problem involves iteratively selecting the pair of strings that overlap the most, and merging them into a single string. This process is repeated until all of the strings have been merged into a single superstring. It selects the pair of strings that appears to be the best choice without considering the overall optimality of the solution. This can give us a decent reconstruction but is sadly still pretty inaccurate in practice.

3rd Law of Assembly: Repeats Are Bad

This is probably the most frustrating problem in genome assembly and what makes it pretty much impossible to solve the assembly problem with $100\%$ certainty.

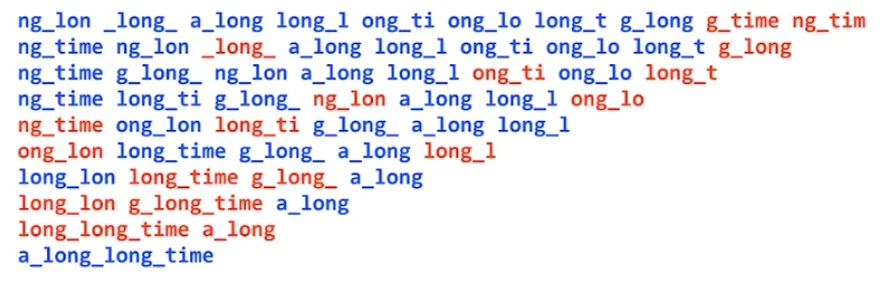

Consider the following example,

Our greedy solution gave us a shorter sequence than the original genome, this is due to the presence of overlapping reads from a repeating portion of our genome which is extremely hard to unambigiously solve. The primary problem here is that we are aware of its existence due to the pieced together multiple reads but we are not sure about the frequency of these repeats.

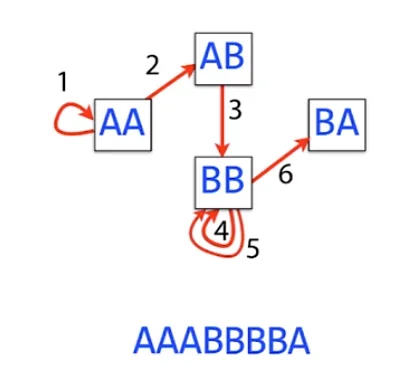

De Brujin Graphs

De Bruijn graphs are a mathematical construct that is often used in the field of computational biology, particularly in the context of genome assembly. In a De Bruijn graph, each vertex represents a k-mer, which is a sub-sequence of length $k$ from a given string. Edges in the graph represent overlaps between k-mers, such that two vertices are connected by an edge if the corresponding k-mers overlap by $k-1$ bases. The graph can then be used to efficiently represent the overlaps between the k-mers in the original string, and can be used to reconstruct the original string by finding a path through the graph that visits every vertex exactly once. This is also called an Eulerian Walk.

It has exactly one node per distinct k-mer and one edge per each k-mer.

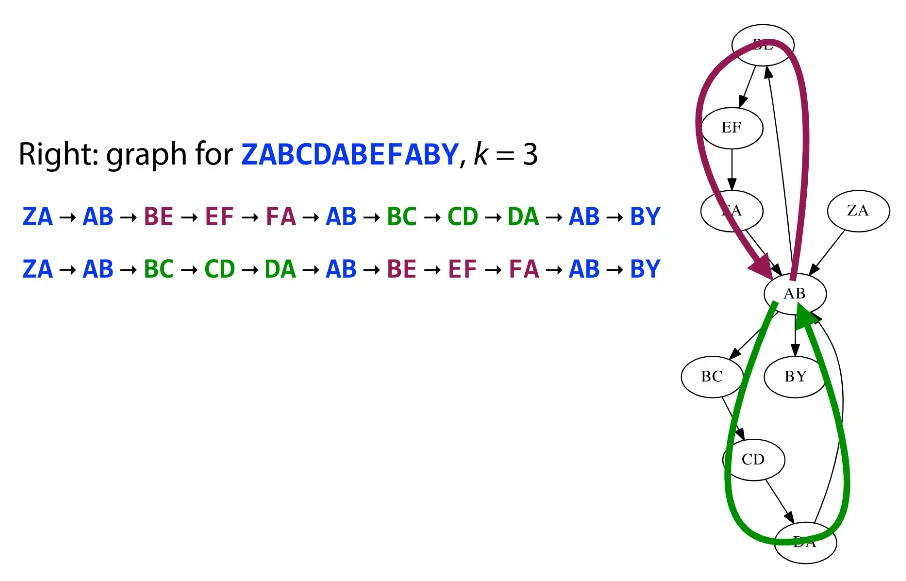

However, we have still not dealt with the problem of repeats. For example, if the graph contains multiple cycles, then it may not be possible to find an Eulerian walk that correctly reconstructs the original genome sequence, as the path may not be able to distinguish between the different cycles. Additionally, if the graph contains errors or missing k-mers, then an Eulerian walk may not be able to correctly reconstruct the original genome. This is all mainly caused due to the presence of repeats in the original genome.

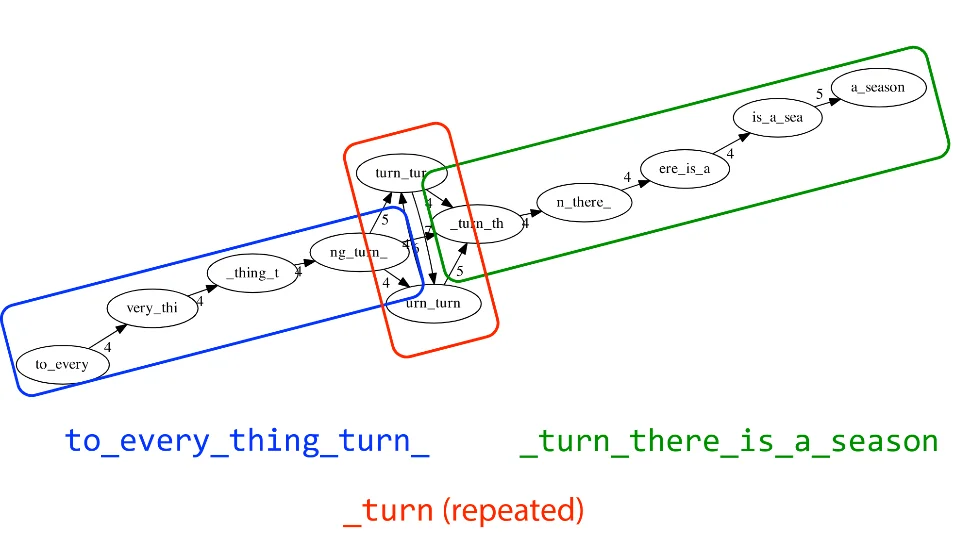

The issue in the above example occurs primarily due to the repeating term AB. This gives us multiple reshuffles of the sequence and we cannot deterministically figure out which reconstruction is correct.

Fixing What We Can

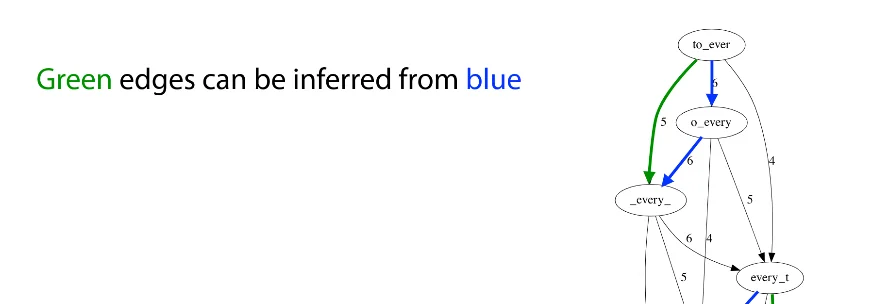

We often have edges like these showing up in the De Brujin graph where the existence of the blue edges nullify any information we might gain from the green edge. We can prune these from the graph.

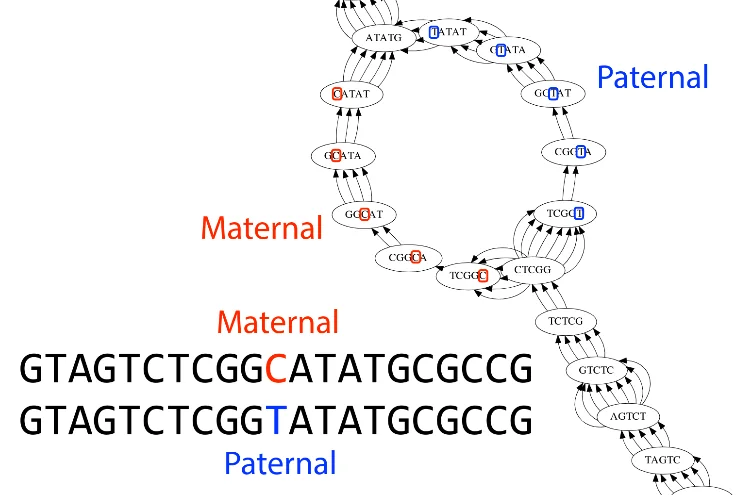

Maternal / Paternal chromosomes can have one different base in a read causing cycles like these to form. We can attempt to prune these from the graph as well.

Because repeats always cause ambiguity, we can attempt to break up the graph into parts and solve only the deterministic chunks first and mark the chunks with repeats as ambiguous. In fact, this is how most assemblers work in practice nowadays. Excluding small genomes, it is very difficult to get accurate reconstructions of a complete genome. Even the Human Genome, the most widely studied genome on the planet still has many gaps in it today due to the uncertainties caused by repeats in the genome.

Attempts at Discerning the Ambiguity

One simple solution we could provide here is not from a computational point of view but from the point of view of the technology that generates the sequences. Increasing the lengths of the reads could allow the repeating fragments to also contain some potion of distinct / unique read fragments which allows them to now be uniquely matched with better certainty. Another type of sequencing which gathers some metadata from the surrounding reads is also making it’s way into the mainstream. In the end, we’ll need to get more data than we already have and then develop algorithms to solve these new problems with the additional metadata to try to get better certainty about the ambiguous portions of sequenced Genomes.