Smart Pointers

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Resources referred to:

- SMART POINTERS in C++ (std::unique_ptr, std::shared_ptr, std::weak_ptr) - The Cherno

- Back to Basics: Smart Pointers and RAII - Inbal Levi - CppCon 2021

- Back to Basics: C++ Smart Pointers - David Olsen - CppCon 2022

Before reading this section, I recommend reading the previous section on new and delete to get a better idea of the problem(s) we have with memory allocation and manipulation and how we’re trying to fix them. We figured out how to workaround / solve the uninitialized memory problem, but we still have to deal with the issue of memory leaks and dangling pointers.

Preface

As programmers, when working in a large code base, it is often difficult to manually keep track of all the memory allocations and remember to free them correctly. Tools like valgrind can help identify memory leaks, but it’s still a pain to run a massive project on it. Even worse, sometimes programmers are just too lazy to free memory correctly.

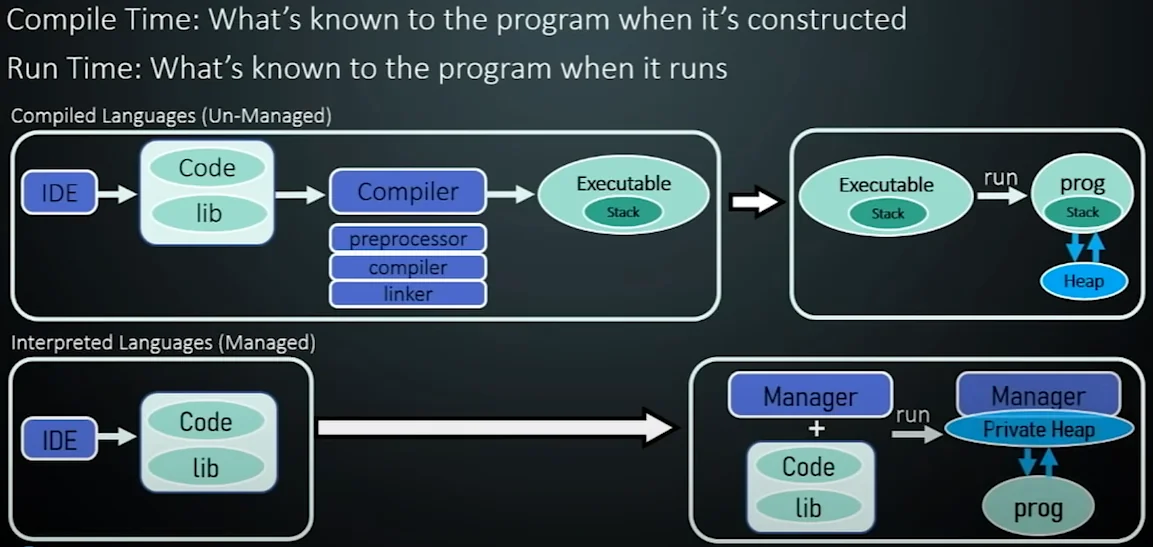

Java and other more “modern” languages have the idea of keeping garbage collectors. Its primary purpose is to automatically manage memory by identifying and reclaiming memory that is no longer needed or accessible by the program, thus preventing memory leaks and ensuring efficient memory usage. However, the existence of a garbage collector means that the program can only be run on a system on a runtime. For Java, this would be the JVM. This introduces a performance overhead because the garbage collector is a tool that is actively working in the background to identify unreachable objects and freeing them. Being C++ nerds, we don’t want performance bottlenecks.

Instead, the goal for C++ is to introduce an “API” of sorts that programmers can use to manage their memory right. Smart pointers are a cool interface provided by the C++ standard library to leverage the power of runtime stack allocation to manage memory efficiently by automating the process of calling new and delete. In essence, smart pointers are just simple wrappers around raw pointers.

The ownership model

The way C++ tries to solve the automatic memory management problem is by introducing the ownership model. Smart pointers enforce this model for dynamically allocated heap memory.

std::unique_ptr=> Represents a “single owner” model. Memory managed by anstd::unique_ptrcan only “be owned by” by that one instance of an unique pointer. It cannot be owned (copied) by multiple unique pointer instances. The only way to change ownership is to move the ownership to a different instance of an unique pointer. Original pointer releases, new pointer acquires.std::shared_ptr=> This builds on the unique pointer by now allowing a resource to be shared / “owned” by multiplestd::shared_ptrinstances. Multiple shared pointers can now share and copy the ownership rights over a shared pointer. The memory being managed is freed only when every last owner of the shared pointer has gone out of scope.std::weak_ptr=> This is a weaker version of the shared pointer. Weak pointers can copy / gain weak ownership over a shared pointer. This means that it does have strong ownership rights. If the strong owners go out of scope, the weak pointer will be invalidated. In essence, it does not hold any power over when the pointer may be invalidated / cleaned up.

std::unique_ptr

An unique_ptr is perhaps the simplest type of a smart pointer. It’s a scoped object, which just means that when the pointer goes out of scope, it gets destroyed. Unique pointers are called unique pointers because you cannot copy an unique pointer. Why? Because all an unique pointer really is, is just a class wrapper around your raw pointer. If it was copied, we would now have 2 instances of this manager class. When they go out of scope, we call the destructor twice, the second one attempting to free a nullptr.

// My sample simple implementation of an unique_ptr

template<typename T>

class unique_ptr{

public:

explicit unique_ptr() : obj(nullptr) {}

explicit unique_ptr(T* obj) : obj(obj) {}

explicit unique_ptr(unique_ptr &other) = delete;

~unique_ptr() { delete obj; }

private:

T* obj;

};

Let’s go back to our toy-class Entity (from new and delete) and see how it works now:

std::unique_ptr<Entity> oobj(new Entity); // Output: Constructor!\nDestructor!\n

unique_ptr<Entity> fobj(new Entity); // Output: Constructor!\nDestructor!\n

Note that the explicit constructors and deleted copy-constructors means that the following code will not compile.

std::unique_ptr<Entity> obj = new Entity;

conversion from ‘Entity*’ to non-scalar type ‘std::unique_ptr<Entity>’ requested

### `std::make_unique`

The ‘recommended’ way to initialize an unique pointer in C++ is using std::make_unique<T>. The primary reason this is recommended is because of exception safety. If the constructor happens to throw an exception we’ll now not end up with a memory leak or dangling pointer. make_unique is basically a way to shorten writing:

// allocation. `new` can throw an exception if constructor fails.

Entity *b = new Entity("42");

// Handle the memory to unique_ptr to manage the memory

std::unique_ptr<Entity> uptr(b);

// OR do both in one-step with std::make_unique

std::unique_ptr<Entity> uptr = std::make_unique<Entity>("42");

Here is an example where this exception safety is of good use:

// unsafe

foo(std::unique_ptr<int>(new int(4)), std::unique_ptr<int>(new int(2)));

// safe

foo(std::make_unique<int>(4), std::make_unique<int>(4));

In the first example, first of all we have no guarantee of order of evaluation. From cppreference.com:

Order of evaluation of any part of any expression, including order of evaluation of function arguments is unspecified (with some exceptions listed below). The compiler can evaluate operands and other sub-expressions in any order, and may choose another order when the same expression is evaluated again.

When an exception is thrown and control passes from a try block to a handler, the C++ run time calls destructors for all automatic objects constructed since the beginning of the try block. This process is called stack unwinding. The automatic objects are destroyed in reverse order of their construction.

Say the 2nd one throws an exception in the constructor, its guarding destructor will not be called and we’ll be left with a memory leak. Because order of evaluation is not guaranteed we can’t even easily determine the leak.

Coming back to unique pointers, we know that it is unique because the copy and copy-assignment constructors have been deleted and that the memory gets freed only when the destructor is called. Not true! There are 4 cases when the memory that is managed by a shared pointer can be freed.

- When the object goes out of scope

- When we

movea resource from one unique pointer to another

auto e1 = std::make_unique<Entity>("abcd");

auto e2 = std::move(e1);

// Leaves e1 in an 'invalidated' state (implementation defined). Accessing e1 is UB.

- Explicitly

releaseownership. This stops the unique pointer instance from actively managing the raw memory and returns the raw pointer.

T *raw_ptr = e1.release(); // Frees the memory

Terminate the object and replace the ownership

e1.reset(new Entity("efgh")); // replace the ownership

Custom Destructors!

A cool thing about smart pointers is that they accept custom destructors. For example:

Entity *e = new Entity;

std::unique_ptr<Entity, std::function<void(Entity*)>> uptr(e, [&](Entity *e){

std::cout << "Custom destructor!" << std::endl;

});

// Output: Constructor!\nCustom destructor!\n

A revised implementation of std::unique_ptr

// A slightly superior implementation.

template<typename T>

class unique_ptr{

public:

explicit unique_ptr() noexcept : obj(nullptr) {}

explicit unique_ptr(T* obj) noexcept : obj(obj) {}

explicit unique_ptr(unique_ptr &other) = delete;

unique_ptr& operator=(const unique_ptr&) = delete;

unique_ptr(unique_ptr&& other) noexcept : obj(other.release()) {}

unique_ptr& operator=(unique_ptr&& other){

if(this != &other)

reset(other.release());

return *this;

}

~unique_ptr() noexcept { delete obj; }

T* get() { return obj; }

T* release() {

T* cpy = obj;

obj = nullptr;

return cpy;

}

void reset(T *upd) noexcept {

delete obj;

obj = upd;

}

private:

T* obj;

};

std::shared_ptr

Like previously mentioned, a std::shared_ptr is an unique pointer that allows ‘sharing’ ownership. This means that shared pointers can be copied and assigned.

std::shared_ptr<Entity> outer;

{

std::cout << "Start of inner scope" << std::endl;

std::shared_ptr<Entity> inner = std::make_shared<Entity>("abcd");

std::cout << "End of inner scope" << std::endl;

}

/**

* Output:

* Start of inner scope

* P-Constructor!, name: abcd

* End of inner scope

* Destructor!

*/

You will notice, that we were now able to use the copy-assignment operator with our shared pointer object. And further, even though the inner shared pointer is out of scope, the destructor is called only after the outer shared pointer (which received ownership via the copy-assignment operator) goes out of scope.

## `std::make_shared`

Apart from the same reasons listed for std::make_unique, there are more reasons to use std::make_shared instead of std::shared_ptr<Entity> inner(new Entity()). The reason somewhat comes down to the implementation and overhead associated with shared pointers.

### Implementation Notes

How std::shared_ptr is implemented is ultimately up to the compiler and what standard library we are using. It is implementation specific, and there is no standard defined for how the sharing must be implemented. However, it is almost always implemented in the popular libraries using reference counting.

What this means is that a shared pointer essentially manages two blocks of memory. There is a “control block” which contains information regarding to the reference count and then there’s the memory that’s being managed. In essence, you can think of the control block as being a dynamically allocated integer object that keeps reference count of the number of shared pointers which hold ownership over the managed memory that are still in scope.

This memory only needs to be allocated once, in the normal constructor of a shared pointer. Because this is when we are stating the existence of a new ownership. Now when ownership is being copied, we just need to increment this reference count. This can be done in the copy constructor and copy-assignment operator calls. Finally, as each shared pointer goes out of scope and it’s destructor is called, it can just decrement the value of the reference count. When the final shared pointer goes out of scope, decrementing the reference count to zero, we now that there exist no more shared pointers which ownership of the memory being managed, and hence we can then safely de-allocate both blocks of memory.

Why does this matter? Unlike with std::unique_ptr, there is an overhead associated with using a std::shared_ptr in the form of the control block memory that it must additionally allocate and share. If we call std::shared_ptr<Entity> inner(new Entity()), there is first an allocation in the inner call to the new operator. This is then followed by an extra call to allocate the control block memory. That’s 2 allocations.

However, with std::make_shared, it can actually construct them together, essentially halving the allocation requests and also keeping them close by in memory. This is significantly faster. (Remember, memory allocation cost is often very expensive in comparison to the other book-keeping operations here). Hence it’s almost always a good idea to use std::make_shared instead of passing an already allocated memory-pointer to std::shared_ptr.

std::weak_ptr

std::weak_ptr is the final member of our little group of smart pointers which completes C++’s ownership ideology. A std::weak_ptr can copy ownership from a std::shared_ptr, except this ownership is weak. You can imagine it as a shared pointer which when copying, does not increase the reference count of the original shared pointer. Due to this, it is possible the weak pointer is still in scope but because all the strong owners of the managed memory have gone out of scope, the memory has been freed and the weak pointer is now in an invalidated state.

It’s like saying, I don’t actually want ownership of the object, but I just want to keep a reference to the allocated entity. This means std::weak_ptr has member functions that allow querying things like “is the memory that the weak pointer is pointing to still alive?”

std::weak_ptr<Entity> outer;

std::cout << "Outer weak_ptr use count: " << outer.use_count() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Outer weak_ptr expired: " << outer.expired() << std::endl;

{

std::cout << "Start of inner scope" << std::endl;

std::shared_ptr<Entity> inner = std::make_shared<Entity>("abcd");

std::cout << "Inner shared_ptr use count: " << inner.use_count() << std::endl;

outer = inner;

std::cout << "Outer weak_ptr use count: " << outer.use_count() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Outer weak_ptr expired: " << outer.expired() << std::endl;

std::cout << "End of inner scope" << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "Outer weak_ptr use count: " << outer.use_count() << std::endl;

std::cout << "Outer weak_ptr expired: " << outer.expired() << std::endl;

/**

* Output:

* Outer weak_ptr use count: 0

* Outer weak_ptr expired: 1

* Start of inner scope

* P-Constructor!, name: abcd

* Inner shared_ptr use count: 1

* Outer weak_ptr use count: 1

* Outer weak_ptr expired: 0

* End of inner scope

* Destructor!

* Outer weak_ptr use count: 0

* Outer weak_ptr expired: 1

*/

The above code block shows the working of the two pointers succinctly. The weak pointer does not increase the use_count of the shared pointer. And as soon as the shared pointer exits the inner scope, the memory is freed and our shared pointer now points to invalidated memory, as shown in the output of outer.expired().