"What Goes Around Comes Around" - The History of Database Systems - Part 1 (1960 - 2000)

Interactive Graph

Table of Contents

Abstract

This will be my first blog post / set of notes taken for a paper I’ve read. The paper titled, What Goes Around Comes Around was written by Michael Stonebraker (Turing Award Winner and the man behind the POSTGRES (and INGRES) database(s)) and Joseph Hellerstein (Has a casual h-index of 105). Usually, the abstract of the paper provides an excellent summary, and this one is no exception.

Abstract This paper provides a summary of 35 years of data model proposals, grouped into 9 different eras. We discuss the proposals of each era, and show that there are only a few basic data modeling ideas, and most have been around a long time. Later proposals inevitably bear a strong resemblance to certain earlier proposals. Hence, it is a worthwhile exercise to study previous proposals.

In addition, we present the lessons learned from the exploration of the proposals in each era. Most current researchers were not around for many of the previous eras, and have limited (if any) understanding of what was previously learned. There is an old adage that he who does not understand history is condemned to repeat it. By presenting “ancient history”, we hope to allow future researchers to avoid replaying history.

Unfortunately, the main proposal in the current XML era bears a striking resemblance to the CODASYL proposal from the early 1970’s, which failed because of its complexity. Hence, the current era is replaying history, and “what goes around comes around”. Hopefully the next era will be smarter.

This paper primarily analyzes the evolution of various data models and their rise to popularity or extinction, contingent on their features and commercial decisions by big market players. I will also sprinkle in a bit of history about the evolution of databases that I learnt from 01 - History of Databases (CMU Advanced Databases / Spring 2023 and Postgres pioneer Michael Stonebraker promises to upend the database once more - The Register as well.

Useful Concepts

Below we’ll define a few concepts that’ll be useful to know about when reading about the evolution of database systems.

Physical Data Independence

We can define physical data indepence as the ability to change the core algorithms and / or access patterns related to how data is accessed and stored at the physical (disk) level without affecting the logical layer (application level code) written on top of it.

In short, changing the DBMS’s underlying core data structure from a B+ Tree to a Hashtable should not require rewriting any part(s) of the applications written on top of this DBMS. The APIs provided by the DBMS must ensure this independence.

This allows the DBMS software to optimize it’s performance by altering storage formats, use new hardware features, etc. while also providing guarantees to application developers for a stable & consistent interface to the DBMS.

Logical Data Independence

This is harder to define clearly, but in short, changes to the logical table definition (such as schema, relations, attributes, etc.) should not require rewrite of application level code. For example, if I recently started logging information about whether or not a patient had been vaccinated for COVID-19 in a Hospital’s DBMS, I would not want the application software that did not need this extra attribute to break.

The Supplier / Parts Table

This isn’t a concept, but we’ll be using the standard supplier-parts table or the employer-employee table for giving examples in the future, so it’s useful to know the structure beforehand.

Let’s suppose you’re NASA, and you need a bunch of parts for your new Space Mission. There are also a set of suppliers who provide some subset of these parts, in various batch order sizes for varying prices. You want to build a system that allows you to query this data to figure out useful information such as:

- Which supplier(s) supply part $x$?

- Which part(s) are supplied by supplier $x$?

- What all parts of type $y$ are supplied by supplier $x$?

- etc.

The (Real) Eras Tour

Stonebraker and Hellerstein roughly summarize the period from 1960s to the 2000s into 10 distinct (but not disjoint) eras. Each era has it’s own intriguing idea and starts a debate of old model vs new model between people in the opposing camps. Ultimately ease of use and commercial requirement + adoption is the primary driver of success for these models.

Over the years, SQL and the relational model have come out as the juggernaut in the space. Every decade, someone invents a challenger or replacement to SQL, which then proceeds to fail and/or have it’s key ideas absorbed into the standard. Some of these will be discussed in What Goes Around Comes Around… and Around… - The History of Database Systems - Part 2 - (2000 - 2020).

It is also useful to know that many of the older models mentioned below (even IMS) are still in use today, but almost every instance of such a database is used in legacy code. ATMs for example still use IMS because they don’t have a reason to migrate their legacy code, however no startup starting off today would ever choose to use IMS.

IMS Era (Late 1960s - 1970s)

Integrated Data Store (IDS)

Before we get to IMS, there was IDS. This is perhaps the earliest known instance of a “DBMS” product. It was designed by the computer division of General Electric by Charles William Bachman, who received the ACM Turing Award in 1973 for his work on DBMS.

Motivation

In the 1950s, there was a huge rush for buying computers and using them to automate work. However, getting computers to do useful tasks turned out to be a lot harder than expected. Companies mostly used them in narrow clerical tasks and needed more from computers to justify their cost.

Various firms tried to build such “totally integrated management information systems”, but the hardware and software of the era made that difficult. Each business process ran separately, with its own data files stored on magnetic tape. A small change to one program might mean rewriting related programs across the company. But business needs change constantly, so integration never got very far.

The Birth of IDS

When working at GE, partially thanks to the invention of the disk drive, his department managed to successfully build a management system called the Manufacturing Information and Control System (MIACS). This then grew to become IDS. IDS provided application programmers with a powerful API to manipulate data, an early expression of what would soon be called a Data Manipulation Language (DML).

IDS managed “records” on disk and provided programmers with an abstraction over the physical data layer. This provided programmers with physical data independence, they need not rewrite all their application logic if a minor change was made to how the disk accesses were made. He managed to squeeze MIACS and IDS into just 40Kb of memory.

Honeywell

GE built this technology for a timber company in Seattle, and then later ended up spinning out the custom solution as a standalone software product. GE was around the third best computer seller in the market, which wasn’t good enough for them. So they sold their computing division to Honeywell, who continued to sell the product for a while.

Characteristics of IDS

- Tuple-at-a-time queries: This essentially means that when we define operations or queries, IDS would use

forloops to iterate one tuple at a time and do computations. - Network Data Model: More on this and Bachman when we talk about CODASYL.

Information Management System (IMS)

IMS was a DBMS product released by IBM around 1968. It was one of the earlies DBMS systems to introduce the notion of a record type, that is, a collection of named fields with their associated data types. It also introduced the notion of enforcing constraints. Every record instance had to satisfy the record type description. In simpler terms, it was perhaps the first DBMS to introduce the idea of schema.

Hierarchical Data Model

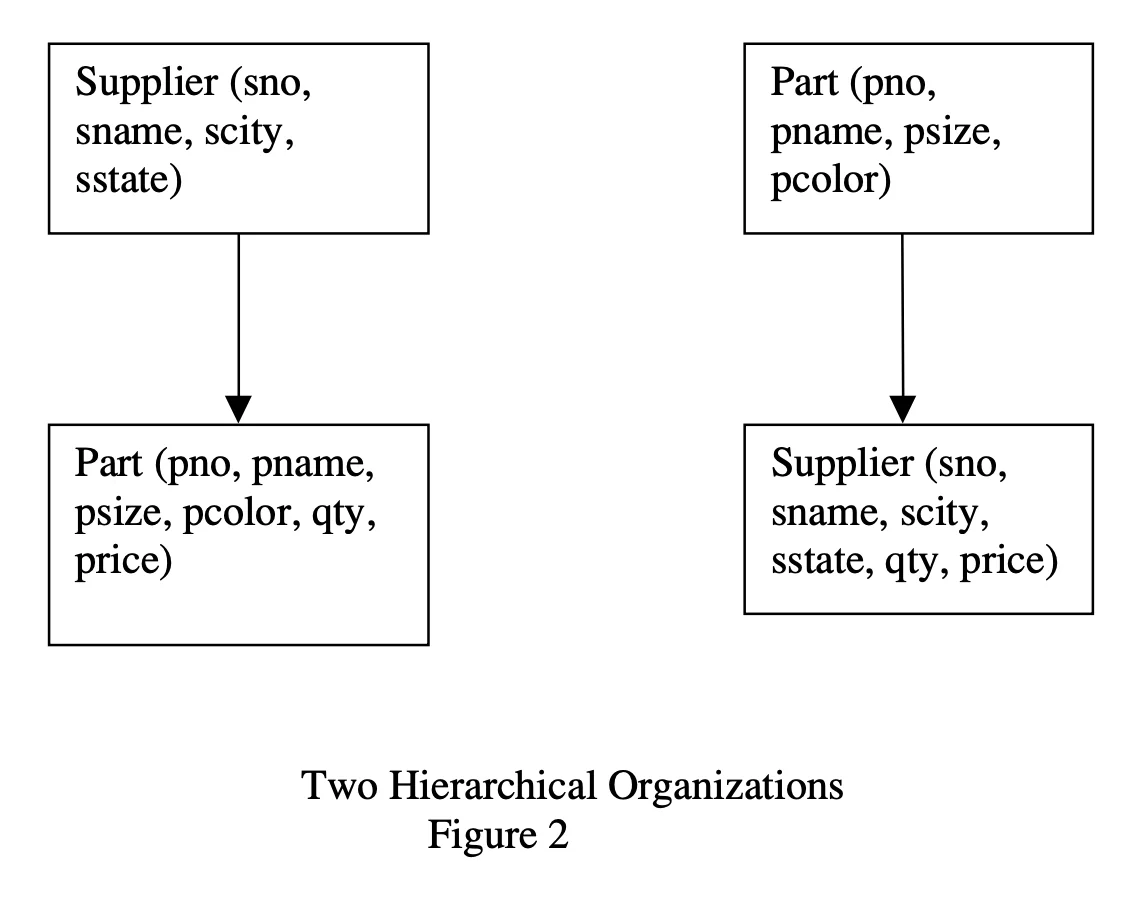

IMS was also the first DBMS to use a hierarchical data model. Every record type, except the root had a single parent record type. In other words, you had to define the record types such that they formed a directed tree. This is how we’d have to represent our supplier-parts table using this mode:

Either Supplier as the parent to Part or vice-versa. While it was an interesting take, it had some fundamental issues:

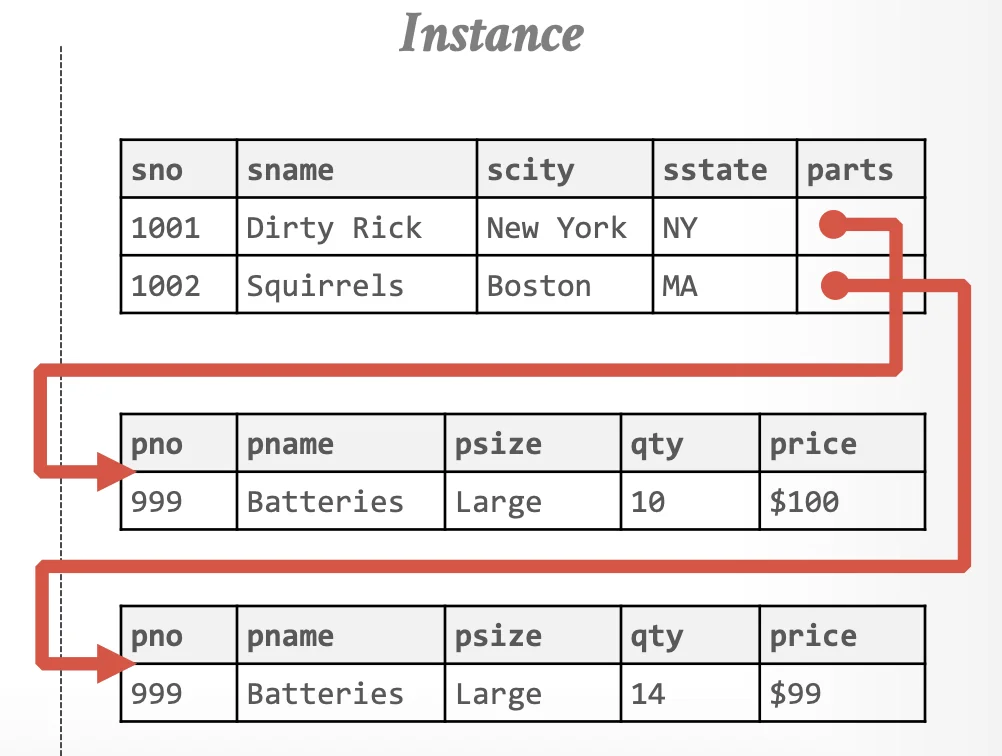

- Difficult to Eliminate Redundant Information: In the first schema, for every supplier who supplies a part, we’d have to repeat part information. Essentially, let’s say we had 2 vendors selling the same product for different prices, we’d need to have multiple records of the same

pname. Now if we wanted to change the name of the part, we’d need to update every duplicatedpnamefield. This can lead to inconsistency issues when updated may fail midway etc.

- Corner Case Issues: In a strict hierarchy, we cannot have a supplier who does not supply anything and vice versa since the

partsrecord is a part of aSupplierrecord. - Record-at-a-time: IMS ordered records by a hierarchical sequence key (HSK). In short, it’s basically records ordered in DFS order of the record-type tree. You could use it’s DML language (DL/1) to fetch the next record or fetch the next record within parent. You could do interesting tree / sub-tree type traversals but it was still record-at-a-time. Optimization of queries was completely left to the programmer.

- Lack of Physical Data Independence: IMS supported multiple physical data storage formats.

- Sequential storage

- Indexed B-Tree

- Hash table However, if you switched between formats because you needed support for range queries or for faster lookups, the API exposed to the application programmer was also different.

- Limited Logical Independence: Because DL/1 was not defined on the physical data layer, IMS supported limited logical independence. If we modified record types, they’d essentially be some subtrees in the logical database record tree. A DL/1 program can just use the logical database definition it was originally written for by allowing the logical database to exclude the subtrees that contain redefined record types.

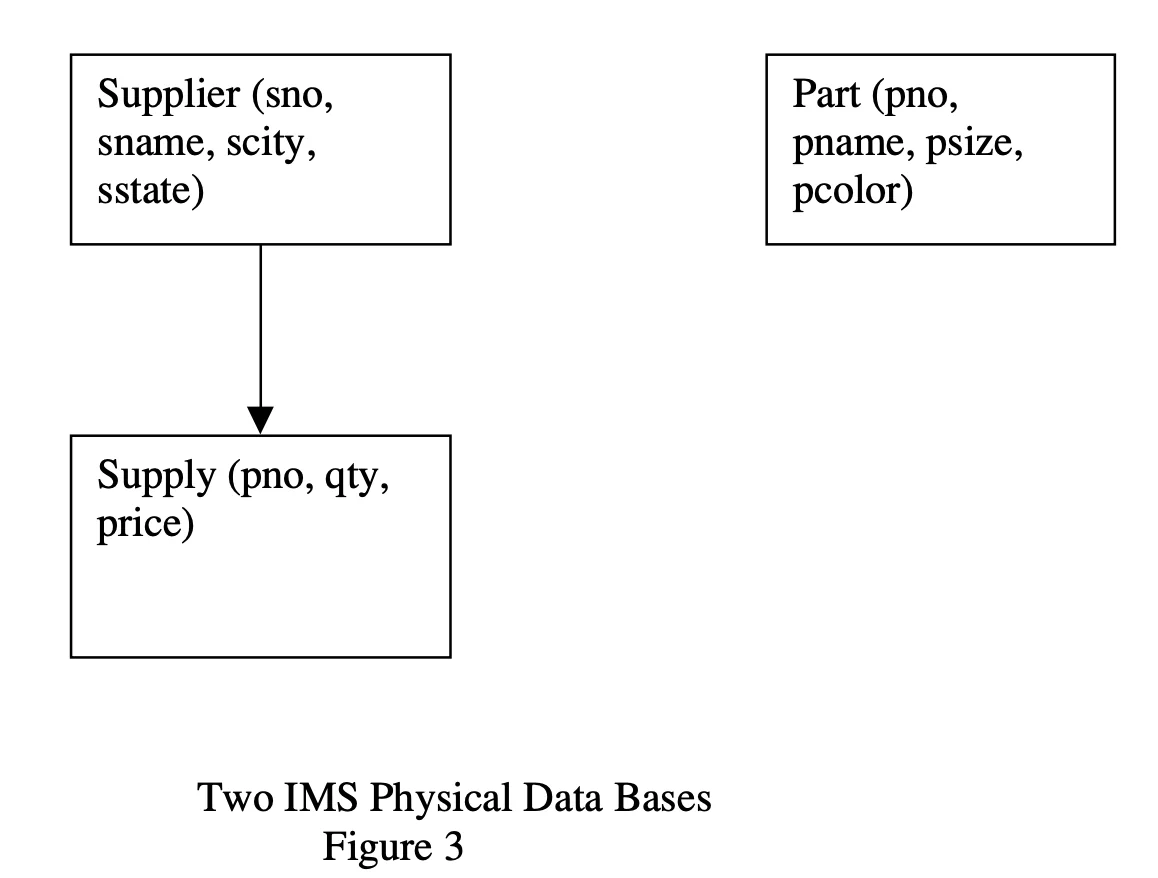

- Response to fix data redundancy failed: The response to fixing the redundancy issue was to allow for the following:

Physical storage:Logical storage:

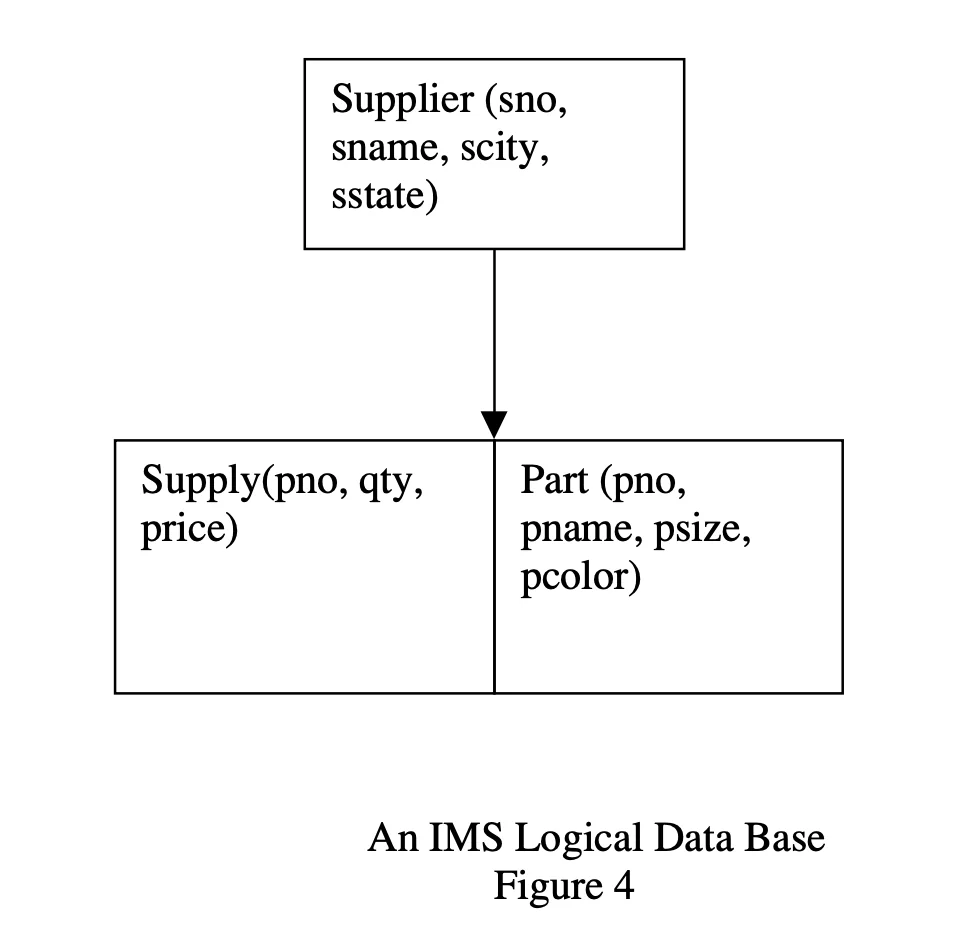

It allowed to “graft” two tree-structured physical databases into a logical data base (with many restrictions). Essentially, since

It allowed to “graft” two tree-structured physical databases into a logical data base (with many restrictions). Essentially, since

PartandSupplyare two separate physical tables themselves, there is no repeated information. However, computing the logical grafted block likely would involve joining the two tables for queries on theSupplierlogical database. This introduced a lot of undesirable computational and design complexity.

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 1: Physical and logical data independence are highly desirable

- Lesson 2: Tree structured data models are very restrictive

- Lesson 3: It is a challenge to provide sophisticated logical reorganizations of tree structured data

- Lesson 4: A record-at-a-time user interface forces the programmer to do manual query optimization, and this is often hard.

CODASYL Era (1970s)

Remember Charles Bachman? The man behind IDS? He didn’t stop there. COBOL programmers proposed a standard for how programs will access a database. They were essentially trying to build a standard for DBMS and Bachman lead the work on CODASYL.

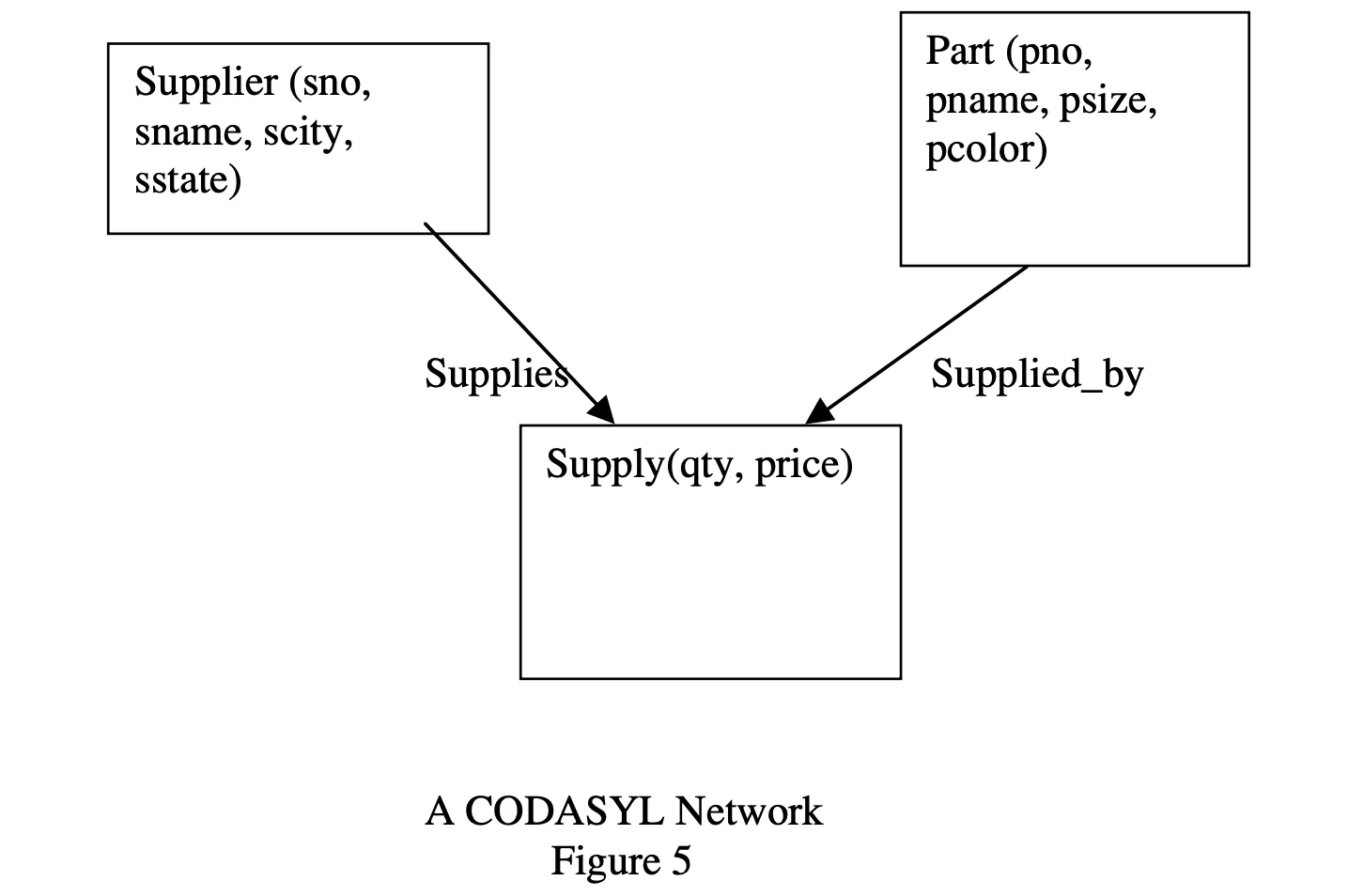

The natural next thought from IMS was to move from a tree like structure to a general graph network structure. Here’s how we’d represent the Supplier-Parts table in CODASYL.

Notice that in this DAG, the directed edges have names. In CODASYL, these directed edges represent sets. It indicates that for each record instance of the owner record type (the tail of the arrow) there is a relationship with zero or more record instances of the child record type (the head of the arrow). It represents 1-n relationships between owner and children.

This solved some of the issues from the hierarchical model, for example, we can have suppliers who don’t supply any parts (empty set). However, the fact that you had to maintain sets of “relation” info also implied that there existed lots of different ways to implement certain things. There was no logical or physical independence. It is also a record-at-a-time language.

Consider this example of pseudo for a program that is tasked with finding all “red” parts supplied by supplier $x$.

Find Supplier (SNO = x)

Until no-more {

Find next Supply record in Supplies

Find owner Part record in Supplied_by

Get current record -check for red—

}

For each record, you had to possibly traverse multiple sets of information to obtain what you actually wanted. Several implementations of sets were proposed that entailed various combinations of pointers between the parent records and child records.

CODASYL solved many of the issues that IMS faced with it’s graph model that allowed for more expressive relations. However, it still lacked physical and logical independence and the added complexity was simply too much, both for the developer implementing the database internals and for the developer programming an application layer on top of CODASYL.

In IMS a programmer navigates in a hierarchical space, while a CODASYL programmer navigates in a multi-dimensional hyperspace. In IMS the programmer must only worry about his current position in the data base, and the position of a single ancestor (if he is doing a “get next within parent”). In contrast, a CODASYL programmer must keep track of the: - The last record touched by the application - The last record of each record type touched - The last record of each set type touched

In his 1973 Turing Award lecture, Charlie Bachmann called this “navigating in hyperspace”

In addition, a CODASYL load program tended to be complex because large numbers of records had to be assembled into sets, and this usually entailed many disk seeks. As such, it was usually important to think carefully about the load algorithm to optimize performance. Hence, there was no general purpose CODASYL load utility, and each installation had to write its own

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 5: Networks are more flexible than hierarchies but more complex

- Lesson 6: Loading and recovering networks is more complex than hierarchies

Relational Era (1970s and Early 1980s)

Roughly around the same time, Edgar F. (“Ted”) Codd was working on his relational model. Codd was originally a mathematician who was motivated by the fact that IMS programmers spent a lot of their time working on maintenance due to IMS neither supporting logical nor physical data independence.

It should be noted, incidentally, that the relational model was in fact the very first abstract database model to be defined. Thus, Codd not only invented the relational model in particular, he actually invented the data model concept in general.

His proposal was threefold:

- Store the data in simple data structures (tables) It was difficult for previous databases to provide logical independence due to their use of complex data structures such as B-trees, hierarchical models, etc.

- Access it through a high level set-at-a-time DML Using a high enough level language, it was possible to provide a high degree of physical data independence where you don’t need to specify a fixed storage proposal. Think the modern day SQL queries you are used to vs the “getNext” and similar methods programmers had to use back in the day. Also, set-at-a-time would allow for programmers to reduce number of lines of code per query significantly while also opening the door to a slew of database query optimizations.

- There was no necessity for a physical storage proposal For a database that supports complete logical and physical data independence, it was not necessary to specify a physical storage format. DBMS users should be able to specify the data structure that best suits their queries and this should be hot-swappable with no rewrite at the application layer.

Ted Codd was also interested in the possibility of extending his relational ideas to support complex data analysis, coining the term OLAP (On-Line Analytical Processing) as a convenient label for such activities. At the time of his death, he was investigating the possibility of applying his ideas to the problem of general business automation.

Moreover, the relational model has the added advantage that it is flexible enough to represent almost anything. It fixed all the issues IMS had in representing complex relationships using the hierarchical model while also providing logical and physical data independence, something CODASYL could not. This immediately sparked off a huge debate between CODASYL supporters and Relational Model supporters.

Issues with CODASYL

- CODASYL was extremely complex to work with. For software developers working at both the database code and application code.

- No logical or physical data independence meant a lot of time and money was spent on labour rewriting codebases.

- Record-at-a-time programming was too difficult to optimize and had to be done by each application that interacted with a DBMS. I find this extremely similar to the “compiler cannot optimize as good as a human” debate from the programming languages world.

- CODASYL was not flexible enough to represent certain relationships.

Issues with the Relational Model

- It was complicated, extremely rigorous, formal and difficult to understand for your average programmer (Ted Codd was a mathematician).

- It is extremely difficult to implement the relational model efficiently due it’s lack of advanced data structure usage. (This would mostly be solved later due to advanced in the field of Query Optimization. Pretty much “compilers” that beat all but the world’s best at query plan generation.)

A debate between the two and their supporters, held at an ACM workshop (SIGMOD) in 1974, is remembered among database researchers as a milestone in the development of their field. Bachman stood for engineering pragmatism and proven high performance technology, while Codd personified scientific rigor and elegant but unproven theory. Their debate was inconclusive, which was perhaps inevitable given that no practical relational systems had yet been produced. Charles William Bachman - ACM Page

Over a period of time, once System R and INGRES had proved that efficient implementations of the Relational Model was possible, the relational advocates also agreed that Codd’s mathematical language was too complicated and changed their proposed language to SQL or QUEL. Meanwhile, on the CODASYL side, LSL was a language which allowed set-at-a-time querying for networked databases, offering physical data independence. They also showed that it was possible to clean up the complexities of the network data model somewhat. (TODO, don’t know how.)

This debate eventually lead to the commercial war for CODASYL vs Relational Systems, which would decide which specification lived and which would die.

The Commercial War for CODASYL vs Relational Model

VAX (minicomputers implementing the idea of a virtual memory space) were a market dominated by relational databases. VM made implementing relational ideas easier. They were also very fast. Further, CODASYL was written in assembler which made migration to VAX hard. In contrast, the mainframe market was still dominated by IMS and other non-relational database systems.

However, this changed abruptly in 1984. IBM who controlled most of the market share was the leader in this space. They introduced DB/2 which was a relational DB which was comparatively easier to use and was the “new tech.” This signaled that IBM was serious about RDBMS and backing it, which eventually made it win the war. They effectively declared that SQL was the de-facto query language.

Interestingly, there was a standards committee setup to decide the standard language that would be used to query RDBMS. At this time, the two main competitors were QUEL and SQL. QUEL, backed by Stonebraker had a lot of nicer semantics compared to SQL For example, you could use

fromright after theselectinstead of at the end of your query.) However, Stonebraker refused to attend the conference due to his dislike of standards committees and such (average academician :p) which lead to SQL becoming the standard. - Andy Pavlov in some CMU lecture

Interesting fact number 2, IBM tried to build a relational frontend transpiler sort of interface on top of IMS (To provide a more elegant migration to RDBMS). But the complexity & logical dependence of DL/1 made it very difficult to implement. IBM had to abandon and do a dual-db strategy, which also consequently made them declare a clear winner for the debate.

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 7: Set-a-time languages are good, regardless of the data model, since they offer much improved physical data independence.

- Lesson 8: Logical data independence is easier with a simple data model than with a complex one.

- Lesson 9: Technical debates are usually settled by the elephants of the marketplace, and often for reasons that have little to do with the technology.

- Lesson 10: Query optimizers can beat all but the best record-at-a-time DBMS application programmers.

Entity-Relationship Era (1970s)

Peter Chen came up with the Entity-Relationship model as an alternative to all the other models in the 1970s. The model he proposed can be described as follows:

The Model

- Entities: Loosely speaking, objects that have an ’existence’, independent of any other entities in the database. Examples:

Supplier,Part. - Attributes: Data elements that describe entities. For

Part, attributes would includepno,pname,psize,pcolor, etc. - Keys: Unique attributes designated to together identify entities uniquely.

- Relationships: Connections between entities. Example:

SupplyconnectsPartandSupplier. Similar to the CODASYL model. They can be of multiple types:- Types:

- 1-to-1: One entity relates to one other.

- 1-to-n: One entity relates to multiple others.

- n-to-1: Multiple entities relate to one.

- m-to-n: Multiple entities relate to multiple others (e.g.,

Supplyis m-to-n because suppliers can supply multiple parts, and parts can be supplied by multiple suppliers).

- Types:

- Relationship Attributes: Properties describing the relationship. Example:

qtyandpricein theSupplyrelationship.

Failure In Acceptance as DBMS Data Model

The model did not gain acceptance as a DBMS data model for several reasons, as speculated by the authors: it lacked an accompanying query language, it was overshadowed by the more popular relational model, and it resembled an updated version of the CODASYL model, which may have contributed to its lack of distinction.

Success In Database Schema Design

The ER model ended up being a model that helped solve the issue of finding “initial tables” for applying normalization on in the relation only tables model. Database Administrators (DBAs) used to struggle with coming up with good database schema design. The Entity-Relationship model, with it’s notion of “Entities”, made it a lot simpler for DBAs to model initial tables on paper quickly and get schemas for tables to use in the relational model. It was easy to convert E-R models to the 3rd Normal Form. (Normalization Theory in DBMS)

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 11: Functional dependencies are too difficult for mere mortals to understand. Another reason for KISS (Keep it simple stupid).

R++ Era (1980s)

The authors use the term “R++” to talk about an era where most of the research involved showing example programs which performed poorly or were difficult to implement on a RDBMS and added features to the Relational Model to improve / fix it.

Lot of application specific additions were proposed to the relational model. These were some of the identified most useful constructs:

- set-valued attributes: In a

Partstable, it is often the case that there is an attribute, such asavailable_colors, which can take on a set of values. It would be nice to add a data type to the relational model to deal with sets of values. - aggregation (tuple-reference as a data type): In the RM model for the Supply relation, we had two foreign keys

snoandpnowhich point to tables in other tables. Instead of this, we can just have pointers to these tuples. This “cascaded dot” notation allowed one to query the Supply table and then effectively reference tuples in other tables. It allowed one to traverse between tables without having to specify an explicit join. - inheritance: Gem implemented a variation of inheritance you find in OOP languages in the DBMS context. Inherited types inherited all the attributes of their parent. However, the problem with this was that while it allowed easier query formulation that in a conventional relational model, there was very little performance improvement. Especially since you could simulate this in a RM model by substituting a tuple for a data type.

Most commercial vendors were focusing on improving transaction performance and scalability. Since R++ ideas offered little improvement and not much revenue potential there was little technology transfer of R++ ideas from academia into the commercial world.

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 12: Unless there is a big performance or functionality advantage, new constructs will go nowhere.

Semantic Data Model Era (Late 1970s and 1980s)

This was pretty much an effort at quite literally bringing Object Oriented Programming (OOP) ideas to the DBMS world (please no!). They suggested that the relational model was “semantically impoverished” and wanted to allow for expressing classes and such. These efforts were usually called “Semantic Data Models.”

They expanded on aggregation, inheritance and set-valued attributes from the R++ era and allowed classes to extend aggregation to refer to an entire set of instances of records in some other class. Also allowed inverse of these attributes to be defined. They also wanted generalized inheritance graphs, extending on the idea of inheritance in SDM. This was basically just multiple inheritance. Lastly, classes can have class variables, for example the Ships class can have a class variable which is the number of members of the class.

However… These models were extremely complex and did not offer any significant value over RDBMS. SQL had also gained popularity as the intergalactic standard for database querying which made it very difficult to displace it’s position in the market. Similar to R++ proposals, there was not enough reward-to-cost ratio to justify them. And in the case of SDMs, they were also far too complex. Throwback to the CODASYL / IMS era :)

Lessons From the Paper

- None :(

- On a more serious note, the exact same lesson that was gained from the R++ era.

Object-Oriented Era (Late 1980s and Early 1990s)

During this period there was a new wave of interest into “Object Oriented DBMSs” (god no why?!). Advocated pointed to an “impedance mismatch” between RDBMS and OO languages like C++. Since RDBMS systems had their own data systems, naming, and return types, we needed some conversion layers to make code transpile between the two interfaces. They claimed that it would be nicer if DBMS operations were done via language built in constructs and we had persistent variables that could point to either locations in memory or disk (to aid with implementing / interfacing with DBMS operations).

While a ‘persistent programming language’ would allow for much cleaner constructs than a SQL embedding, each programming language would have to be extended with DBMS-oriented functionality. However,

Unfortunately, programming language experts have consistently refused to focus on I/O in general and DBMS functionality in particular. Hence, all programming languages that we are aware of have no built-in functionality in this area. Not only does this make embedding data sublanguages tedious, but also the result is usually difficult to program and error prone. Lastly, language expertise does not get applied to important special purpose data-oriented languages, such as report writers and so-called fourth generation languages.

In the 1980s there was another surge in implementing a persistent C++ version with it’s own runtime (PLEASE WHY?!). These vendors mainly focused on targeting niches and engineering CAD applications. However, they did not see much commercial success. The authors of the paper list a few possible reasons:

- Absence of leverage: The OODB vendors presented the customer with the opportunity to avoid writing a load program and an unload program. This is not a major service, and customers were not willing to pay big money for this feature. 2. No standards: All of the OODB vendor offerings were incompatible. 3. Relink the world: In anything changed, for example a C++ method that operated on persistent data, then all programs which used this method had to be relinked. This was a noticeable management problem. 4. No programming language Esperanto: If your enterprise had a single application not written in C++ that needed to access persistent data, then you could not use one of the OODB products.

There was an outlier company called O2 which had a high level declarative language called OQL embedded into a programming language and also focused on business data processing.

There is a saying that “as goes the United States goes the rest of the world”. This means that new products must make it in North America, and that the rest of the world watches the US for market acceptance.

Unfortunately for O2, they were a French company and entered the US market too late.

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 13: Packages will not sell to users unless they are in “major pain”

- Lesson 14: Persistent languages will go nowhere without the support of the programming language community.

Object-Relational Era (Late 1980s and Early 1990s)

Motivation

This model was motivated by INGRES’s inability to efficiently solve problems related to 2 dimensional search. B+ trees allowed efficient search on one dimension or on one index. But when the search query involves finding rectangle intersection or points inside a rectangle such queries cannot be solved efficiently by traditional B+ tree implementations of DBMS.

Idea

The pioneering idea here is to generalize relational systems to allow for user defined types (UDTs), user defined functions (UDFs), user defined operators and user defined access methods. This allows more sophisticated users to solve the 2d search problem using data structures optimized for these types of queries, such as Quad trees or R-trees.

In essence, we want to replace the hard coded B+ tree logic with a framework that handles general case well and allows sophisticated users to go beyond and define custom user defined protocols. Postgres UDT and UDFs generalized this notion to allow code to be written in a conventional programming language and to be called in the middle of processing conventional SQL queries.

Compared to previous R++ and SDM eras, instead of providing built-in support for aggregation and generalization, Postgres UDT and UDFs provide a better framework for allowing users to optimize for their own types and queries.

UDFs

There is another notion of UDFs in use today. Many DBMS systems call stored procedures UDFs. Instead of making transactions use one round trip message between DBMS and client per statement, they allowed the client to store “defined procedures” on the DBMS which can be called via a single message, to eliminate context switch time. These UDFs are “brain dead” in the sense it can only be executed with constants for its parameters. They also required DBMS software to handle errors on the DBMS side since some procedures might have runtime errors which need to be handled well.

Postgres

In addition, Postgres also implemented less sophisticated notions of inheritance, and type constructors for pointers (references), sets, and arrays. This latter set of features allowed Postgres to become “object-oriented” at the height of the OO craze. Postgres was commercialized by Illustra and then acquired by Informix. This gave Postgres access to a fast OLTP engine. Also gave them increased market share to convince more business to adopt Postgress’ UDF / UDTs. Worked well for the GIS market and large content repositories (Used by CNN & BBC).

Conclusion

- This new model blurs the distinction between data and code by allowing you to put code in the database and user-defined access methods.

- However widespread adoption was significantly hindered by lack of standards, which seems to be a huge requirement to gain significant adoption by the big tech players in the market.

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 14: The major benefits of OR is two-fold: putting code in the data base (and thereby blurring the distinction between code and data) and user-defined access methods.

- Lesson 15: Widespread adoption of new technology requires either standards and/or an elephant pushing hard.

Semi-Structured Era (Late 1990s and 2000s)

In 2004, we saw a push toward databases for semi structured data which exemplified two characteristics that we had already seen do poorly in the past:

Schema Last

The data instances that need to be stored must be self describing. Without a self-describing format, a record is merely “a bucker of bits”. To make a record self-describing, one must tag each attribute with metadata that defined the meaning of the attribute. However, by not requiring a schema in advance, we lose a lot of integral properties we see in today’s database systems like constraint checking, validity, etc. Consider the records of the following two people:

Person:

Name: Joe Jones

Wages: 14.75

Employer: My_accounting

Hobbies: skiing, bicycling

Works for: ref (Fred Smith)

Favorite joke: Why did the chicken cross the road? To get to the other side

Office number: 247

Major skill: accountant

End Person

Person:

Name: Smith, Vanessa

Wages: 2000

Favorite coffee: Arabian

Passtimes: sewing, swimming

Works_for: Between jobs

Favorite restaurant: Panera

Number of children: 3

End Person:

In this example, we can see records which may only appear in one of the two, which may appear under a different name (alias) in the other record or which may appear in varying formats or meanings under the same name. This is an example of semantic heterogeneity. Such examples are extremely difficult to carry out query processing on, since there is no structure on which to base indexing decisions and query execution strategies. However, there are very few instances where we encounter such semantically heterogenous data in business practices.

For applications that deal with rigidly structured data or rigidly structured data with some text fields, a standard RDBMS system is more than capable of handling all business needs. For applications dealing with only text, the schema last framework does not work since schema last requires there to be some self-tagged metadata or “semi-structure” in the data it stores, which free text does not have. The problem of dealing with free text data is tackled by people working on Information Retrieval systems.

It is very difficult to come up with applications which might have to deal with “semi-structured” data. The authors cite advertisements and resumes as examples, but even in this field we have seen companies require mandated fields for resume entry which leads to more structured data parsing. In essence, it is better to avoid designing a system that requires “semi-structured” data than use a schema last system.

XML Data Model

Document Type Definition (DTDs) and XML Schema (XML) were intended to deal with the structure of formatted documents. They are both essentially document markup languages. DTDs & XML can, for example, be used to define the schema used by a DBMS table. However, there were attempts to use these models for actual DBMS applications. However, these were categorized by the authors of the paper as being seriously flawed (And I would agree, since I’m reading this 20 years after the date this paper was published :) The primary concerns cited are the sheer amount of complexity such a model introduces. We have already seen every DBMS model not following KISS (Keep It Simple Stupid) fail miserably. XML decides to then define a model where:

- Records can be hierarchical (Like in IMS)

- Records can have “links” or references to other records (Like in CODASYL & other network models)

- Records can have set-based attributed (Like in SDM)

- Records can inherit from other records in several ways (Like in SDM & OO)

On top of all this, XML also touted support for other features. One notable feature being union types. This is in the exact context as used by it’s C counterpart. An attribute can be one of multiple types. For example, the “works for” field in an employee’s record could be a department number of the name of an outside firm. (Yes you can also just give outside firms unique IDs but for the sake of the example…) However, B-tree indexes for records containing union attributes required one index per record in the type. And if you did joins between union types containing $N$ and $M$ base types, you’d need $max(N, M)$ plans to co-ordinate.

This is how the paper places it’s predictions.

Obviously, XMLSchema is far and away the most complex data model ever proposed. It is clearly at the other extreme from the relational model on the “keep it simple stupid” (KISS) scale. It is hard to imaging something this complex being used as a model for structured data. We can see three scenarios off into the future.

Scenario 1: XMLSchema will fail because of excessive complexity.

Scenario 2: A “data-oriented” subset of XMLSchema will be proposed that is vastly simpler.

Scenario 3: XMLSchema will become popular. Within a decade all of the problems with IMS and CODASYL that motivated Codd to invent the relational model will resurface. At that time some enterprising researcher, call him $Y$, will “dust off” Codd’s original paper, and there will be a replay of the “Great Debate”. Presumably it will end the same way as the last one. Moreover, Codd won the Turing award in 1981 for his contribution. In this scenario, $Y$ will win the Turing award circa 2015

As a person from the future, I can spoil it and let you know that Scenario 1 played out as expected.

Conclusions (Predictions) for XML

They claim that XML will be popular for “on-the-write” data transfer due to it’s abilities to pass through firewalls. XML can be used to transfer data to and from machines, and OR functions can be written to import and export this data. They claim that it will take at least a decade for XML DBMSs to become high performance engines capable of competing with the best of the current RDBMSs. It is more likely that a subset of XML-schema is implemented, which would likely just map to a current RDBMS anyway, making it not very useful. In short, the future for XML DBMSs is very bleak.

XML was sometimes marketed as the solution to the semantic heterogeneity problem. But this is not true, two people can tag the same field as “salary”, but one could be post-tax returns in French Francs and the other pre-tax in USD. The fields are not in any way comparable to each other and should not be stored as the same attribute.

They also make a couple of claims regarding cross-enterprise information sharing, essentially data being shared from different businesses in the same field to an external party. For example, there are hundreds of vacation / airplane ticket booking websites with varying schemas used under the hood but they all communicate with the same airline company to book the ticket. They also make note that Microsoft had initially pushed “OLE-DB” when it perceived a competitive advantage there and killed it off as soon as it didn’t see one there. Similarly Microsoft is pushing hard on XML because it sees a thread from Java and J2EE. The closing note is worth reading:

Less cynically, we claim that technological advances keep changing the rules. For example, it is clear that the micro-sensor technology coming to the market in the next few years will have a huge impact on system software, and we expect DBMSs and their interfaces to be affected in some (yet to be figured out) way.

Hence, we expect a succession of new DBMS standards off into the future. In such an ever changing world, it is crucial that a DBMS be very adaptable, so it can deal with whatever the next “big thing” is. OR DBMSs have that characteristic; native XML DBMSs do not.

Lessons From the Paper

- Lesson 16: Schema-last is a probably a niche market

- Lesson 17: XQuery is pretty much OR SQL with a different syntax

- Lesson 18: XML will not solve the semantic heterogeneity either inside or outside the enterprise.

Full Circle

This paper has surveyed three decades of data model thinking. It is clear that we have come “full circle”. We started off with a complex data model, which was followed by a great debate between a complex model and a much simpler one. The simpler one was shown to be advantageous in terms of understandability and its ability to support data independence.

Then, a substantial collection of additions were proposed, none of which gained substantial market traction, largely because they failed to offer substantial leverage in exchange for the increased complexity. The only ideas that got market traction were user-defined functions and user-defined access methods, and these were performance constructs not data model constructs. The current proposal is now a superset of the union of all previous proposals. I.e. we have navigated a full circle.

The debate between the XML advocates and the relational crowd bears a suspicious resemblance to the first “Great Debate” from a quarter of a century ago. A simple data model is being compared to a complex one. Relational is being compared to “CODASYL II”. The only difference is that “CODASYL II” has a high level query language. Logical data independence will be harder in CODASYL II than in its predecessor, because CODASYL II is even more complex than its predecessor. We can see history repeating itself. If native XML DBMSs gain traction, then customers will have problems with logical data independence and complexity. To avoid repeating history, it is always wise to stand on the shoulders of those who went before, rather than on their feet. As a field, if we don’t start learning something from history, we will be condemned to repeat it yet again.

More abstractly, we see few new data model ideas. Most everything put forward in the last 20 years is a reinvention of something from a quarter century ago. The only concepts noticeably new appear to be:

- Code in the data base (from the OR camp)

- Schema last (from the semi-structured data camp)

Schema last appears to be a niche market, and we don’t see it as any sort of watershed idea. Code in the data base appears to be a really good idea. Moreover, it seems to us that designing a DBMS which made code and data equal class citizens would be a very helpful. If so, then add-ons to DBMSs such as stored procedures, triggers, and alerters would become first class citizens. The OR model got part way there; maybe it is now time to finish that effort.